Sudan Retold: a rich blend of art and unheard stories

An immersive exhibition and accompanying book shed new light on the nation’s past, present and future

In paint, photography and prose, the long and complex history of Sudan is on display at Almas Art Foundation in south London. Sudan Retold, an exhibition and accompanying book, brings together stories ranging from the Nubian matriarchs who fought the Roman empire more than 2,000 years ago to neighbourhood women’s associations in modern-day Khartoum.

Curator Larissa-Diana Fuhrmann, who has worked on the project for almost a decade, first travelled to Sudan in 2009. While completing a degree in African and Islamic studies at the University of Cologne, she took classes in Arabic at the University of Khartoum. There, she discovered a country whose diversity and rich cultural heritage are rarely acknowledged.

“I think we’re very miseducated about Sudan,” she says. “I wanted to educate myself in terms of a culture and a history that is very neglected in narratives around the world.”

Artist and cartoonist Khalid Albaih conceived the project after growing up in Qatar, where he often found himself having to explain where he was from and painting a “mental image” of Sudan for others. He later approached Fuhrmann with the idea.

“He wanted to work with other visual artists inside the country to see what narratives could be told to replace some of the prejudices people have when they hear ‘Sudan’,” says Fuhrmann.

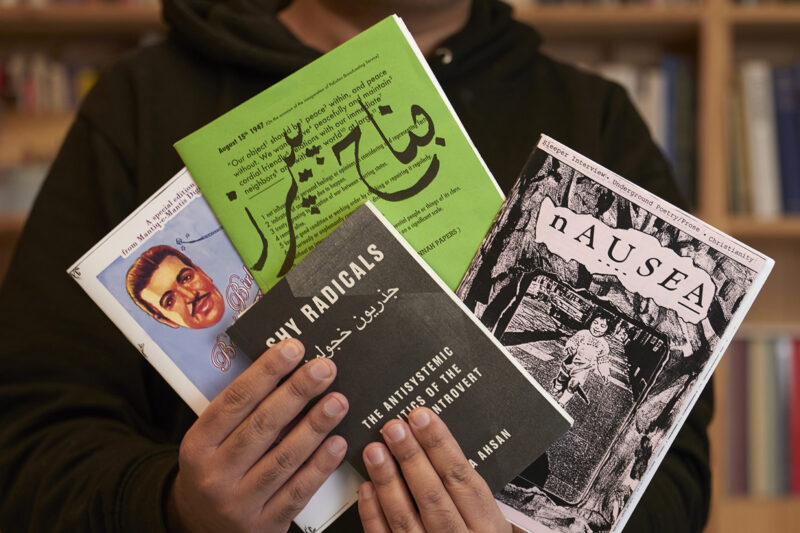

That idea became the print version of Sudan Retold, an anthology exploring the past, present and future of the nation. The first edition was published in 2019 after years of collaborative workshops that brought together Sudanese artists, illustrators, writers and historians from across the country and its diaspora. But as the project was taking shape, the Covid-19 pandemic hit.

“We could never really travel and celebrate this book the way it was meant to,” says Fuhrmann. “The artists didn’t get the recognition they should have.”

Now, Sudan Retold: Edition 1.5 revisits the original version of the book with new chapters and reimagined works.

“We had the chance to continue working on it. There were so many new stories,” says Fuhrmann. “We just kept on creating. We titled it Edition 1.5 because it’s partly the first book and a bit new, but there’s so much more to come.”

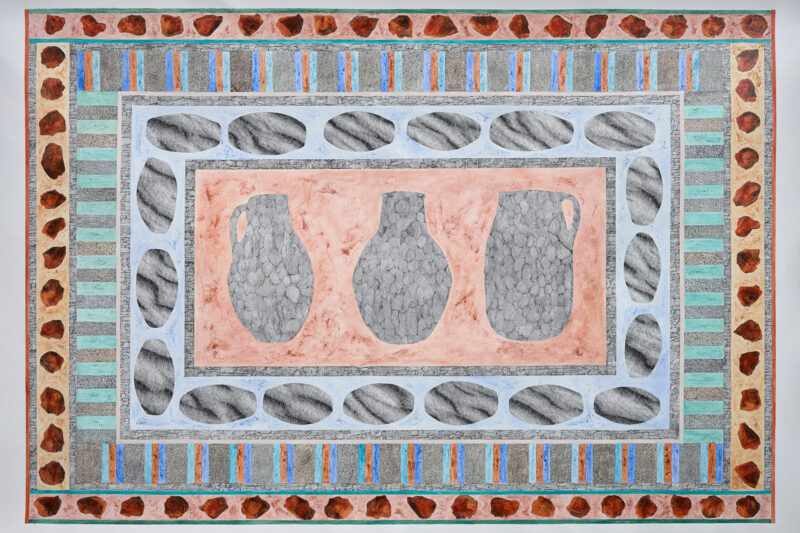

Among the featured artists is Reem Aljeally, a Cairo-based visual artist and curator. Her photographs and mixed-media pieces depict the longstanding tradition of neighbourhood women’s associations in Sudan.

“I took the photographs while accompanying my mother to one of the meetings,” she says. “These ladies are all our neighbours — they support each other during important events, so they have to live near each other.”

Her map-like artwork highlights the homes where members meet each week, while another piece visualises the sanduq — a rotating savings fund that supports members during weddings, funerals and other times of need.

“It shows how they are adaptive to the needs of the community and the changes that happen in the country economically,” she says. “Interestingly, these things happen in the house, very hidden. If you don’t know this dynamic, you wouldn’t see it anywhere.”

Through these details, Aljeally captures a side of Sudanese life largely unknown beyond its borders.

“There are so many preconceptions about what Sudan is and what its people are like,” she says. “I hope visitors walk away feeling the richness, because there’s so much to see beyond what you see in the media.”

The exhibition’s backdrop is a country in crisis, where war has displaced more than 12 million people and threatened the survival of art institutions. For Fuhrmann, art itself is part of the resistance.

“Since the revolution, art has been at the forefront of a lot of the discourse,” she says. “It’s incredibly important as a catalyst — resisting erasure, resisting oppression and violence, and creating visibility for Sudan and its stories.”

She also believes the international art world could do more. “It’s incredibly difficult for a lot of Sudanese artists,” she says. “Those who have fled face structural issues — finding galleries, finding spaces to work in. What could be so beneficial is if arts institutions opened up channels specifically for these cases, just like it happened with Afghanistan and Ukraine.”

“These artists are incredible storytellers,” she adds. “They should be recognised as the artists that they are, not just because of their circumstances.”

For Aljeally, archiving and preservation are vital to her work. “We’ve lost a lot of art spaces in Sudan, a lot of artworks, a lot of artefacts,” she says. “I’ve been working with my team on the Sudan Art Archive, which aims to document and archive Sudan’s art over the past half-century. Through these works, we’re trying to keep our stories, our narratives, our cultures alive.”

While Sudan Retold continues to attract visitors, it is just the beginning for Fuhrmann.

“It’s an ongoing project,” says Fuhrmann. “We’ll continue working on it for hopefully another decade, because there are many more stories.”

The Sudan Retold exhibition is at Almas Art Foundation until 14 December.

Newsletter

Newsletter