‘The diversity is so beautiful’: 25 years of the London Palestine Film Festival

Over the years, the LPFF has tracked the shifting political landscape in Palestine and Britain, revealing how the meanings of films change and reflect the world around them

The London Palestine Film Festival (LPFF) began long before Palestinian cinema entered the vocabulary of mainstream British cultural institutions.

Its origins lie in a small event put on by a student society at Soas University of London 25 years ago. When founder Khaled Ziada, a Palestinian who had come to the UK to study, talks about those first years, he reminds you how fragile the foundations were; how significant it was for Palestinian stories to be seen, particularly since there have been no cinemas in Gaza since Israel destroyed them during the first intifada in the 1980s.

“Things were difficult to document in those days,” says Ziada. But the ethos was clear and inclusive. “Our festival is about Palestine. It’s not necessarily Palestinian films only, or made by Palestinians. We will invite any film-maker making films on Palestine to be part of this.”

The earliest programmes consisted of documentaries on the second intifada, films on refugee life, and work tracing the violence and ruptures shaping everyday existence. As the LPFF expanded, so did its scope.

The festival moved to the Barbican in 2004, at the height of the so-called war on terror when the British media landscape was saturated with Islamophobic rhetoric and narratives that cast Palestinians primarily as security problems. But by that point, LPFF was well-established enough to provide a counter-narrative. It was situated in a respected London institution even as the political climate was hostile to nuance.

“The Barbican became our home,” Ziada says, describing how the move altered the visibility of the event, which now straddles London’s finest cinemas including The ICA, Curzon Soho and Garden Cinema, while still screening at Soas.

While news audiences were being given a heavily filtered image of Palestinian life, the films shown at the festival offered something else. Ziada sees the LPFF’s rising prominence as vital — something that goes beyond rallies and protests.

“When people show interest to watch films in relation to Palestine, that shows there is increased interest from the public to learn more,” he says.

The relationship between political reality and cinema is clearest when looking at the festival’s past. In 2001, Brian Whitaker, the Guardian’s former Middle East editor, wrote that the media’s biased reporting meant Israel was winning the “war of words”. The LPFF continually countered that narrative, showing films that proved that Palestinians are a people deserving of dignity and human rights. As well as preserving Palestinian culture, the festival gave film-makers, activists and poets a stage to discuss their work and the truth of life under occupation.

In 2003, Juliano Mer-Khamis and Danniel Danniel’s documentary Arna’s Children — shot inside the Jenin refugee camp — echoed the trauma of the 2002 massacre, when Israeli forces attacked the camp. The film traced how young people who grew up under siege later took up violent resistance or were themselves killed.

When Hollywood was making despicably anti-Palestinian films — such as Bruno and You Don’t Mess With the Zohan, which made light of people living under an apartheid state — the LPFF was one of the few places in the UK where audiences could see Palestinians through a fully human lens. In 2009, the opening-night featured a screening of Rashid Masharawi’s Laila’s Birthday, a portrait of life under occupation told through a single day in Ramallah.

The film’s selection came in the immediate aftermath of Operation Cast Lead, a major Israeli military offensive in Gaza and, with its deceptively simple structure, reflected the claustrophobia and despair of the time.

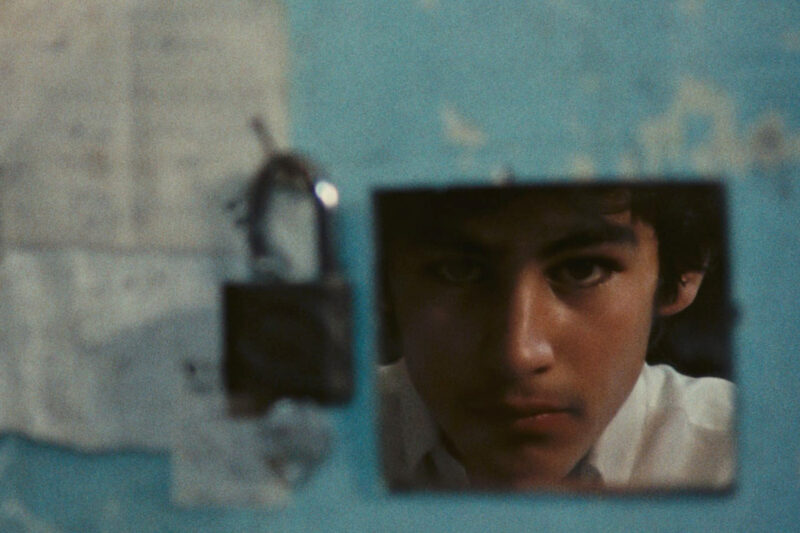

A decade later, in 2018, LPFF opened with Raed Andoni’s Ghost Hunting, a film created with former prisoners who reconstructed the torture and trauma endured at an Israeli detention centre. It was released shortly after the start of the Great March of Return protests on the Gaza-Israel border, which between March 2018 and December 2019 demanded the right of return for refugees and an end to the Israeli blockade. The demonstrations were met with violence from Israeli forces, in which 223 Palestinians were killed. The period was also marked by renewed focus on incarceration and collective punishment.

Only in recent years has Palestinian cinema begun to receive global recognition, largely thanks to events such as LPFF, social media and online platforms. In 2024, Mahdi Fleifel’s To a Land Unknown became one of the festival’s major titles, arriving during the ongoing genocide in Gaza and dealing with themes of forced displacement and the seeming impossibility of return.

Ziada is direct about how recent events in Palestine have shaped the scale and purpose of the festival. “For unfortunate reasons, our audience number almost doubled since the genocide started,” he says. He does not romanticise this surge and instead interprets it as a sign that people want perspective beyond headlines. “The beautiful thing is people are not only looking at Palestine when there are massacres happening. They want to learn more about the history and culture. They want firsthand understanding, learning directly from film-makers about society, politics, everything.”

The growth of the audience has changed the demographic too. An event that was once attended mainly by older diaspora communities now draws a wide cross-section of viewers.

“Our audience is very diverse. Arabs, Palestinians, non Arabs, people from the Jewish community, English, Europeans. The diversity is so beautiful,” says Ziada.

The featured films reflect that evolution. In recent years, works such as No Other Land, To a Land Unknown, From Ground Zero, and The Voice of Hind Rajab have travelled internationally, bearing witness to unfolding atrocities and producing a robust archive of contemporary Palestinian life. Others, including Once Upon a Time in Gaza and Palestine 36, interrogate the historical structures that form the present.

A festival dedicated entirely to Palestine occupies a charged space in Britain — even if that is often unspoken. Yet the LPFF has successfully avoided institutional interference. “We have enough credibility,” he says, and the cinemas involved in the festival have “never interfered in our programming”. That stability contrasts with the early years, when screening films about occupation and Palestinian political life was treated as controversial in itself.

Ziada is clear that the festival’s ongoing success is not a simple story of resilience in a competitive film industry. “It is still very, very difficult for Palestinian film-makers to find the right budget and to do the film they really want to make,” he says.

Digital technology has widened access in theory, yet economic conditions, movement restrictions and destruction of infrastructure in Palestine mean the field remains profoundly unequal. Some films are made with extremely limited resources while others rely on European co-production money, which still comes with challenges. Even in the best case scenario — with No Other Land winning an Oscar, for example — distribution and a solid chance of a return on investment isn’t guaranteed.

When asked about the future of the LPFF, Ziada rejects the idea of expansion as the main goal. Instead, his focus is collective growth. New Palestine-focused festivals are emerging in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Leeds, and beyond. Rather than thinking of the London festival as a central authority, he sees it as part of a distributed network committed to cultural preservation and political clarity.

The LPFF began as a modest, safe space for Palestinian stories, but it has become a critical public arena where the politics of representation, memory, occupation and cultural survival converge. Through the years, it has tracked the shifting political landscape in Palestine and in Britain, revealing how the meanings of films change as the world around them does.

Ziada reflects on this with a quiet certainty. “What we are going through as Palestinians will continue to have its part in film-making,” he says. The commitment to bearing witness is only growing. That is not simply an artistic prediction; it is a proven truth that the festival has made visible for 25 years.

The London Palestine Film Festival is on at various venues across the city until 28 November.

Newsletter

Newsletter