The mystery of the first English Qur’an

Questions about the identity of the translator and what their motivations were still remain, 370 years after publication

–

As years go, 1649 was a challenging one to publish a book. England was seven years into a Civil War between royalists and parliamentarians. In January of 1649, King Charles I was tried and executed for treason, the monarchy was abolished and the country became a republic, under the leadership of Oliver Cromwell. Yet, this was when the Qur’an first became available in the English language.

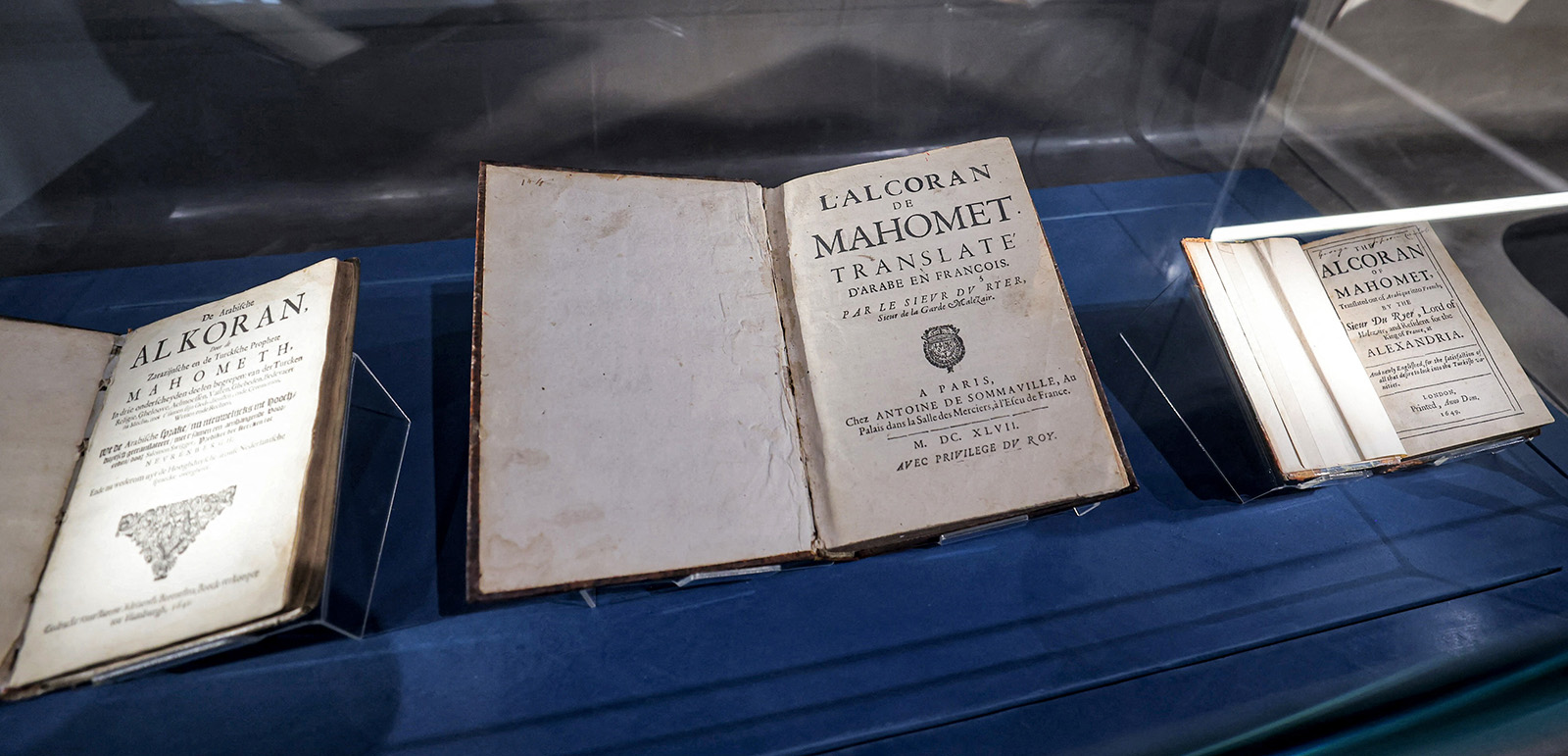

The story of the Alcoran of Mahomet is shrouded in intrigue involving a web of royalist intellectuals, arrests and attempts to ban its publication. The most enduring mystery of all, however, is who translated it and why. Rather than using the original Arabic as the source, it was adapted from a French-language version by the diplomat and trader Sieur Du Ryer. The French-language version had been published two years earlier and was, itself, the first western translation of the Qur’an to be produced since mediaeval scholars transcribed the holy book in Latin.

What is certain is that the Alcoran appeared a time when European interest in the Muslim world was rising. According to Professor Nabil Matar from the University of Minnesota, this was less motivated by a search for spiritual enrichment than it was by the pursuit of wealth.

“France, England, and Holland — all three saw tremendous advantage in trade with the Levant, with the Ottoman Empire, and part of trade is to know who your counterpart is religiously, culturally and socially,” he said.

The Alcoran’s planned publication caused a panic in the English parliament

In the French version, Du Ryer referred to the works of well-known Turkish and Arab scholars in margin notes. Most of these insights were retained in the English adaptation. Despite attempts by the authorities in Roman Catholic France to suppress its publication, the book became an under-the-counter success. There was every reason to believe that the English version would be similarly well received.

The Alcoran’s planned publication caused a panic in the English parliament. A former soldier named Colonel Anthony Weldon brought a petition against publication to parliament and persuaded MPs to send constables with him to seize the print run and arrest those involved. Weldon was a disillusioned soldier who complained he had made many sacrifices for the new British government, so the Alcoran gave him the opportunity to both get parliament’s attention and to play the hero again.

The printer, John Stephenson, was interrogated about who was behind the book and what their motivations for publishing it were. Stephenson said he had got the manuscript from a man named Thomas Ross. Ross was then brought in for questioning by the government, and released with a warning “not to meddle more with things of that nature.”

A month later, the investigation was dropped and the Alcoran was published, although the publisher and printer — probably wisely — did not credit themselves in the text. “There was a sort of aura of sort of wrongness and possible blasphemy surrounding it in people’s minds,” explained Professor Noel Malcolm, Senior Research Fellow in History at the University of Oxford.

The version that reached English readers featured several additions, including an anonymous translators’ note, an uncredited essay on the life of prophet Mohammed and a post-script essay written by Alexander Ross, a former chaplain to the late King and Thomas Ross’s uncle.

The translation of the Alcoran into English has long been attributed to Alexander Ross, but experts have begun to question whether it could have been someone else. Malcolm is one of them.

“It’s clear Alexander Ross had been pulled in at the last minute to do a job of justification,” Malcolm said, explaining that as a credible public intellectual, Ross’s words were there to reassure the authorities that the Alcoran was safe to publish and would not entice English people away from Christianity.

Malcolm also pointed out that later work on Islam by Alexander Ross contradicts the essay on the life of Mohammed included in the Alcoran. He does not believe that Thomas Ross was responsible either, highlighting the fact that he was known for his translations from Latin, not French.

Matar maintains that Alexander Ross was the man behind the English Alcoran, but acknowledges that the credit is probably “up for grabs”. Alexander was, in his view, doing it in order to argue against the teachings of Islam.

“His point of view was that we needed to translate this because we needed to know the errors in order to refute them,” said Matar.

To make matters even more confusing, Malcolm believes that a man named Hugh Ross, a more distant relative of Alexander and Thomas, was the real translator. He had worked in French law courts on behalf of English traders, so was fluent in the language. He was also in financial trouble, so needed side-hustles such as writing and translation.

The truth of the matter, however, is that we can never know for sure. Thomas Ross, who went on to be involved in various plots and uprisings against the English Republic and in favour of the exiled son of the executed King Charles, died in 1675. Alexander Ross worked as a vicar on the Isle of Wight until his death in 1654. Hugh Ross died in June 1649 and his story has largely been lost to history.

The influence of the Alcoran lived on far beyond the Rosses and the English Republic. It was reprinted in 1688, but by that point Europe’s focus was on trade with the Americas, making understanding of the Islamic world less of a priority for many. However, it laid the ground for another, better-known translation of the Qur’an to be published 100 years later — this time directly from the Arabic — by George Sale, an Orientalist scholar.

One lesson to take away from the saga is how, even 400 years ago, when there were only a handful of Muslims in England, a mix of fascination and fear of Islam was being used to make money and boost the flagging careers of politicians and public figures.

Newsletter

Newsletter