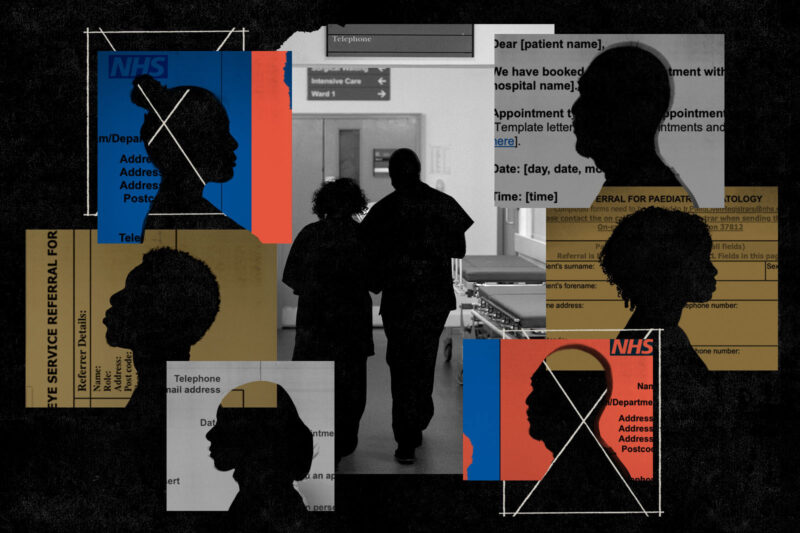

British Muslims and the battle against long Covid

The pandemic has had a disproportionate effect on working-class and ethnic minority communities in the UK. For some, its consequences show no sign of ever going away

Lyth Hishmeh, a British-Palestinian software engineer, had just moved back to Camberley, Surrey, from Jordan to work at a software company when the first wave of Covid-19 struck the UK in early March 2020.

Word of the global pandemic had begun to dominate the news cycle. “The guidance from the World Health Organisation (WHO) was if you’re not above 60, then you’re fine, and it’s funny because a co-worker of mine about my age, we were joking with another co-worker about how we didn’t have to worry about coronavirus,” the 29-year-old recalled.

On 13 March, however, Hishmeh developed a cough that turned into a “flu-like illness”. With no community testing available at the time, it was impossible to determine whether he had coronavirus. Hishmeh was bed-bound for days and took paracetamol for the pain.

Then on 26 March, in a historic televised address, then UK prime minister Boris Johnson ordered the first in an unprecedented series of three national lockdowns. In a desperate attempt to slow the spread of the disease and prevent the NHS from being overwhelmed, Johnson ordered everyone not to leave home unless absolutely necessary.

“No prime minister wants to enact measures like this. I know the damage that this disruption is doing and will do to people’s lives, to their businesses and to their jobs,” Johnson said. “The way ahead is hard, and it is still true that many lives will sadly be lost.”

Hishmeh’s symptoms began to subside around two weeks after he first developed a cough, but his mother and younger brother, whom he lived with, were then also ill, most likely with Covid. Having completed his self-isolation period of 14 days, Hishmeh left the house to purchase groceries, medication and other essentials. Suddenly, his seemingly benign symptoms spiralled. He remembered feeling weak and dizzy. “Suddenly, my arms felt heavy and I couldn’t breathe,” he said. “I had palpitations and the world started spinning. There was a police car passing by, and I remember flagging it and just collapsing against the wall.”

‘I couldn’t pray, I couldn’t do anything, I would call my GP every day, and they would just say, “There’s no evidence that Covid causes any of this. It’s all in your head”.’

Paramedics from Frimley Park Hospital arrived at the scene and conducted an ECG that showed slightly abnormal results. Hishmeh was sent to a local hospital where a consultant performed an ultrasound. He was told that there was nothing wrong with his heart, but that he had remnants of pneumonia in both lungs. “He said, ‘I would say this is the end of it, so you should recover. You should be fine. You’re fit, you’re healthy. You don’t have any comorbidities. You’ve never had any health issues,’” Hishmeh recalled.

But over the next few months, his symptoms, which had now developed into brain fog, unrelenting back pain, delusion and memory loss, worsened, causing him to be almost completely bed-bound. “I couldn’t pray, I couldn’t do anything,” he said. “I would call my GP every day, and they would just say, ‘There’s no evidence that Covid causes any of this. It’s all in your head.’”

Between March 2020 and September 2020, Hishmeh went to A&E some 14 times. Each time, the tests came back normal. “That just drove me even more insane, because everything was normal but I was not feeling normal,” said Hishmeh. “I just wanted to die,” he admitted. “If suicide wasn’t haram in Islam, then I would have probably ended it.”

Over three years later, Hishmeh still suffers from hypersensitivity, chest pain, headaches, eye strain and fatigue, and continues to battle long Covid as he tries to return to normal life.

Long Covid and health inequality

Hishmeh is one of around 2 million people in the UK living with long Covid. Most people who contract coronavirus make a full recovery within 12 weeks. Long Covid, also known as post Covid-19 syndrome, is a condition where symptoms persist for longer than 12 weeks, and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis, according to the NHS.

The most common symptoms are fatigue, shortness of breath, joint or muscle pain, hair loss, loss of smell, dizziness and unusual changes in menstrual cycles. Other symptoms include issues with memory loss and concentration (also known as brain fog), chest pain and rashes, to name but a few.

As coronavirus slowly began to claim thousands of lives in March 2020, the UK government came under fire for describing it as the “great leveller”. But early on, when official data was still nascent, the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on the UK’s working-class and ethnic minority communities was fatally obvious. In April 2020, during the first wave, the first four frontline doctors to die of coronavirus in Britain were all Muslim.

From January 2020 to February 2021, Muslim men and women had higher rates of death involving Covid than those identifying as Christian, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Economic disadvantages, intergenerational living arrangements, pre-existing health conditions and geographical inequalities were thought to be responsible for a large proportion of the deaths. Another significant inequality of long Covid is that it affects women more than men.

Researchers who have looked at the impact of Covid-19 on British Muslims say those conditions played an important role in exposing some people to the virus. “Against this backdrop, significant proportions of the Muslim community also worked in health services as essential workers and faced far greater exposure to the risks of Covid-19 as a result,” said Dr Damien Breen, who co-authored a study for Birmingham City University on the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 and lockdowns on British Muslim communities across Birmingham.

The findings challenged narratives in online and tabloid media that insinuated British Muslims were resistant to following public health guidance and unwilling to engage with testing and vaccinations. “In addition to elevated risks of mortality, where individuals recovered, the effects of long Covid could persist, resulting in increased caring responsibilities for families,” Breen added.

The national picture was just as bleak for minority groups in general. In the first and second wave, from 24 January 2020 to 8 January 2021, people identifying as Muslim, Sikh and Hindu had a higher risk of death from Covid according to ONS data. Bangladeshi, Pakistani, Black African and Black Caribbean males had significantly higher mortality rates than their white counterparts. The same was true for females from the same ethnic groups.

Although the majority of the UK’s 229,000 Covid-19 deaths were among those aged 60 and over, the NHS says there is no firm evidence suggesting that the chances of having long-term symptoms are linked to how ill a person is when they first contract the virus. Even those who experience initially mild symptoms can go on to develop debilitating cases of long Covid.

At the time the first wave gripped the UK, those with long Covid symptoms were left to fend for themselves. But in June 2020, Hishmeh stumbled across a newspaper article about a support group called Long Covid SOS. Now a UK-based charity and campaigning group, it was initially set up by long-term sufferers to highlight the mostly invisible struggles of people left alone to deal with long Covid symptoms, to put pressure on the UK government to recognise their needs and to raise awareness of those with similar symptoms.

“I met more people who were my age who had it, and it started to feel a bit more normal,’” Hishmeh said of Long Covid SOS, whose members he first met through an online forum on the messaging service Slack.

In May 2020, as mounting medical evidence and patient testimony showed some people were struggling to shake off the symptoms of Covid, the NHS set up “post-Covid” rehabilitation and recovery services.

That same month, University College London (UCL) Hospital established one of the UK’s first NHS long Covid clinics and was inundated with referrals from patients who required hospital treatment. Hishmeh has been attending appointments at UCL nearly every month since August 2020 and has received a number of treatments, including blood tests and scans to assess organ damage and the efficacy of medication he has received.

The clinic has helped Hishmeh better understand the long-term effects of his illness. “They’ve listened to patients, they’ve treated a lot of people, and they were the only clinic for a time that were taking people from outside London as well,” he said.

Living with long Covid

Muslims who have been hit by long Covid have described to Hyphen how their symptoms have led to life-changing outcomes. In November 2021, during the second wave of the pandemic, Shabina Malik-Johnson, a civil servant from Alderley Edge in Cheshire, was already taking extra precautions because of underlying health issues. She was among those deemed extremely vulnerable by the government and prioritised for early vaccination in February 2021.

Malik-Johnson, 34, had dreamed of becoming a mother since she was a girl. Her plans were initially delayed by a diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia, a precancerous condition caused by an irregular thickening of the uterine lining. Before contracting coronavirus in 2021, Malik-Johnson had undergone biopsies and progesterone treatment for two years and was finally given the all-clear to safely try for a baby. “I got the go-ahead in October. Then all of a sudden, I was hit by Covid,” she said.

On 27 November 2021, Malik-Johnson and her husband were set to fly to Belgium for a short trip to visit a friend. She took a coronavirus test as a precaution just before departing for the airport. It came back positive. A month later, Malik-Johnson, struggling to get out of bed because of chronic fatigue, was forced to take time off work for several months.

In addition to her full-time job, Malik-Johnson is a team leader for the National Citizen Service, a parish councillor and a stepmother to a pre-teen. Now, she says that long Covid has upended her life. “My life has completely changed,” she said. “I am no longer the person who would take a group of kids hiking for hours on end. I can’t go up the stairs without being out of breath.”

Like Hishmeh, she experienced changes in her physical and mental health, but was initially told there was no certainty that they were consequences of long Covid.

Malik-Johnson has been seeking medical help for her condition since November 2021. Several visits to A&E at Wythenshawe hospital with chest pain and difficulties with her kidneys on a visit to Cambridge eventually revealed that she had scarred lungs and inflamed lymph nodes. “No one knows why that’s happened, or if there’s any link to Covid,” she said.

On one visit to hospital, Malik-Johnson was advised to take paracetamol for chest pain and that it would clear in 12 months. “Nothing went away,” she said. “I can’t go to a supermarket or shop unless there’s a trolley, because I have to have the trolley in front of me, essentially like a walking aid.”

She was eventually referred to a long Covid clinic in May last year by her local hospital. “Not everyone had access to them because they’re only in certain locations, so I was told I was lucky,” Malik-Johnson said. “After one visit, a series of blood tests and ECGs at the clinic, I’ve never heard from them again.”

The uncertainty has also been challenging for Malik-Johnson’s husband, Deej. “He just became my carer because I was incapable of doing anything,” she said.

Malik-Johnson is currently working flexible hours, but has had to take a step back from her other roles. “I’ve been on antidepressants most of this year from January. I just couldn’t take it any more,” she said. “I finally got to the point where my whole old life was just gone. I’ve been pushing and pushing and pushing myself to do things, but I’m in a constant state of exhaustion.”

Malik-Johnson has also had to delay her plans to have a baby. “The thought of walking myself around, let alone carrying a baby… how would I go through labour when I’m feeling this level of exhaustion now?” she added.

Three years since the pandemic first swept across the UK, a clear treatment pathway for long Covid has yet to be determined.

Dr Salman Waqar, a founding member and president of the British Islamic Medical Association, an independent organisation that brings together Muslim healthcare professionals across the UK, says challenges include addressing how the symptoms of long Covid are tackled and how seriously they are taken, especially for British Muslims who are more likely to face stigma and racism in healthcare settings.

“Muslims are likely, as are other ethnic minority communities, to be underdiagnosed and underrepresented when it comes to these conditions,” said Waqar. “We also have to get health professionals to believe us, especially when many of these conditions are non-specific. It can be things like chest pain, things that are synonymous with anxiety or mental health problems. They can be synonymous with many other conditions, which could be minimised because of racial or ethnic and religious biases. People may not get the treatment that they need.”

A life-altering experience

Three years since Hishmeh first became ill, his quality of life has gradually begun to improve. At the worst point of his illness, he lost around eight kilograms in weight. Separate from his treatment at UCL, he volunteered to take part in a study to map how Covid-19 affects the health of six key organs, including the lungs, heart, kidney and liver. He found out he had a mildly impaired cardiac pumping function and a swollen left kidney.

As the youngest person in the Long Covid SOS support group, Hishmeh helped set up a campaign during the early months of the first wave to push for recognition and medical care for long Covid sufferers. In July 2020, the group launched a widely shared video campaign on Twitter, where long Covid sufferers held up placards with their names and the number of days they had struggled with symptoms, and sent letters to the prime minister, the health secretary and MPs.

By August 2020, the group had set up a meeting with Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the WHO, to share their experiences with other sufferers from around the world. In response, the WHO pledged to spread awareness. Hishmeh and other members of Long Covid SOS were eventually invited to join a panel to help draft national guidelines for the management of long-term symptoms of long Covid for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

After having his symptoms dismissed by his own GP at one point, Hishmeh feels vindicated: he is finally being taken seriously. “At the time I was feeling at my lowest, to be able to have taken part in something that GPs all over the UK would go over when treating patients with long Covid, it was quite a confidence boost,” he said.

After a two-year professional break, Hishmeh is now back at his job and working variable hours. He still struggles to walk long distances and his long Covid symptoms flare up when he gets a cold or when winter approaches. While he has had to take a step back from campaigning, he believes he has played his part. “The message is out,” he said. “People are aware of the symptoms. I feel like I’ve done everything I can.”

Newsletter

Newsletter