Even through bad times there are always people writing a different story

History is full of marginalisation and mob rule, but it is also full of inspiration, progress and hope

I have been known to enjoy a party. Not a party in the Hollywood movie sense, where young people get together and do what my parents would call “fraternising”, but an election party.

I’m the kind of political nerd who loves to get the popcorn out for the exit polls, shouting at the screen, tweeting hot takes at the same time (though I’ve recently switched X for Bluesky).

My election watching has spanned continents: Australia, the UK, the US, France. I remember former Australian Labor leader Kevin Rudd’s overthrow of long-time conservative prime minister John Howard in 2008, and Barack Obama’s victory in the US in 2008. I held my breath as numerous Australian prime ministers stabbed each other in the back and called snap elections, and when I arrived in London in 2017 I found the Brits doing the exact same thing.

I can tell you with clarity where I was when these political moments took place. I find elections fascinating, challenging, infuriating, invigorating. It’s life-altering; it’s the theatre of power.

That’s it, isn’t it? I’m not watching politics, I’m watching a show. I’m consuming the pomp and ceremony, the performance, the game. Recently, I’ve been wondering how my relationship with politics as TV spectacle rather than high stakes power play has affected my ability to make sense of reality and make change.

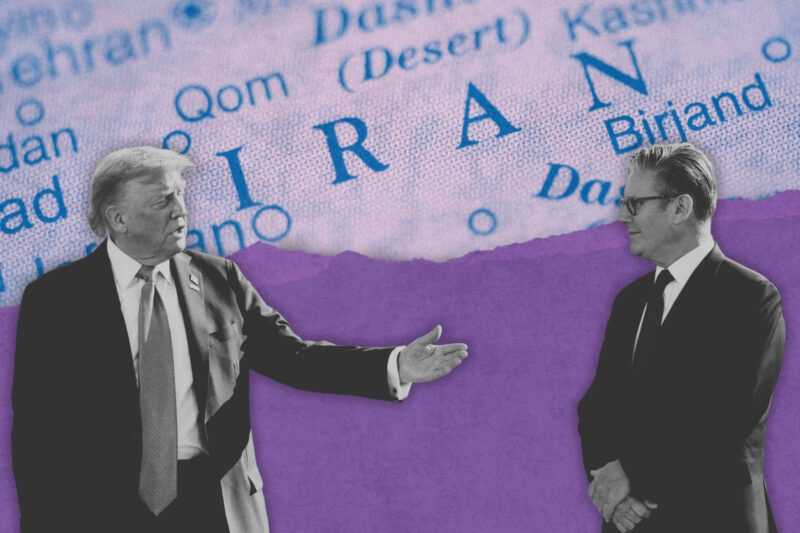

Nothing brought this home to me more than the party I held to watch the US presidential election in November.

We were a motley crew. Brits and Americans from across the diaspora, a few Europeans sprinkled into the mix. We nibbled on snacks and sipped tea, traded memes and tried our best to get CNN to work (it didn’t). There weren’t any strong advocates for either camp in the room, but there was an apprehensive sense that anything could happen. Conspiracy theories were traded and more tea was poured until about 2am, when the results began to trickle in.

It suddenly became very real, especially for our American friends.

As guests excused themselves, I wondered what it must be like to watch your countrypeople make a choice that feels harmful, violent, maybe even morally wrong. What was it like for them to be among us — folks who will be affected in some way by the Trump administration, but not nearly as much as a citizen or resident of the US might? Did it feel like we were treating it as a spectacle?

As I discussed this with British friends, many recalled their memories of the Brexit referendum. They spoke of the days after, the confusion and, in some cases, rage, at the collective decision of a populace. This anger has fossilised, a key plot point in the story of their relationship to this country. They talked about feeling disempowered by the result, by the closing of opportunities and of imagined futures. They talked of a sense of loss and despair. While sharp edges of those emotions have been blunted by time, the pain remains.

I don’t have a comparable personal experience. I had left Australia by the time of the Voice referendum, the brutal rejection of constitutional recognition for First Nations people and a major setback for many progressive movements in the country. Despite not experiencing the same sense of betrayal that these elections or referendums symbolise, I still wonder: how are we meant to process these wild political changes? I have questioned this many times amid increasing polarisation in recent years, and I’ll no doubt question it again in the run up to Australia’s federal election in 2025. Rejection is bad enough at the interpersonal level, how do we manage it on a national scale and not let it push us backwards?

There will be many stories told about what happened in the US this year, competing narratives clamouring for supremacy. But as I gorge on analysis, I am trying to remind myself to not get too caught up in the game. To not get lost in the day-to-day emotional turmoil that accompanies following any sport. I am trying to remind myself that humans have always been this way — this is not new, this is how it goes.

History is full of marginalisation, mob rule, monarchs and megalomaniacs. History is also full of inspiration, negotiation, progress and hope.

The thing about watching a game is that you’re outside it. You’re a spectator. The moment a person considers themselves a viewer rather than a participant, they cede their power. But politics is not outside us. It is in us, we make politics happen — even choosing not to actively exercise power is a political choice.

Things are bad. They are bad in so many parts of the world: Sudan, Palestine, the US and more. But history is full of bad times, and in all these places and through all of these moments, there are people writing a different story. I don’t want to sell false hope — there’s no value for us in that. But the story is never finished. We might as well try our hardest to make the most of the life we have, because one day we will be asked: what did you do with the time I gave you?

I want to have a good answer.

Khair, inshallah.

Newsletter

Newsletter