‘Weaving as a way to think about the world’: the new generation of textile artists inspired by tradition

Raisa Kabir’s new exhibition — titled Tiger, Tiger. Silk Throat… — comes at a pivotal moment for textile art, as weavers bring historical techniques to gallery spaces

When the artist Raisa Kabir was growing up in Manchester, she was often struck by the names given to former packing and shipping warehouses in the city centre: Asia House, Velvet House, India House.

School trips took her to old cotton mills, remnants of the city’s heyday as a linchpin in the textile industry, where tours focused on the history of child labour in the factories, but eluded mention of how the mills were entrenched in systems of colonial extraction.

“No one ever mentioned that the cotton was from India, or handpicked by enslaved people in the American South, the Caribbean or Brazil,” she recalls.

In Tiger, Tiger. Silk Throat… an exhibition of Kabir’s new work at central London gallery Indigo+Madder, the titular piece is a textile of red silk, cotton warp, gold and metallic yarn that hangs from a cast iron frame. The motif recreates a 19th-century Kalighat painting depicting the Dhaka-born wrestler Shyamakanta Bandyopadhyay entangled with a tiger. The pair’s embrace is at once tense and tender.

“It’s not just a fight. It’s also a feeding, a caring. A beautiful, sort of erotic tussle,” Kabir explains. “For me, it was really an antidote to the Edward Armitage painting,” she says, referring to Retribution, painted by Armitage a year after the Indian rebellion of 1857 against British East India Company rule. In the piece, a personified Britannia muzzles a tiger, emblematic of the anticolonial resistance.

Kabir’s textile practice excavates histories of rupture through silk, cotton, jute and indigo. She has exhibited work at the Whitechapel Gallery, Liverpool Biennial, Glasgow CCA, and New York’s Ford Foundation.

Tiger, Tiger. Silk Throat… comes at a prominent moment for textile art, as a new generation of weavers employ traditional techniques and fibres within a contemporary visual context.

Coinciding with Kabir’s exhibition is Malaysian-born Marcus Kueh’s Smooth Sailing, at Manchester’s esea contemporary, drawing on Borneo’s ancestral weaving traditions to explore histories of labour. Sagarika Sundaram, at Alison Jacques gallery, uses the ancient textile of felt to create membrane-like folds, while at Frieze London, British-Thai artist Mark Corfield-Moore turned to the Thai weaving method ikat.

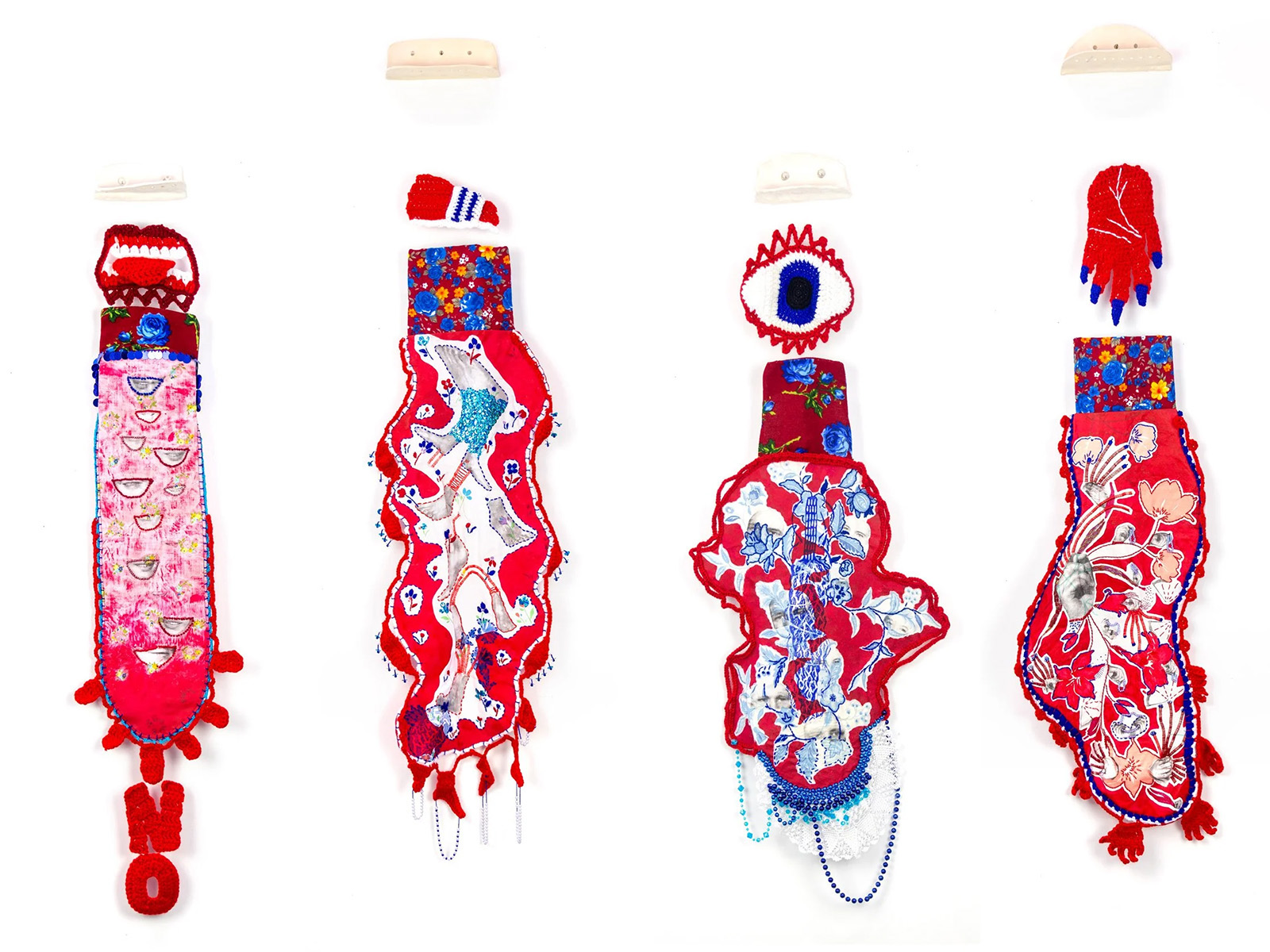

In her own practice, Chicago-based Turkish artist Hale Ekinci creates large-scale fibre sculptures of acrylic yarn crochet, as well as embroidery paintings in which family photographs from personal and found migrant archives are transferred onto textiles using solvents. Turkish traditions, such as oya — decorative lace edging — are frequently incorporated.

“I am interested in how women use coded language to express sentiments that they couldn’t often express openly, through oya or kilim symbols,” she says. Ekinci is drawn to the symbolic meaning behind Ottoman patterns and how figures of authority used them to assert power. “A lot of these symbols are quite feminine, like the carnation or the tulip, and their use by men is intriguing to me.”

Western fine art traditions, Ekinci says, have historically excluded crafts and women’s work from the art market. “This undervaluation has roots in the patriarchy and must be changed, hence my use of these techniques in the white-wall gallery.”

In recent years, major European institutional exhibitions have sought to remedy that exclusion by foregrounding women artists working with fabric: Cecilia Vicuña, Olga de Amarel, Mrinalini Mukherjee — a previous generation of practitioners, whose presence in museum collections signifies a curatorial shift.

“Textiles are no longer suspended within the traditionally hierarchical divide between craft and art — a distinction that is increasingly dissolving,” Krittika Sharma, the director of Indigo+Madder tells me. “They have emerged as a powerful medium through which to express global narratives.”

The boundaries of what demarcates contemporary fine art practice by women, Kabir adds, has been expanded to include women from the global south. “In the 1960s, textile art was situated within an American and Eurocentric point of view and dominant narrative of what it was and who it was done by.”

Women artists of colour were largely “disbanded from that narrative”, while the embroidery inherent to South Asian textiles and other indigenous weaving practices were viewed as decorative or traditional, she says.

It was during a 2018 lecture on Indian textile history that Kabir first heard of lampas, a complex technique that involves weaving with two warps and two wefts, on fine fabrics such as silk. Though lampas is frequently ascribed to Europe, Kabir, who uses the method in her new body of work, found that it could be traced back to the 10th century in the areas constituting modern-day Iraq and Iran, and subsequently in China, India, Turkey and Egypt. Following the Mongol conquest, weavers under the Abbasid Empire took their craft towards other metropoles.

“Contemporary jacquard textile design and the first looms were built on the foundations of the knowledge of these Muslim weavers,” Kabir says. “The history of these provenances is often obscured in the cultural imagination.”

In her use of the technique, Kabir seeks to illuminate its origins, as well as the cyclical histories of revolt, imperial conquest, and appropriation through which it endured across disparate geographies and times.

“I’m interested in how designs, technologies, and authorship change, move, and mutate,” she explains.

Among Kabir’s latest works is a piece replicating the structure of a 14th-century lampas textile from the Nasrid period in Spain. On the fabric, she wove text from a poem written in Bangla with her mother.

At its heart is the notion that the weaver is “the one who can reweave a new future, a new way of thinking, just because of the way their mind works, the long lineages of that,” Kabir says.

“I wanted to think about structures and systems and weaving as this way to think about the world. How do we dream about a world that isn’t the one that we have right now, and what does that look like?”

Raisa Kabir’s Tiger, Tiger. Silk Throat… is showing at Indigo+Madder until 8 November.

Newsletter

Newsletter