Board game nights are bringing Muslim communities together

In a city where belonging can be hard to find, cafes are helping people to connect around something timeless

It’s nearly 7pm on a Friday in late October and, while most Londoners are rushing to catch the tube home, the Kismet Café is coming alive. On a street corner in the east London district of Whitechapel, every fortnight this warm, wood-panelled event space dedicates itself to all things board games.

Since Kismet’s opening in June, the games nights have proved a runaway success. When I visit, tables are filled with regulars, first-timers, friends and strangers, all engrossed in games including Codenames, Articulate and Monopoly.

“Eighty people signed up for our first night,” says cafe manager Nudžejma Softić. “Some people were sitting on the floor because we didn’t have enough space at the tables.”

Most households have a dusty box of Scrabble tucked away somewhere, but the enthusiasm for Kismet’s game nights is part of a wider emergence of board games as a social activity that people are willing to go out for. Some observers trace this relatively new-found popularity to early 2021, when the UK government’s Covid-19 restrictions began to ease and people were looking for ways to connect with others after a lengthy period of isolation.

If you’ve noticed board game cafes and game nights cropping up in your area, that’s because it’s a genuine national trend. In the past few years, dedicated spaces have popped up from Glasgow to Plymouth. According to a 2025 report by the market research organisation Technavio, the global board games market is projected to reach a value of $5.17bn (£3.9bn) by 2029.

But there’s another layer to this phenomenon. For many Muslims, board games have powerful cultural significance, from traditional South Asian games such as carrom to backgammon in Iran and the Middle East. Game nights also offer a halal option for anyone seeking a good night out and opportunities to meet likeminded people.

For Softić, who is from Sarajevo, games have long provided entertainment and an easy way to connect with others. Having moved to the UK in 2020, she wanted to continue that tradition. “In Bosnia, I was really engaged in different communities and clubs,” she says. “Every week, I would make lunch, invite people over and we would play games. When I came here, I was really missing people and being surrounded with all my friends. I had to create a new community.”

Now, just five months after Kismet’s opening, Softić says the game nights are the cafe’s most popular event. “There are a lot of regulars,” she says. “I see the same names on the lists.”

Hassan Butt, 40, is one of them. “Games take the pressure off and help people open up,” he says. “It’s nice to break out of your routine and come to events like this. People are really open and friendly. When I came alone last time, you could just jump on a table with people and ask to join.”

For Anoushka Qazi, 25, who moved to London from Dublin a year ago, both Kismet and its game nights have offered a feeling of belonging.

“Board games are really easy,” she continues. “Everyone’s on the same vibe, it’s very relaxed. You build a community within a community. There aren’t many Muslim-owned spaces in Ireland that make you instantly feel seen and understood, but here it feels like home. It’s the small things that make it comfortable, like the Islamic gallery at the back or the Palestine flag hanging in the corner.”

Qazi is accompanied by her friend Kamariyah Ahmed, 27, who explains that ludo is a well loved game among British Pakistanis. “Our family is crazy about it,” says Ahmed, laughing. “We even custom order our boards from Pakistan.”

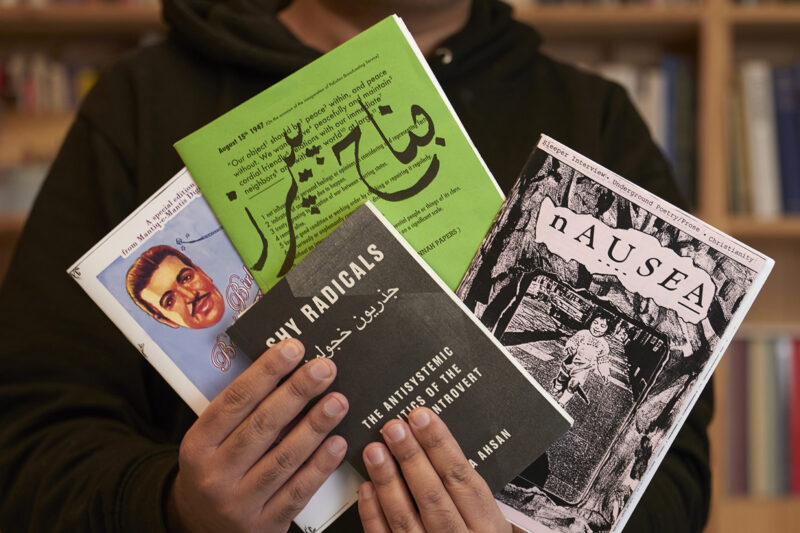

Beyond the growing number of social events for players, a new wave of creators are designing games rooted in cultural identity, from Glowborne, a South Asian reimagining of chess, to Samosa, a desi take on the description-based game Articulate. Aisha Aldris and Nour Abosaif have created their own conversational card game, Culture Mocktail, to help people from mixed cultural backgrounds connect with one another.

“Navigating life between cultures isn’t always the easiest journey,” says Aldris, who describes herself as half-Syrian, half-Irish. “We wanted to create a game that would discuss what it means to grow up between different cultures and how to embrace your cultural identity.”

Culture Mocktail consists of 130 prompts split into five categories: open, connected, fearless, focused and reflective. “The whole point of the game is to get people to ask the deep questions,” Aldris says.

Having taken the game to different community spaces around London, Aldris has seen first-hand how playing can bring people together. “We’ve built friendships through Culture Mocktail and met some amazing people,” she says. “It’s a huge way to connect with people and push away the small talk.”

Back at the Kismet Café, three friends who’ve known each other since primary school are sitting together, getting ready to play Monopoly. They tell me that they were invited to the night by a friend, who they had met at another event dedicated to carrom.

“It’s nice to come here and have fun and be present,” says Nusaiba Chowdhury. “Especially with social media and everyone normally being on their phones.”

“It’s also a cheap way to have a fun night,” adds her friend Sumayya Yasmin. As we speak, a girl who has arrived at the cafe alone shyly asks to join the table. By the end of the night, everyone is laughing together.

Hassan Khan hosts Kismet’s game nights and has enjoyed helping to create an environment where such friendships can be made. “I see people come again and again,” he says. “I recognise them, ask what games they like and we buy them. It’s all very community-driven.”

Across the room, people who met at previous nights greet each other like old friends and conversation, laughter and the occasional victorious shout fills the room. It’s exactly the vibe Softić wants at Kismet’s game nights and her own way of bringing all of London together.

“You get to know each other better,” she says. “At our cafe, the owner is Pakistani, I’m Bosnian, our barista is Algerian and another is Bangladeshi. We are all from different communities and that’s what we want to bring here.”

Newsletter

Newsletter