Mariam Ansar Q&A: ‘My novel is a love letter to the north’

The Bradford-born writer and secondary school English teacher says her teaching career has been a big influence on her work. Photograph courtesy of Mariam Ansar/Robin Christian

The young adult novelist on becoming a published author and the north-south divide

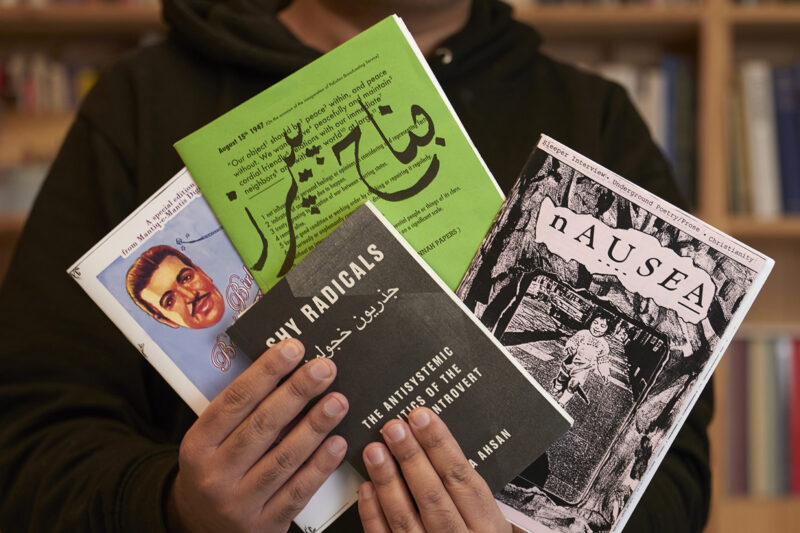

Mariam Ansar, 27, is a Bradford-born writer and secondary school English teacher. Her debut novel, Good For Nothing, was published by Penguin Random House in March 2023. The young adult story follows three teenagers, Amir, Eman and Kemi, living in a divided northern town.

Amir is still seeking answers to his brother’s death two-and-a-half years earlier, while Kemi and Eman are on their own journeys of self-discovery. The characters come from different family backgrounds, and their lives come together one summer after a graffiti incident lands them with a community service order.

Here, Ansar talks about how her teaching career has influenced her work and how she represents northern communities through her writing.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How would you describe Good For Nothing?

I see it as a love letter to the northern community, focusing on the lives of people that are often left out of dominant narratives. In the UK, we have such a southern-based focus on development and progress. There are young voices who are quite angry about the fact that they’re not really included. Writing this book felt like a reclaiming of not just forgotten areas but also forgotten emotions, and using those emotions to shed a light on important issues.

How do you hope your writing will dispel stereotypes about the north and northern Muslims?

I’m not actively trying to teach anyone anything or trying to dispel a stereotype. I’m letting people be themselves. I work as a teacher in quite a deprived area. There’s a defiant “it is what it is” mentality here and I respect that. There’s this idea that we have to be palatable and soft and that we have to do all these things to be seen as exceptional. My three main characters are not the perfect representation of being Muslim or a person of colour. That was very intentional.

Why did you choose to set your book in a fictional town and not your home town of Bradford and what, if any, elements of Bradford did you use to build that world?

I think for a young adult audience and for communities that are often overlooked, I wanted there to be a place that they could recognise, even if it didn’t have a name like Doncaster or Huddersfield. A friend of mine from east London read the book and said it felt like I was talking about her home. I think it’s because we have so much in common in that way — that kind of deprivation or feeling like you’re forgotten. I wanted people from every ethnicity and every background, whether you’re northern or southern, to recognise that this geography that I’m making up is actually your geography too. If you’re looking closely, you can see that it’s definitely Bradford, but I like the ambiguity in keeping it concealed.

How has your teaching career influenced your writing?

With teaching, it’s a dynamic job and you’re seeing young people come in and live their lives, and getting to know themselves. There is something very earnest and sweet about it, even in the difficult moments. I think it’s inevitable that I’m going to take from some of their experiences.

Were you worried about your students’ opinion of your writing?

I wasn’t worried. It was really personally fulfilling to hear how excited they were because they were reading names that fitted their vernacular so well. I thought a lot about code switching and how there’s this pressure for people from racialised backgrounds to speak a certain way to be respected. I want there to be more space for boys and girls to talk in the way that they think. I intentionally wrote the book in a way that imitates the way they talk. Hearing my students who sounded like my characters reading the book was so nice and was really enjoyable for them too.

What kind of challenges did you face within the publishing industry and do you have any advice for Muslim writers on how to overcome them?

I think some of the challenges that came for me were people misunderstanding what I was trying to do. As the writer, you’re going to have this intense attachment to what you’re trying to do. Someone in publishing is thinking about how they’re going to make your book marketable. It’s important for young writers to know you can actually say no to suggestions. Don’t be afraid to put your foot down. Make sure you have a good relationship with your agent or somebody who can fight those fights for you.

What story about your community would you most like to see in literature?

I’m so inspired by young South Asian girls who have that rebellious streak and who are defiant of the pressure of having to look and be a certain way. I think there are quite a lot of narratives that aren’t told and I’m hopeful that we can make space to allow us to be weirder and fulfil things that don’t fit the narrative of what’s expected of us. I just want to make really weird books.

Newsletter

Newsletter