In an uncertain world, I am drawn to family gatherings and a place on my grandmother’s sofa

There is so much beauty in the simple act of gathering: the laughter between generations, gossiping, the silence that no one needs to fill, all over several rounds of tea

When my bebe’s (grandmother’s) sister, Khala Adeeba, died earlier this year, my family gathered at bebe’s house every other day. People from our Iraqi community passed by, offering their condolences and grieving with my grandmother. The Qur’an was playing on the TV in the background, and the women of our family made several rounds of tea, bringing the guests kleicha and ka’ak biscuits.

When everyone left my grandma’s, we relaxed a little, the formalities staying at the door where we waved goodbye to guests. We put our feet up, drank more tea, and even laughed.

We have names for different types of gatherings. A ga’ada, which means “sitting”, is usually a casual get-together. An azeema tends to be a more formal and intentional dinner party. A hafla is a party, and then there are the ritual gatherings to honour the deceased or celebrate a birth.

When I was a child, I used to resent being forced to join my mother at her azayim or ga’dat (gatherings). I’d be forced to sit at tables of older women, their voices booming and shaking my small ear drums. Gossip — in a language that at that time was foreign to me — would hover around me, passing between the lips of women. Uncles with pot bellies would kiss my cheeks with their harsh stubble. I would lay down on my mother’s lap and clasp my palms to my ears, close my eyes and try to find respite amid the chaos.

But as I enter my late 20s and journey out of adolescence, I find myself returning to the places where I began. As the world seems more uncertain than I’ve ever experienced it, I am drawn to seeking a place on my mother’s or grandmother’s sofa, to gather with those who share my ancestry, to find belonging among kin. Amid the chaos, I want to be of service in the homes of my loved ones, making tea, clearing up the dishes, contributing to the loud chatter and laughter, moving furniture and buying gifts.

When I joined my mother in Chicago for my second cousin’s wedding last December, I knew almost no one there. But I gladly sat at tables of elder Iraqis, often the only young person involved in the conversation. I felt belonging to something greater than myself. A connection to a web of life. The realisation that these elders need a witness to their stories or risk their experiences being forgotten. By absorbing their anecdotes of life in Iraq and migration, I can carry their memories.

As we prayed, ate and danced together, I began to appreciate these separate expressions that make up a gathering — and all the different types of gatherings for their various purposes.

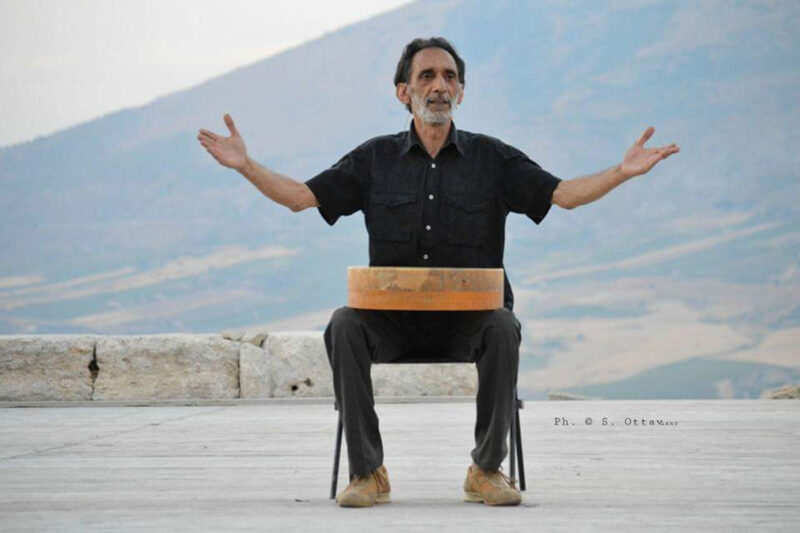

Dance has always been a thread that binds people together. At weddings, haflat and family celebrations, the rhythm of the tabla or the sway of dabke pulls people into a circle where individuality dissolves into collective movement. Unlike conversation, which relies on words, dance communicates through the body, affirming joy, resilience and survival. To dance in community is to remind ourselves that our culture is alive, not just archived in memory.

Gossip is often a key part of these gatherings, too — an essential part of any healthy society. I remember news of various divorces reaching me through the Iraqi grapevine and I would hear rumours of what someone’s husband was accused of. I’d learn which family had large sums of money and how they acquired it, and, of course, who was affiliated with which political party. Gossip has endured for millennia precisely because it sustains cooperation and strengthens community bonds.

Mesopotamians were, apparently, great gossipers. And sitting in a living room of Mesopotamian women today in south-west London, it makes sense to see that continuity alive. The snippets exchanged in quiet corners of the kitchen or around a coffee table create a sense of kinship — for someone to divulge a community secret means they trust you. Or, perhaps, it is that person’s cheeky way of sharing information they feel needs to be heard, but protecting themselves from being the source.

There is so much poetry and beauty in such a profoundly simple act of gathering: there is healing power in the laughter between generations, gossiping, sharing stories, the silences that no one feels the need to fill, the way these gatherings continue for hours into the night, with several rounds of tea made by various family members.

I have found family gatherings a deep source of comfort over the past few years — especially since the genocide in Gaza began, which made many of us seek to lean in closer to our communities. Gatherings are spaces where the community’s values are made manifest, where collective prayer, sharing of a physical space and hospitality, are markers of respect for those from the same blood or background.

In this spirit, I try to never pass up an invitation, whether it be with my blood relatives or my chosen family or friends. Even when I’m feeling tired, antisocial or too busy, I remember that the price of community is a price worth paying.

Newsletter

Newsletter