The Celebrity Traitors shows unspoken bias at work

Despite its politeness and popularity, the UK’s favourite reality TV show is based on kneejerk assumptions about who people really are

This inaugural season of The Celebrity Traitors promised a glitzy new era for the UK’s favourite reality TV show: a castle full of glamorous celebrities, designer outfits around the breakfast table, a vague motive of charity rather than personal gain as far as prize money is concerned. Yet, even under all that perfectly tailored tartan, the show can’t hide what it reveals: who Britain instinctively trusts, and who it doesn’t.

The show, which comes to its much-anticipated finale on Thursday, has lined up a socially progressive bunch of contestants: writers, comedians, campaigners and influencers. Within days, though, the first to fall were the Black contestants. No slurs, no overt hostility, just a steady, polite consensus that they “felt off” somehow.

That’s how unconscious bias works. In a social deduction series akin to popular games Mafia and Werewolf, contestants can be eliminated in two ways, you can be “murdered” by the three selected “traitors” — in this case Jonathan Ross, Alan Carr and Cat Burns — or be suspected as a traitor by the collective and voted out at the round table. If any traitors remain at the end of the game, they take the prize pot. If all remaining players are “faithful”, they split the money equally between them.

The first contestant voted out, YouTuber Niko Omilana, was labelled a potential traitor immediately. When it came down to the round table, despite presenting an extremely sound argument for why it couldn’t be him, groupthink prevailed and a faithful was banished. Next to be voted off was former EastEnders star Tameka Empson, the rest of the group convinced of her treachery by actor Mark Bonnar, based on his feeling that her demeanour was suspicious.

The one remaining Black faithful, Professor David Olusoga, has stayed in the game by the skin of his teeth, narrowly escaping banishment when voting led to a draw. Since then he has been met with much suspicion, largely because the other contestants are perplexed that he’s still around.

There are precedents for the way the UK version of the show has played out. In season two of the US version of The Traitors, the first contestant out was Peppermint — a black trans woman. Host Alan Cumming described it as “a bad look” and Peppermint reflected upon the decision at the cast reunion, saying “people have to rely on the biases that they bring into the game, which end up targeting whoever is the most different from the group”. Similarly in the last regular series of the UK Traitors, Muslim contestant Dr Kasim Ahmed was banished for smiling and Fozia Fazil returned after being eliminated first, but only lasted two more episodes.

Diversity and inclusion specialist Yassine Senghor told me she wasn’t shocked that Black contestants hadn’t fared well in the show. “When you don’t really know people yet, you lean on what you already believe about them,” she says. “So, even when contestants are giving their reasons — ‘Oh, they’re a content creator,’ and ‘They seem a bit edgy and polarising’ — that’s still sitting on top of preconceived ideas. Would they find the same thing suspicious if it was a pretty white content creator? I’m not convinced.”

Senghor’s point cuts to something uncomfortable about The Traitors. The players convince themselves they’re reasoning when they’re actually presuming.

“What’s really interesting is not just who they pick, but how they explain it,” adds Senghor. “That’s where you see people’s delicacy, what they think they’re allowed to say about different people. They’ll call someone ‘strong-minded’ or ‘divisive’ or ‘quiet’, but those words mean different things and have positive or negative connotations, depending on who you are.”

The Traitors castle doesn’t create bias — it concentrates it. People reach for stereotypes because they have nothing else to go on and television rewards certainty over doubt. Once a person has been labelled “untrustworthy”, the label spreads like wildfire through the group and there’s no real way back.

Senghor sees the high-pressure environment of the castle as the perfect laboratory for bias training. “It’s actually a really cerebral show,” she explains. “You’re questioning what you think about other people and you’re questioning yourself at the same time. That’s what bias work does, it forces you to ask, ‘Why do I think that? What evidence do I actually have?’ It could make the game richer if they leaned into that.

“But it can’t just be contestants doing the work. Production has power too. If you’re making a show that’s literally about judging people on vibes, then you have a responsibility. Either you’re feeding public bias or shaping it. Neither is neutral.”

Those words are a sharp reminder that television directs and reinforces our instincts as much as it reflects them. Reality TV has always done this. Big Brother showed us that racism doesn’t fade under studio lights, with white contestants more likely to nominate contestants of colour for eviction than their white counterparts. Love Island proved that racial hierarchies are alive and well in the world of desirability, with black women consistently the last to be picked in the first set of couplings. The theme of the The Traitors is one of suspicion rather than seduction, but the story remains the same.

Behind-the-camera responsibility matters, especially as the BBC and other broadcasters strive to appear balanced and not alienate any large segment of their audiences. Viewers watching with phone in hand ready to post on social media are quick to call out obvious prejudice, but less good at noticing when bias hides behind good manners or works in the favour of others in certain ways, with obvious traitors flying under the radar as they are ignored or underestimated.

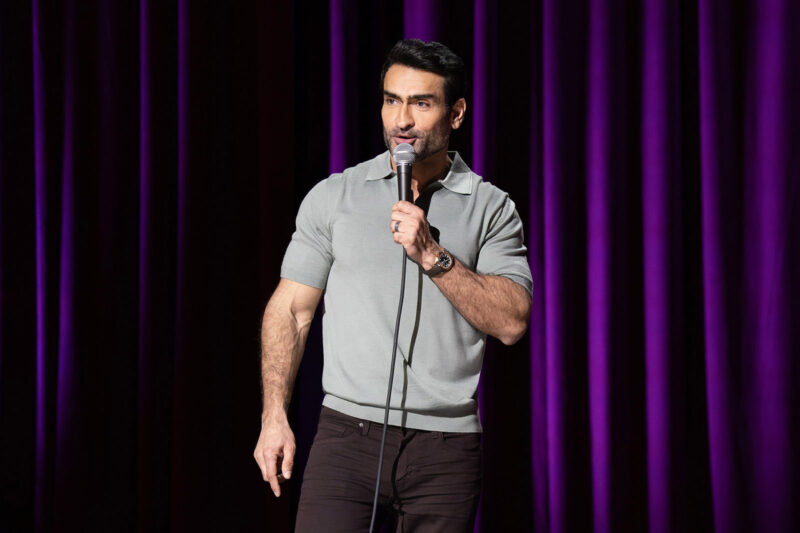

Senghor says that tension is perfectly illustrated by one contestant. The singer and traitor Burns has avoided suspicion almost entirely. When Stephen Fry appeared to have some doubts about her seeming much more exhausted than everyone else, she simply referred to her ADHD and autism as the cause and was questioned no further.

“It’s that classic liberal thing,” Senghor said. “People don’t want to be seen picking on someone who’s neurodivergent or queer or a person of colour, so they put them in a protected box. But that still isn’t seeing the person — it’s bias wearing nicer clothes.”

The Traitors may be a game about deception but its players are, in many ways, performing honestly. They spend hours attempting to prove that they’re decent, reasonable, open-minded people — exactly the image that celebrities need to project in 2025. Yet, even inside that performance, their gut feelings and snap judgments tell the real truth.

If anything, the show’s politeness makes its biases more revealing. No one hurls insults or raises voices. They simply look at someone and decide, “not one of us”. Then they explain it in a way that sounds perfectly rational. It’s the same process that plays out every day in workplaces, social circles, casting meetings and comment threads.

The temptation is to see The Celebrity Traitors as harmless fun. And, on one level, it is: Celia Imrie farting, Carr hamming it up and host Claudia Winkleman going full panto villain, dressed in gothic glamour and treating every murder like someone has genuinely died. But look closer and it’s an experiment in perception, showing how quickly even the most elite liberal crowd resorts to old assumptions.

Newsletter

Newsletter