Dual citizenship will transform the lives of millions of Muslims in Germany

After a longstanding ban, the nation’s government is proposing that people from non-EU countries, such as Turkey, should be allowed to hold multiple nationalities

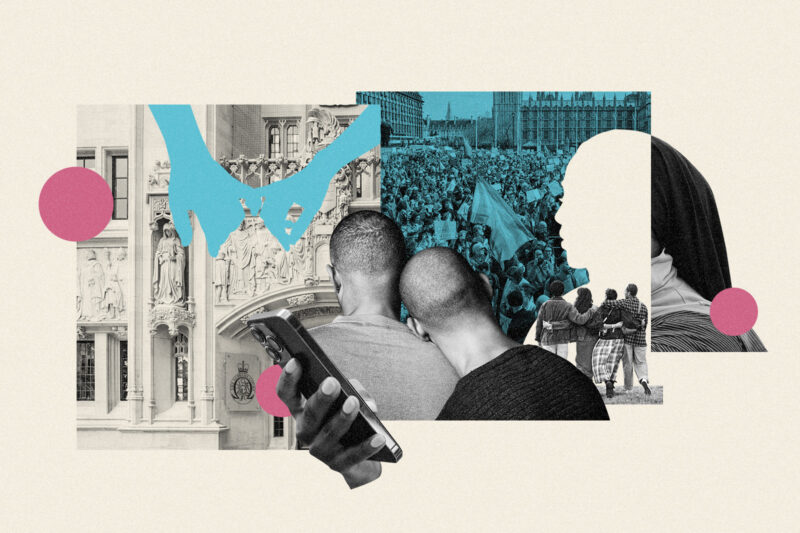

It was a bright spring Saturday at Berlin’s Kottbusser Tor, the heart of the city’s eastern Kreuzberg district. Outside one of the many hole-in-the-wall Turkish food joints that surround the bustling, circular plaza, around 100 people were gathered for a demonstration.

“Voting rights for all!” read a huge sign. Speakers switched between German, Turkish and Arabic, all protesting against the fact that 10 million German residents lack the right to cast a ballot in local or federal elections.

In order to vote in national elections, individuals must be German citizens. Most countries have similar rules, but here obtaining citizenship is extremely difficult. Immigrants from outside the EU are prohibited from holding dual nationality, so many are forced to give up their other passports, should they wish to become naturalised German citizens. Many choose not to take that step. Less than 50% of the country’s largest minority – people of Turkish heritage – have German citizenship, although the community was established in the country more than 60 years ago.

Now, all that could be about to change. Germany’s current government – a three-way coalition consisting of the Greens, the Social Democrats and the liberal Free Democrats – has proposed easing the pathway to citizenship and allowing people to hold multiple nationalities.

“Germany is an immigration country. That is why it is high time we also see ourselves as an immigration and integration society,” said chancellor Olaf Scholz in a December 2021 statement. “This includes facilitating the path to German citizenship. Only in this way can we enable full political participation and, thus, better integration.”

At the demonstration, I met 32-year-old Can Güney Aksakalli, who moved to Germany from Turkey eight years ago. He told me he was weighing up whether to apply for German citizenship, but was worried about losing his right to vote back home. “I would really miss that,” he said, as a musician took to the mic behind us, playing traditional Turkish folk music with German lyrics.

Not having German citizenship can mean missing out on chances of a better life. “A few years ago I was offered a good work opportunity in Switzerland,” Aksakalli explained. The conditions on his visa state that he cannot stay outside Germany for more than six months a year, giving him no choice but to turn the offer down. “The visa process is very stressful and really hard,” he said, adding that he would have to go through it all over again if he returned to Germany afterwards. “All the years that I spent here would have been wasted.”

The proposed shift in policy is partly driven by economics. Germany has a rapidly ageing population and is facing an urgent skills shortage. The current government says it wants to attract 400,000 workers from abroad each year. However, in addition to transforming millions of lives for the better, changes to citizenship laws would mark a huge psychological shift in the way Germany views immigration.

The announcement came not long after the 60th anniversary of the country’s gastarbeitar (guest worker) agreement with Turkey, created to fill labour shortages in post-war Germany. Around 750,000 Turks, largely from rural areas, came to West Germany over the next 10 years, most to work in manufacturing industries.

‘If you have lived here for 40, 50, 60 years and contributed to the economy, then you should be able to be German’

It was assumed that the majority would return to Turkey after a couple of years of saving, but political and economic instability meant that around half decided to stay in Germany, building new lives and communities. Today, areas of Berlin such as Kreuzberg and Neukölln are packed with Turkish restaurants, barbers, wedding shops and even have bilingual schools and kindergartens.

Although they played an essential part in helping Germany become the biggest economy in Europe, Turkish immigrants have faced high levels of discrimination and social exclusion, which persist today. German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier has admitted that the country was too slow to recognise their contribution to society, telling the Turkish daily newspaper Hürriyet last year that “it took a very long time for politics and the people to realise that these so-called guest workers were neither guests nor only workers”.

According to Safter Çınar, a founding member of the Turkish Federation in Berlin-Brandenburg and migration officer for the German Trade Union Confederation, the rules against dual citizenship have intensified that sense of exclusion. “People know that EU citizens can keep dual nationality,” he told me over Zoom. “And this creates a bad feeling in parts of the community, because they feel this is a rule against Turks.”

Çınar, who moved to Germany in the 1960s, is one of the 10% with dual citizenship. He gained it in the 1990s, when Turkey allowed people to reapply for Turkish citizenship if they had given up their Turkish nationality in order to obtain a German passport.

According to Green Party spokesperson for migration Filiz Polat, the centre-right Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU), which held power in Germany for the best part of the past two decades, has been fiercely opposed to previous attempts at reform. The CDU did not respond to a request for comment for this story but, in an interview with state broadcaster Deutsche Welle last year, parliamentary group leader Ralph Brinkhaus suggested that more people would try to enter the country illegally if they knew it would be easier to get German citizenship.

For Polat, gaining citizenship “is an important part of feeling like you are participating in society”. She is also against some of the citizenship requirements, such as German language proficiency and being obliged to prove “acceptance of German norms”.

“If you have lived here for 40, 50, 60 years and contributed to the economy, then you should be able to be German,” she told me over Zoom.

Polat has very personal reasons for backing the proposed legislative changes. Her father, who moved to Germany from Turkey in the 1960s, never applied for German citizenship because he did not believe it was fair that he would have to give up his Turkish nationality. “He didn’t even have the opportunity to vote for his own daughter when I was the youngest ever candidate in state elections in Lower Saxony,” she said.

Unofficially, it is possible for immigrants being naturalised as German to successfully argue to retain their original citizenships — for example if they need them for work-related travel or to care for sick relatives. However, according to Professor Dietrich Thränhardt from the University of Münster, who studies the effect of Germany’s citizenship laws on different migrant groups, “the administration is kinder” to people from countries such as the United States, Canada and Australia than it is to those from the Middle East, Africa or Asia.

‘I always considered myself a global citizen’

Looking at the statistics for naturalisation from 2020, only 10.5% of Turks managed to retain dual citizenship compared with 93.6% of Americans, 90% of Canadians and 75% of Australians. “There is no legal basis” for this, Thränhardt said. “But the approach of the bureaucrats is different.”

This discrepancy angers Demet Sarikaya, 36, who moved to Germany 11 years ago. She decided to apply for citizenship after the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul, during which 22 people were killed while demonstrating against what they saw as increasing government authoritarianism, and the 2016 attempted coup against the government of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

“I always considered myself a global citizen,” she told me during a telephone conversation. “But going through the process, and seeing how easy it was for Americans, for example, to keep their passports, really made me aware of the discrimination.”

The easy, largely visa-free travel that comes with a German passport is viewed as a considerable benefit of citizenship by many people. “I enjoy being Arab – I’m really proud of it,” said Ehab Sukkariya, 24, sipping a coffee outside Berlin Central Station. He arrived in Germany seven years ago and obtaining a German passport would enable him to visit family living in Qatar and Saudi Arabia – something he can’t do on his existing Syrian passport. He also said that doing so would make him feel more secure, given the recent decision of countries such as Denmark that Syrians are now safe to return home.

On Facebook, Syrians applying for German citizenship are sharing their stories and advice. Some groups have tens of thousands of members. For Sukkariya, the strangest part of the process has been visiting the Syrian embassy in Germany and handing over hundreds of euros for documents, including a new Syrian passport, to the government he fled.

“It felt really weird,” he said. “It was like stepping back into Syria. It made me feel sad for my country.”

Syrians are actually able to keep dual citizenship because the government in Damascus won’t let them give up their citizenship. However, this isn’t always clear and a lot of misinformation circulates about the process, leaving many people in the mistaken belief that they can’t apply.

No matter what the motivation for gaining German citizenship, the process of giving up an existing one is always fraught with emotion. “My parents were public school teachers, and they dedicated their lives to educating young people who could contribute to Turkey,” Sarikaya explained. “When I told them about my application, they went completely quiet on the phone. When they finally collected themselves, my mum asked me in a very weak voice why I wanted to be a German.

“I explained, I’m not becoming German, I’m just obtaining a German passport, and it won’t have any implication on my future life and whether I decide to move back to Turkey. But from their eyes, it almost felt like I was this daughter who was becoming a new person.”

Newsletter

Newsletter