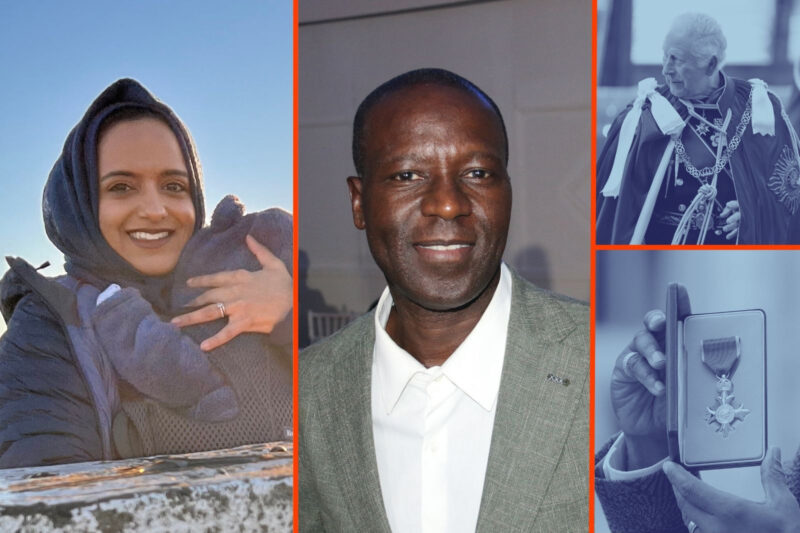

‘I used the Globe to start the conversation about Shakespeare and race’: Farah Karim-Cooper Q&A

Photograph courtesy of Shakespeare’s Globe/Sarah Lee

The academic and author talks about the power of theatre, the culture wars, and how the comedian and actor Robin Williams led to her love of Shakespeare

–

Professor Farah Karim-Cooper is a widely acclaimed expert on William Shakespeare and has worked at the Globe Theatre for 18 years, the last three as co-director of education. She has also served as the President of the American Shakespeare Association.

In 2018, she curated the first Shakespeare and Race Festival at the Globe, facing down a backlash for her work in examining the racism in Shakepeare’s plays while maintaining their enduring relevance. Her most recent book, The Great White Bard: Shakespeare and Race Then and Now, has just been published.

This article has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you tell me how you developed your interest in Shakespeare?

I finished high school in 1989 and was trying to figure out what I wanted to do. Then I discovered the movie Dead Poets Society and realised that I wanted to be an English teacher. I decided to major in English at university and had this amazing Shakespeare class with a fantastic professor. I thought that Shakespeare’s work was immense and powerful, and it spoke to me personally. I wrote a bit about Romeo and Juliet when I was in high school, but it really wasn’t until I was in college that I realised how powerful the work actually is. So, really, I came to it through Robin Williams.

And from there you went into academia?

I wanted to pursue advanced study of Shakespeare. I knew I wanted to do a master’s programme and to go on to a PhD. So when I was doing my bachelor’s degree, I knew that this wasn’t the end and that I was going to be a professor.

What did you decide to focus your academic work on?

I decided to come to England to do my master’s degree, because I thought, “Well, he’s an English writer, so I want to go study in England.” I was looking for a Shakespeare programme in London, and there weren’t any at the time. The closest thing I could find was a master’s at Royal Holloway in John Milton, who was a 17th-century poet. It was very difficult, very challenging and wasn’t exactly what I wanted, but I did manage to write a dissertation about Shakespeare and the influence he had on Milton. That led me to my PhD thesis, the research that I wanted to do, which was looking at deception and beauty and women’s history and the representation of artificial beauty on stage. That led me to research into cosmetics in Shakespeare’s time, which nobody had really written about before, and that was the first book I published.

How did you go from academic research to co-director of education at the Globe?

I wanted to teach at a university but, in this country, if you specialise in English literature, it’s really hard to find a permanent job. I did a little bit of adjunct teaching here and there and then, finally, in 2004, I noticed that there was a lecturing job that came up with the Globe, because the education department had created a brand new master’s degree at King’s College London. Then I just worked my way up to head of research, which I did for 15 or so years. For the last three years, I’ve been director of education, responsible for our higher education and our research programme.

Can you tell me about your work on Shakespeare and race?

There’s this big conference called the Shakespeare Association of America, which is the biggest scholarly organisation in the world dealing with Shakespeare. Eventually, I was elected to the board and became a trustee. We were doing some work on racial diversity in the field and I realised it was just as bad, if not worse, here in the UK.

Some people think of the Globe as this sort of mothership of all things Shakespeare, so I just decided to exploit that to get this conversation going. I curated the Shakespeare and Race Festival in 2018. We platformed scholars and theatre artists of colour, getting them to account for their own experiences: the scholars to talk about their research, the artists to talk about what it feels like to be an artist of colour in a rehearsal room, which is white-dominated. Most theatres in this country are white spaces.

And this is also the theme of your most recent book, The Great White Bard.

I wanted to tell people about the difficulties that I have as a woman of colour with Shakespeare. His plays are immeasurably powerful, but there’s stuff in there that’s uncomfortable and harmful, and we have to talk about it. That’s what I wanted to share with the general reader how Shakespeare can be reclaimed for the 21st century. We don’t have to cancel him just because there’s misogyny and anti-Black racism in some of his plays. But we also shouldn’t revere him without being alert to those things. The colour-blind approach to Shakespeare is harmful. One of the main points of the book is to demonstrate how we can navigate these plays by seeing these things, but it doesn’t have to hurt Shakespeare and he’ll be fine by the end of it.

Do you feel Shakespeare’s works and body of work has particular resonance for Muslims?

Entirely. In that time period, there was a lot of foundational racism that started, whether it’s antisemitism or Islamophobia. Shakespeare’s contemporaries are writing “Turk plays” and the representation of Muslim figures at this time was not good. What was interesting is that Shakespeare is one playwright who doesn’t write a Turk play. He has Turks in Othello, but these are powerful people who the Venetians are at war with. They don’t ever show up on stage, they’re just a looming threat. Some people have argued that Othello is based on a Moroccan ambassador. So there’s a whole strand of scholarship looking at his religious background and history.

Some people have suggested that Shakespeare was not alert to Islamophobic representation or antisemitism or anti-Black racism, but that feels uninspiring, myopic and closed-down because he is talking about these things. This is a world in which there are contemporaries of Shakespeare who are travelling out into different parts of the world and trading and developing relationships, beginning the roots of colonisation.

Your work has attracted criticism and attack from some other academics and people who oppose decolonising western culture. How has that been for you?

As a scholar of colour, you are automatically given less weight in conversations about Shakespeare in the public domain. That is the big risk that I’m taking by publishing this book for a general readership because there are no other women of colour, public intellectuals when it comes to Shakespeare. When we announced the antiracist Shakespeare webinars at the Globe, it made everybody on the other side of the culture war furious, and we were attacked on Twitter. I had to lock my account. I was written about on Breitbart and GB News had stuff to say about it. It was just mean and nasty, and, at times, completely ignorant.

What was the last play you saw?

The last piece of theatre I saw was Hamnet at the Royal Shakespeare Company, which is an adaptation of Maggie O’Farrell’s book about the death of Shakespeare’s son. It’s a fictional account of how he might have died, and it’s the plague that kills him, but the focus of the story is very much on Shakespeare’s wife. The amazing playwright Lolita Chakrabarti wrote the adaptation and I worked with her on it, helping her with the history and the research.

What is your favourite Shakespeare play?

My favourite play is Titus Andronicus, Shakespeare’s first tragedy and the first revenge tragedy. It’s full of blood and gore, but that’s not why I love it. I just find it really exciting and thrilling. He explores so many things there that he takes into more depth elsewhere later in his career. Here he is really unpacking human nature and empire and blackness and misogyny. He creates this incredible story, which is full of the horrifying things that human beings do to each other and it makes you look at human nature and you sort of almost feel like “Why are we even here? We’re so horrible.” But then you find redemptive moments in the play and you find love at the heart of it. It’s extraordinary.

Newsletter

Newsletter