A spooky guide to Muslim horror movies

It’s the perfect time to revel in a little haunting — and this watchlist shows that Hollywood does not hold the monopoly on Halloween scares

Across the Muslim world, film-makers have been crafting horrors with their own cultural twists: jinn instead of killer clowns, possession tales rooted in lived spiritual traditions rather than evil dolls, and the sort of bombastic satire that horror does best.

The world is a terrifying place and I find there’s catharsis to be had in watching other people live out nightmares from the relative safety of my own living room. Halloween is the perfect time to enjoy a little haunting — and Hollywood certainly does not have a monopoly on movie scares. There’s further joy to be had inseeing the breadth of global talent’s contribution to my favourite genre. This watchlist takes you from vampire capes in 1960s Pakistan to modern nightmares in Tehran and Indonesian zombies.

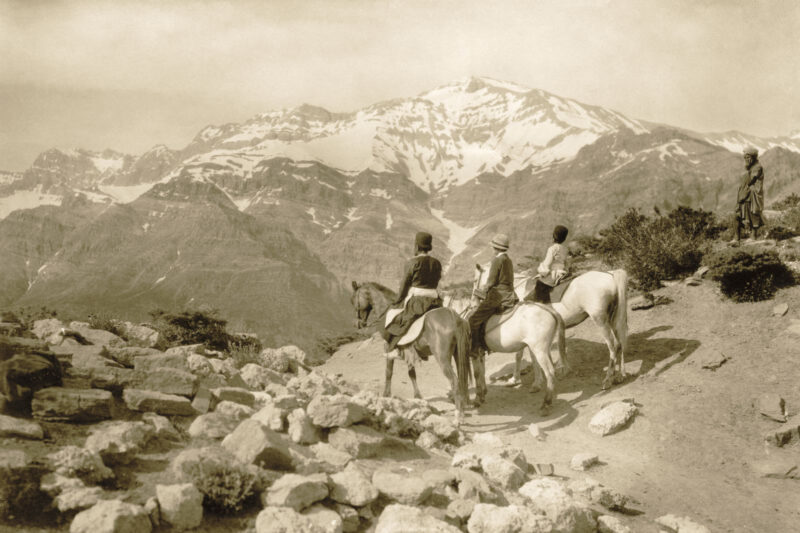

Zinda Laash / The Living Corpse (1967 — Pakistan)

Directed by Khwaja Sarfraz, this eerie Urdu-language riff on Dracula is widely considered Pakistan’s first horror film. It follows a doctor whose experiment in immortality unleashes vampiric consequences, although the word “vampire” is never used. Zinda Laash is all shot in crisp black and white and the blend of gothic atmosphere and 1960s Pakistani melodrama have made it a longstanding cult classic — despite its brief ban in Pakistan for being too provocative.

It has since resurfaced as a midnight screening favourite. Seen today, the film is a fascinating time capsule: a Muslim-world film-maker reclaiming classic horror tropes and filtering them through local style and customs with wild abandon.

Şeytan (1974 — Turkey)

A remake of William Friedkin’s classic The Exorcist, Metin Erksan’s Şeytan is more than a pastiche. It’s an example of how fear transforms across cultural boundaries. Catholic ritual becomes Turkish spirituality and geopolitical anxiety, Georgetown becomes Istanbul, and the original script’s religious anxieties take on new context in a Muslim-majority society grappling with modernity and living on the cusp of western civilisation while still being othered by it.

When Şeytan was released, critics didn’t quite know what to make of Erksan’s work or comprehend its profundity, but decades later, restorations and festival retrospectives have embraced the film as a critical turning point in Turkish horror. Today, Şeytan feels like a bridge between imported scares and a future wave of homegrown Islamic horror cinema.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014 — Iran/US)

Ana Lily Amirpour’s black-and-white vampire noir is an achingly cool, part Western, part living graphic novel, part gothic romance. It’s set in the fictional Bad City, a decaying oil town where a lonely vampire girl in a chador glides through the darkness, punishing abusive men and searching for connection.

Sheila Vand’s performance makes the supernaturally strong and fanged protagonist still feel vulnerable and deeply human. Iranian cultural identity meets California indie swagger in a film that embraces genre as a playground for feminist rebellion with one of the greatest soundtracks in recent memory.

In this stylish, romantic and bone-dry witty film, the scares are sparse but powerful when they come. It’s the kind of horror that invites you to luxuriate in the shadows with it. Amirpour’s follow-up films have failed to capture the magic of her debut, but we hope her next, the intriguingly titled Basketful of Heads, currently in pre-production, will be a return to this exquisite form.

Under the Shadow (2016 — Iran/UK)

Set during the Iran-Iraq war, Babak Anvari’s debut traps a mother and child in a Tehran apartment as air-raid sirens wail, buildings collapse and a jinn stalks them. The haunting builds through paranoia and silence — the horror of living under surveillance, bombardment, and a system that doubts a woman’s every move.

Narges Rashidi gives a fierce and layered performance as Shideh, whose exhaustion is palpable as she battles these many terrors. While it’s steeped in politics and history, the film’s scares feel universal: the creeping dread that the walls around you aren’t safe and that one cannot truly escape past traumas. Taut, emotional and sharply directed, it remains one of the most acclaimed and singular horrors of the past decade, launching the career of Anvari who continues to deliver fascinating and eerie work.

Munafik (2016 — Malaysia)

Syamsul Yusof’s Munafik is a sincere, spiritual take on possession horror that is rooted in Islamic teaching and Malaysian tradition, rather than Hollywood theatrics (or, in the case of The Conjuring franchise, eulogising literal conmen). Yusof stars as a healer whose own crisis of faith leaves him vulnerable to forces testing his belief. The ruqyah exorcism scenes feel grounded and reverent, giving the film’s spooks intimate stakes that hit you like a punch in the gut when things turn dark.

It became a major hit in south-east Asia and proved audiences were eager for horror that spoke to their specific existential fears. Part supernatural thriller, part moral drama, Munafik shows that a complex understanding of faith can be both a shield and a source of terror, sometimes at the same time.

In Flames (2023 — Pakistan/Canada)

Zarrar Khan’s Karachi-set stunner blends social realism with dread. We aren’t trading in jump scares, but rather the slowburn feeling that something awful is about to happen. After the death of the family patriarch, a medical student and her mother find themselves threatened by predatory men, and by something even darker that feeds on their fear.

Khan shoots the city like a nightmare: streets buzzing, shadows too thick, danger always out of frame. The supernatural doesn’t diminish the real horror of fearing sexual violence; it crystallises it. With festival acclaim and critical praise behind it — and alongside arthouse fare like Joyland, The Glassworker, and Wakhri — In Flames is part of a wave that points to Pakistan as a powerful new voice in edgy global cinema.

The Book of Sijjin and Illiyyin (2025 — Indonesia)

Director Hadrah Daeng Ratu delivers an intriguing dose of Indonesian folk horror that weaves in religious myth via the twin books of sijjin (sins) and illiyyin (good deeds). Her protagonist Yuli’s journey from wounded woman to someone willing to embrace dark forces gives a compelling character study at its core, and actor Yunita Siregar keeps the character believable even in its most chaotic moments.

The production design and practical effects stand out, especially in comparison to the CGI sludge that has taken over much of mainstream horror. And while the film does rely on a somewhat predictable cycle of ritual, revenge and terror, it uncovers deeper and more fascinating themes connected to faith, freedom and moral consequence.

The Elixir (2025 — Indonesia)

The Elixir, which premiered worldwide on Netflix on 23 October as one of its big Halloween releases, follows a family facing a rapidly spreading outbreak of the undead after a mysterious potion corrupts a village. Director Kimo Stamboel, known for stylish and gnarly hits like DreadOut and The Queen of Black Magic, brings sleek genre craft to a story rooted in south-east Asian folklore and complex intergenerational family dynamics.

The movie is both a zombie thriller and a moral reckoning, and also just a grand ole time. It’s the perfect movie to end your horror marathon: new, widely accessible and ready to take out the spooky season with a bite.

Newsletter

Newsletter