Ignored and dismissed: the mental health crisis among young British Muslims

Faced with a lack of understanding both at community level and within the health service, thousands of vulnerable people are going untreated

–

As years go, 2017 is one I’d rather forget — but I can’t. I was 18 years old, had just finished my A-levels and was looking forward to a long summer holiday, before leaving my home in Luton and heading to Warwick University to study for a degree in history and politics.

Those plans began to change when I started to suffer from insomnia.

At first, I found it difficult to switch off and couldn’t understand why. Rather than fight a losing battle, I accepted my feelings as normal and sometimes went two days without sleep. At the same time, I remained preoccupied with current affairs. Back then, the UK had voted to leave the European Union and Donald Trump had just become US president. Far-right politics had entered the mainstream and record numbers of Islamophobic attacks had been reported in the UK. Those facts played a large part in keeping me awake at night.

On 19 June 2017 — which fell in the month of Ramadan — a right-wing extremist drove a van into a crowd of worshippers gathered outside the Muslim Welfare House in Finsbury Park, north London, killing a 51-year-old husband and grandfather named Makram Ali and injuring 12 other people. That same day, my sister had been racially abused by a man on her train commute home from university in London. Two days later, cousins Jameel Muhktar and Resham Khan were attacked with acid while sitting in a car in Newham, east London. Their injuries were described as “life-changing”.

A few weeks later, I attended a vigil in solidarity with victims of anti-Muslim hate crime in Newham, where I spoke about my fear of Islamophobia and its violent consequences. But what started as a pressing and legitimate concern began to morph into paranoia, exacerbated by my lack of sleep.

The thing about psychosis is that it creeps up on you. Initially, I saw my preoccupation with rising racial and religious prejudice as a rational response to a growing threat and tried to get on with my life. That quickly became less and less manageable. Try as I might, I couldn’t stop my mind whirring. Eventually, my paranoia peaked and I began to hallucinate. My family could see me deteriorating before their eyes. Then, in July, I experienced a full-blown psychotic episode. My parents contacted emergency services and were told that I required urgent inpatient treatment.

That’s how I ended up spending those long-anticipated summer months in hospital, sectioned under the 1983 Mental Health Act.

While I was lucky that my family had reached out for help and gained access to the care I needed, that was not the end of the problem. A lack of beds in Luton meant that I was forced to move to a hospital 35 miles away, in east London. I was the youngest patient on the ward, extremely unwell, far from home and in an unfamiliar environment. Much of my time there remains a blur.

I remember being required to take a variety of antipsychotic medications at intervals throughout the day, but not much else. One thing I do recall clearly, though, is the Islamophobic abuse I was subjected to on the ward by other patients — many of whom were also extremely sick. My complaints were often dismissed by the hospital staff as a symptom of my paranoia and no action was taken.

On one occasion, I was overheard chatting with a fellow Muslim patient about prayer as a source of healing. Another patient branded us extremists and spread rumours that we had been radicalised. Soon, others were accusing us of being terrorists. The very last thing I needed at this point was to be in a place where I encountered the exact thing that I had been so worried about. The inaction of staff only heightened my paranoia. Fights between patients were also a daily occurrence, the threat of violence hanging heavy in the air. To make matters worse, I was never really updated about my progress, which made it feel like there was no end in sight. At times I thought I’d be stuck in that place forever.

It turned out that I spent two-and-a half-months there. I wasn’t well when I was released, a few weeks before my university term began, but I left knowing that other patients were in much worse states than me and needed the bed I had occupied. Throughout my time under section and in the weeks after my discharge, my family rallied around, regularly checking in with me and ensuring I was taking my medication on time. Many people on my ward had no such support. I was aware that I was one of the more fortunate ones, but still felt any meaningful recovery was far beyond my reach.

A doctor advised me that it was too soon for me to go to university, but I knew that the consequences of spending a year at home doing nothing would be much worse than moving ahead with my plans. My first year at Warwick was incredibly difficult. The medication I was on left me exhausted. Being a British Pakistani from a working-class background, I would have felt out of place there anyway, but my mental health difficulties compounded those feelings. I came very close to dropping out several times.

One of the main things that stopped me was the fact that, throughout my time there, I had access to an NHS mental health social worker. From our weekly meetings, I learned how to identify early-warning signs and benefited from occupational therapy sessions. I also received guidance on how to manage stress and anxiety and, over time, learned how to control my thoughts better.

It took me a while to settle into student life, but I made some good friends and came to really enjoy my course. I got involved in student societies, serving as events officer of the anti-racism society and ethnic minorities officer in my final year. For a long time, I had withdrawn from the things I was passionate about, but taking on these roles was fulfilling and provided a welcome boost to my confidence.

Five years on, my mental health has never been better. The tools and techniques I acquired from my support worker have been vital in aiding my recovery and I remain conscious that I need to take ongoing care of myself. For me, recovery isn’t something that happens at a fixed point in time but a lifelong undertaking — one that I am getting better at every day. That, however, is just my story. For many more young Muslims, the reality is even more challenging.

Yusuf, a 23-year-old British Pakistani from Luton, has been struggling with depression and social anxiety since 2017. “In my experience, mental health issues in the Muslim community don’t even exist,” he said. “Either I’m told I just need to pray and I’ll instantly get better, or I’m depicted as bored and attention-seeking.”

Yusuf’s symptoms are so severe that they affect his eating, sleep, studies and social life. He believes that a longstanding stigma around mental health in the Muslim community has played a significant role in worsening his condition.

He is not alone. Several young British Muslims who spoke to me for this article explained that older generations often tend to see mental health problems as a failure of faith. This view, they explained, can be found at the root of a range of negative responses, from feelings of shame to denials that such conditions even exist. These positions can often be linked to traditional ideas of masculinity, family honour and self-sufficiency, which cast psychological difficulties as a sign of weakness. While this is gradually changing — as young Muslims, like their non-Muslim peers, become more comfortable discussing their emotional and mental wellbeing — such attitudes present significant obstacles to many people who need help.

For Yusuf, the only way to dismantle this stigma is to educate people and help them understand that mental health problems are real and nothing to be ashamed of. According to the national charity Mind, one in four people in England will experience mental health difficulties every year.

“Going to the doctors and getting medication and therapy is vital,” he said. “The first step to fixing a problem is acknowledging that it’s there in the first place. If I had a broken leg, I wouldn’t just pray that I’m going to get better. I’d go to the hospital and have an operation.”

According to a 2021 report by the Better Community Business Network and the University of East London, mental health issues such as anxiety, depression and stress are widespread among young Muslims in the UK. The document is based on a survey of 729 young Muslims contacted by a number of charitable and community organisations, including mental health campaign groups. It states that 64% of respondents said they have had suicidal thoughts and that 70% of those who reported mental health struggles say they have also experienced Islamophobia.

Ibrahim is a British Somali Muslim and community activist from Liverpool. He told me that mental health is largely unspoken of in his community and something that can “bring peril to the family name”. Accordingly, people are often reluctant to seek medical help from doctors and social workers and have a tendency to turn to religion and Islamic institutions for support.

“For many Muslims, mosques are more than just a place of worship,” Ibrahim said. As such, he believes that it is vital for imams and community leaders to receive practical and up-to-date mental health training.

“Mosques must review their structures, practices and engagement strategies in relation to mental health,” he said. “This is where we are lacking and could do with a major boost.”

The widespread reluctance within Muslim communities to discuss mental health issues is not a historical given. The importance of mental wellbeing actually has deep roots in Islamic tradition. As far back as the 9th century, the Persian scholar Muhammad Ibn Zakariya al-Razi pioneered the treatment of mental illness, writing the book Al-Tibb al Ruhani (The Spiritual Physick). In it he promoted evidence-based perspectives, classified a number of psychiatric disorders and promoted the use of something remarkably similar to cognitive psychotherapy. Razi was also instrumental in establishing psychiatric wards in Baghdad, the first of their kind in the world.

Social stigma is not the only problem that British Muslims face when trying to access care. The systemic issues of an understaffed and under-resourced National Health Service, which affect all sections of society, have also not helped. According to a report published by the Royal College of Psychiatrists in October 2020, one in four people seeking mental health support have to wait at least three months to start NHS treatment. In some cases, that delay can be as long as four years.

As Yusuf explained: “I went to A&E really struggling with severe depression and not knowing what to do. I waited two hours in the waiting room for an appointment that lasted a few minutes, where I was told to take paracetamol and I would be fine.”

A full year later, Yusuf said that he went to see his local GP, who was shocked at the way he had been treated. The doctor prescribed antidepressants and referred Yusuf to a local mental health support service. Initially, Yusuf had weekly telephone check-ups with a caseworker, during which he discussed his experiences over the previous week, set short and long-term goals and was given advice on coping strategies. He found this support helpful and felt that he was making real progress.

Then, without explanation, the calls were gradually phased out. First, they became fortnightly, then monthly. Eventually, they stopped altogether and Yusuf was referred to a mental health charity with no knowledge of his case or circumstances.

“They rang me on two or three separate occasions, each time starting the whole initiation process again and asking for all my details,” Yusuf said. “Then they never called again.”

In some senses, mental health is a great leveller. Anyone can struggle with it, regardless of their background. The risks, however, are not evenly distributed across society. Socio-economic status profoundly affects our chances of having good outcomes, with working-class communities more likely to experience poor mental health. Cuts to mental health service budgets over the past decade have also disproportionately affected working-class communities, of which many Muslims are part. A 2015 study by the Department for Work and Pensions found that half the British Muslim population lived in poverty compared to a national average of 18%.

Saiqa Naz is the president of the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies. She believes that too many in the mental health profession are quick to blame communities for their lack of engagement with mental health services, when the focus should be on removing the structural barriers that many feel stand in their way.

“People from poorer backgrounds are more likely to struggle and need help. In terms of provision of care, we need to think about equity,” she explained. “More deprived communities require more funding.”

This investment, said Naz, must go beyond mental health services. “Funding infrastructure around communities to help them get back on their feet, into education or employment is so important.”

Covid-19 brought into sharp focus the consequences that inadequate mental health provision can have on society. Services in the UK have been chronically underfunded for years and the number of beds in NHS mental health hospitals has fallen by a quarter since 2010. In December 2020, James Adrian, president of the Royal College of Psychiatry, warned that the increased social isolation and economic insecurity of the lockdown era posed the greatest threat to mental health since the second world war.

Adrian’s dire predictions appear to have been correct. According to the Office for National Statistics, rates of depression doubled during the pandemic. Meanwhile, a recent report by Action for Children states that mental health has become a major concern for young people since the start of the coronavirus outbreak. In 2019, less than a third of children aged 11 to 18 reported concern about their mental health. Now, that figure has grown to 42%.

Vicki Nash is the head of policy, campaigns and public affairs at Mind. She explained that spiralling costs of living are now amplifying the UK’s post-pandemic mental health crisis.

“At Mind we’ve seen a 30% rise in people contacting our helpline about financial difficulties, compared to the previous year,” she said. “As more and more people start experiencing money problems, it follows that more people will need support with their mental health, which will only add pressure to already stretched-to-their-limits services.”

While the lengthy waiting lists, staff shortages and dwindling budgets of the UK’s mental healthcare system are of concern to us all, religious and ethnic minorities face additional hurdles when seeking mental health support. Diversity within the mental healthcare sector is a serious issue that prevents hospitals from providing culturally competent care for large numbers of people in need.

Ethnic minorities make up 13% of the UK’s population but, according to the most recently published NHS Workforce Statistics, only 9.6% of qualified clinical psychologists in England and Wales are non-white. As a result, many British Muslims struggle to find therapists from similar backgrounds to themselves.

Naz highlighted that when British Muslims do access help from therapists, their recovery rates tend to be lower than average. “The Bangladeshi community, for instance, has the poorest outcomes when it comes to recovery,” she said.

According to a 2016 annual report by the Health and Social Care Information Centre, when accessing mental health services Muslims experienced a much lower recovery rate (40.3%), compared to that of Christians (54.5%) and Jews (49.5%)

Naz attributes these statistics to a lack of training given to practitioners providing mental health care to religious and ethnic minority patients. She believes that it is essential to create safe and welcoming spaces that allow patients to bring their entire identity into the room — something that is often extremely difficult to do when doctors and therapists have little knowledge of their beliefs or the communities they belong to.

Naz believes that a number of measures can be taken to address this situation, including providing therapists with better access to literature translated into languages spoken in the communities they serve and allocating time for on-the-ground outreach work.

“If a therapist doesn’t understand the community, hasn’t had the training, and doesn’t have culturally sensitive supervision, that will directly impact the delivery of care,” she said. Don’t wait for communities to come to you. Go into communities and let them know what’s on offer. Help educate them about mental health, so they can identify the signs earlier on.”

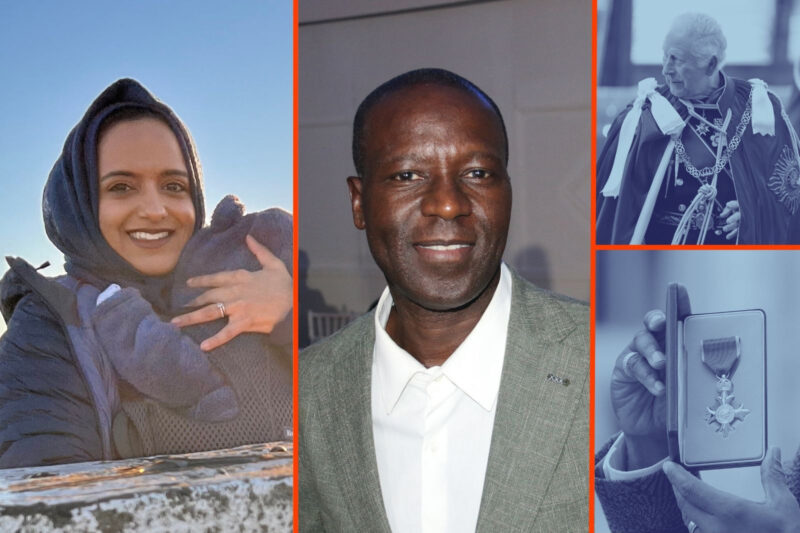

Nafisah, a British Muslim from an Gujarati family in the north-west of England, has sought help from a range of therapists from various cultural backgrounds. Finding the right person has not been easy.

“When I was talking about things related to Indian culture, for instance, the fact that we come from close-knit communities, I found that it was hard for them to understand,” she said.

After working with a few practitioners, she found one from a South Asian background who understood her circumstances and concerns. Nafisah believes that the incorporation of that knowledge into the therapy she was receiving was incredibly valuable.

“They were able to understand how faith and community can be a part of the healing process,” Nafisah said. “It’s not the be all and end all, but it can work in tandem to improve therapy for Muslims.”

Naz adds that providing good mental health care is not solely a matter of resources, but one of acknowledging the problem at an organisational level and taking steps to fix it.

“It doesn’t need to be this way. That’s the frustrating thing. We were commissioned by NHS England to publish a guide back in 2018,” she said. “We’re now in 2022 and I’m still trying to push for it to be implemented in its entirety.”

For now, a significant proportion of mental health outreach work is falling to minority communities themselves. Coffee Afrik is a Somali group operating in the east London boroughs of Hackney, Tower Hamlets and Newham. Funded by a number of organisations including Tower Hamlets Council and the charity Islamic Relief, its central aims include challenging stigma and transforming the prevailing narrative around mental health.

“Ours is faith-based work that honours our communities, our culture and our religion,” said co-founder Abdirahim Hassan.

Coffee Afrik employs three full-time “community connectors” to carry out what it refers to as “detached work”: a grassroots approach in which individuals go into local communities and discuss what mental health problems look and feel like, what support is available and the many ways that psychological distress and trauma can manifest themselves.

“Our engagement is about meeting communities where they are,” said Abdirahim. “We carry out things like barbershop outreach, where we distribute leaflets and actively engage with young Black men in open and honest conversations about mental health.”

He went on to explain that the organisation works with partners, including the East London Foundation Trust and East London Mosque, to bridge the gap between mental health services and local communities.

Muq, a 26-year-old British Somali from east London, is one of many people who have benefited from Coffee Afrik’s work. He is grateful to the group for the way it has helped to normalise the discussion of a topic long considered off limits by many British Muslims.

“Growing up, nobody told me about mental health. I only started to realise when I got older and saw my friends struggling,” he said.

For Muq, Coffee Afrik’s peer-to-peer support groups offer a vital safe space for an honest dialogue around mental health. To facilitate these conversations, the organisation uses what it refers to as the Tree of Life programme, which is based on a South African methodology developed to address the wounds inflicted by apartheid.

“Some of the things I witnessed growing up in inner London, like gangs and youth violence, have been traumatic,” he said. “Tree of Life resonated with me because it’s about identifying what you experienced in your life but not letting that experience define you. The programme talks about how you look beyond that trauma and strive for greatness.”

As well as working with the younger generation, Coffee Afrik also runs group sessions with older British Somalis, which Muq’s aunt has attended.

“The older generation have never really been given an opportunity or a platform to discuss their own mental health and trauma,” said Muq, explaining that his aunt has found the sessions uplifting and empowering.

“People are tired of seeing our communities going through the same cycle and seeing our loved ones struggling with these issues. Now that the conversation is becoming more mainstream, we may have the possibility of actually reshaping how services are provided to the Muslim community.”

In the UK, registered charity Mind provides support, information and advice for a wide range of mental health issues. Calls to Mind’s Infoline 0300 123 3393 from UK landlines are charged at local rates, while charges from mobile phones vary. You can also email info@mind.org.uk. There are also more than 100 Mind local branches across England and Wales.

Newsletter

Newsletter