The hero and the traitor: A tale of two brothers in WWI

How two siblings took opposite sides during the First World War, with one defecting to the Germans and the other awarded a Victoria Cross.

–

The leafy Tirah valley looked even greener in the monsoon rains. Tucked away in the mountainous region between Afghanistan and north-west India — now Pakistan — the snowbound ridges of the Safed Koh range glistened in the morning sunshine.

Meanwhile, in the village of Kharkay, a family of nine were saying goodbye to two of their own. In August 1914, just after the outbreak of the First World War, two sons of Muhammad Ameer Khan received their call to join the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and fight in Europe. They were proud Pashtuns, a tribe that provided a rich source of recruitment for the British Indian Army.

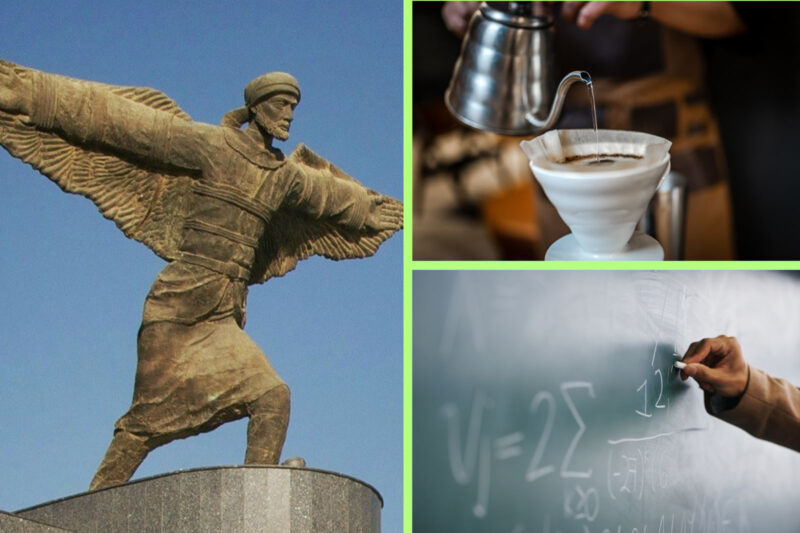

Mir Dast was a jemadar (or lieutenant) in the 55th Coke’s Rifles infantry regiment, which consisted of Muslim, Sikh and Dogra soldiers. Born in 1874, the 38-year-old was a veteran of several British campaigns in Afghanistan and the North West Frontier, where he had risen through the ranks. In 1908 he fought in a British expedition to subdue Mohmand rebels in Afghanistan and was awarded the Indian Order of Merit, the highest military honour at the time.

His brother, Mir Mast, was two years younger and a Jemadar in the 58th Vaughan Rifles. On that August day, they set off for the Western Front to serve in a war thousands of miles away. Mir Mast was dispatched to France, while Mir Dast was sent to Belgium. It was not long before they were both in the trenches, locked in a conflict the likes of which the world had never seen.

They were not alone. Of the 1.3 million Indians who volunteered for the war effort, nearly 400,000 were Muslim. Many of them came from the regions of Punjab and north-west India and joined the Allies in France, Belgium, Gallipoli, Mesopotamia, Egypt and Persia.

Artillery shells ripped through the hopelessly inadequate British forces in Belgium. The cold and damp seeped through the soldiers’ bones. The initial enthusiasm of the troops gave way to despondency as they watched the bodies pile up. Yet, the Indian Corps struggled through, holding the British line at Ypres and preventing the Germans from accessing the sea.

The conflict soon escalated. In March 1915, the British army prepared for its first major offensive against the Germans in Neuve Chapelle in northern France.

Both brothers fought at Neuve Chapelle. Yet as Mir Dast took his position in the trench, Mir Mast had other ideas. A proud Muslim, and a supporter of the Ottoman Empire and the Caliphate, he had been torn by his loyalties when Turkey entered the war on the side of Germany.

The six months of war had exhausted him, and all he wanted to do was go home. On the chilly night of 2 March, a few days before the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, Mir Mast climbed out of his trench along with 14 other Afridis and crossed over to the Germans. Only a few days earlier, he had been awarded the Indian Distinguished Service Medal. By the time the honour was published in the London Gazette on 10 March, he was with the Germans.

Mir Mast was taken to Lille, where he was interrogated. A secret German report from 7 March showed that he drew a map for the Germans pointing out the number and position of Indian and British troops along the Khyber Pass, a crucial connection between India and Afghanistan.

Mir Mast and the other defectors were then transported to the Half Moon Camp for prisoners of war in Zossen, outside Berlin. The camp, which had a purpose-built mosque, was the base for a grand German plan to recruit Muslims for a jihadi war against the Allies. The recruits would be plucked from the Indian and African Muslims in the camp.

The Germans intended to lead a delegation, including Mir Mast, across Asia to Afghanistan hoping they could persuade the Emir of Afghanistan to switch sides and join forces against the Allies. Mir Mast was said to have been decorated with an Iron Cross by German Kaiser Wilhelm II. Dressed in Turkish military attire and abandoning his traditional kullah headgear for a fez, he prepared to accompany the small Turko-German expedition to Afghanistan.

For his bravery at the second Battle of Ypres, Mir Dast was awarded the Victoria Cross

The group first set out for Istanbul, and then towards Baghdad and Persia. They crossed the salt deserts and mountains of Persia before finally arriving in the rocky landscape of Afghanistan. More than half of the group had died of exhaustion and disease. In May 1915, Mir Mast led his delegation to Kabul for an audience with the emir. However, the emir would not be swayed and preferred to remain a British ally.

It is unlikely that Mir Mast cared too much about the failure of the mission. His sole purpose had been to get back home and, in June 1915, he was back in his village of Kharkay.

Mir Mast’s trench notebook lies in the National Archives in Delhi. It provides a valuable glimpse into the mindset of a man who started out as a military hero, but then decided to take his own path. His words paint a picture of a dejected and lonely man, desperately trying to cope with life in extremely challenging circumstances.

The news of Mir Mast’s defection could not have been easy for Mir Dast. He vowed that in the next battle he would make up for any family disgrace. In April 1915, the Lahore Division marched north to Ypres in Belgium. The situation was grim: on the evening of 22 April, the Germans had launched their first gas attack. Thick smoke suffocated the unprepared French colonials. The dead lay everywhere.

On 26 April, the Lahore Division was ordered to counterattack. The Germans launched a second gas attack. While the soldiers of the Lahore Division had no gas masks, they had dipped their turbans in chloride of lime, a widely employed antiseptic solution, and tied them over their mouths. Others had urinated on them and wrapped them around their faces. The toxic fumes made Mir Dast pass out near Ypres.

When he eventually recovered, he rallied a small group of survivors. He held on until nightfall, rescuing the men and taking them to shelter. After dark, he went out to the battlefield again and carried back eight injured British and Indian officers. He was then shot in the hand.

For his bravery at the second Battle of Ypres, Mir Dast was awarded the Victoria Cross. He was taken to England to recover at the Brighton Pavilion, which had been converted into a hospital for wounded Indian soldiers.

On 25 August 1915, King George V presented Mir Dast with the medal and asked him if he would like to make a request. Mir Dast asked that when a man was injured, he should not be sent back to the trenches. He said he spoke for all Indian soldiers, who feared that unless they lost an eye or a leg, they would never see their homeland again. His request was never granted.

Mir Dast never fully recovered from the gassing. He wrote to a friend on 12 July 1915, saying he could no longer move his fingers. “The Victoria Cross is a very fine thing, but this gas gives me no rest. It has done for me,” he said.

Newsletter

Newsletter