Spain prepares to pass the first menstrual leave law in Europe — but there is still work to be done

A new bill aims to give extra paid leave for menstrual and period pains. Some Muslim women, however, fear it could lead to further marginalisation in the workplace.

–

In a European first, Spain is to pass a landmark menstrual leave law, mandating that workers suffering from severe period pain will be entitled to an extra three days of sick leave per month.

The draft bill — which forms part of a broad package on reproductive rights that also aim to improve access to abortion, abolish VAT on many feminine hygiene products and provide free tampons and sanitary towelr in schools, prisons and other public centres — could be passed later this year o early next by parliament.

According to the Spanish Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, around a third of women who menstruate suffer from painful periods. According to the bill, if they wish to take menstrual leave, they must undergo a medical examination each month. If the results recommend medical leave, those affected will receive full state-funded sick pay without any impact on their annual sick leave allowance.

Yet, while legislation has generally been well-received by trades unions, some Muslim women say they will be reluctant to take menstrual leave for fear of being further marginalised in the workplace.

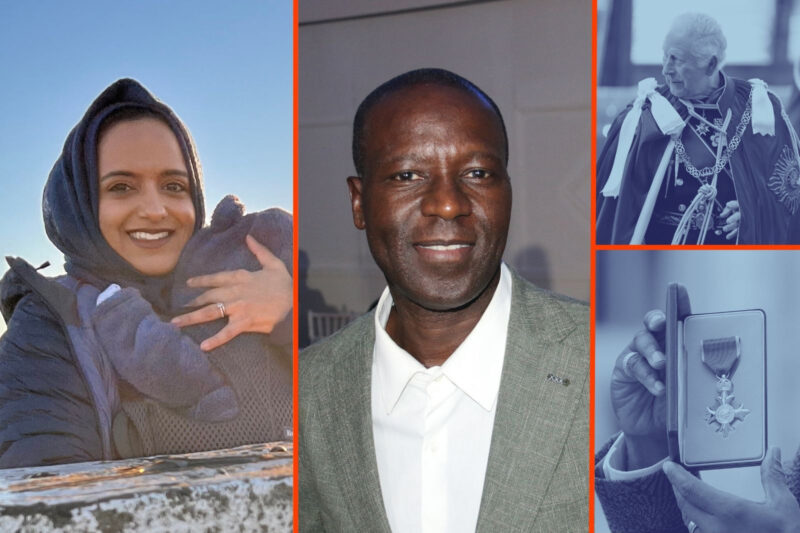

Hayar Boudzaz is a nursing assistant in a hospital traumatology department in Madrid. On her day off, she met me in her neighbourhood of Tetuán, where she explained what it’s like working in A&E as a sufferer of dysmenorrhea, or painful periods.

“During the first three days of my period, my blood pressure goes down, I feel faint, and it’s very painful,’ she said. “All I want is to be in bed in a foetal position, so you can imagine it’s very hard trying to work like this.”

Like many women, however, Boudzaz, who has worked at the hospital since 2017, has normalised working with period pain since the beginning of her medical career. As the first person in the hospital to work while wearing a hijab, she feared that if she did anything wrong, her colleagues would start talking about her culture and religion.

“I was new, I didn’t want to lose my job, and I was aware that my colleagues already had an opinion of me before they even knew me. They’d say, ‘You’re a Muslim but you’re friendly, you’re a Muslim but you’re funny, you’re a Muslim but you’re really sociable and you work well.’”

Spain will not be the first country to introduce a menstrual leave law. In 1947, Japan granted women leave when their working conditions or workplaces did not support their ability to work while on their period. While no medical examination is required, fewer than 10% of Japanese women take this leave today for fear of workplace stigmatisation.

The most recent country to propose a menstrual policy is Australia, which could grant employees one day per month, or 12 days’ annual paid leave. Sufferers of dysmenorrhea might soon be able to either take breaks at work, work from home, or take one full day’s paid leave when needed and, as in Japan, a medical certificate is not required.

In a cafe on the other side of Madrid, in the multicultural neighbourhood of Lavapiés, I spoke to Fátima Bourhim, a physical therapist specialising in women’s health.

“We live in a patriarchal system,” she said. “As women, we already have a lot of workplace fears. Add to that being from a lower social class, being an immigrant, being racialised, or being a Muslim. In the workplace, any one or a combination of these characteristics can result in you being viewed as weaker or less productive.”

Amal Hussein Ismail, an activist for the prevention of female genital mutilation, agrees. She explained that feminism in Spain doesn’t generally take immigrant women into account.

“I know many people who have immigrant backgrounds, like me,” she said. “Getting a contract for a full-time job is already very hard, so taking leave every month simply isn’t an option.”

As Ismail explains, many immigrant women are incredibly vulnerable to labour exploitation. “They work in houses for hours, seven days, with no time to rest,” she said. “These people can’t access this leave. It’s not something that will even enter their mind as an option.”

In parliament, I met Isabel Franco, an MP for Seville from the anti-austerity coalition Unidas Podemos (United We Can). As a specialist in workers’ rights, she was quick to express a concern familiar to many women: “If a woman is in pain, she is seen to be of less value. If a woman becomes a mother, she works less and is therefore seen to be of less value.”

Bourhim is worried about the new menstrual law since she feels her employment situation is already precarious.

“I found it hard to get a job because of my hijabi identity,” she explained.

After a successful interview for a job in physical therapy, she was effectively told that unless she removed her hijab, she had to turn down the role and that it was her choice and her problem. “On top of this,” said Bourhim, “how can I show my pain? In the end, perhaps it’s better to just keep working in pain.”

Boudzaz said that should she want to take menstrual sick leave, her managers and colleagues may not believe that she’s unable to work. “When I had tendonitis, for example, they didn’t believe me that I was in pain. No one helped me. No one had my back.”

She is also concerned that her male employer will be unsympathetic to her medical needs.: “I wouldn’t want to tell my boss I was having my period because maybe he won’t think it’s a genuine problem. But if we had a female intermediary who could communicate this, who might be more likely to believe me, it would be better.”

Empathy and understanding are vital factors in bringing the new legislation to workplaces, especially for women for whom menstruation is a taboo. Bourhim explained that during Ramadan, she used to tell her family that she couldn’t come and pray. Now, she said, “I’m more honest but, culturally speaking, there is still a taboo. Religion and culture overlap.”

Although the announcement of Spain’s new menstrual leave bill demonstrates that times are changing, Ismail feels that workplace training around menstruation will be vital for its success.

“We need workshops in primary schools, high schools, universities and the workplace,” she said. “The law could open the possibility of getting funds to support this training too.”

Following the bill’s announcement, however, Ismail told me that she had witnessed a sudden surge in conversations between women talking about their periods: “For the many girls and women who live and work with chronic pain, it’s started a public debate and will open people’s minds.”

Though there are still many concerns to address before the menstrual leave law officially rolls out, the Muslim women I spoke to all agree that the announcement of the draft bill has already prompted a nationwide destigmatisation of menstruation.

“The day the law was announced was an amazing day,” said Ismail. “I imagine, even further into the future, it will do great things for society.”

Newsletter

Newsletter