A House of Dynamite: nuclear thriller shatters the myth of American exceptionalism

Kathryn Bigelow’s latest film is the culmination of a trilogy that examines fear — not of the ‘other’, but of the dark potential of Washington

Director Kathryn Bigelow has spent her career examining the US from the inside. With Oscar-winning The Hurt Locker (2008) and Zero Dark Thirty (2012), and now her latest feature A House of Dynamite (2025), she has built a trilogy examining fear — not of the enemy, but of the dark potential of the city on a hill.

A House of Dynamite, which comes to a global audience on Netflix from 24 October after a limited cinema release, takes on one of the planet’s worst nightmares — nuclear annihilation. One morning, the US government and military learn of a missile on a direct course to destroy Chicago. It will land in under 20 minutes; its origin is not known, nor is there time to evacuate the city.

It is Bigelow’s most experimental film yet, shifting focus from the foreign to the domestic; statesmen trapped inside the circuitry of global panic.

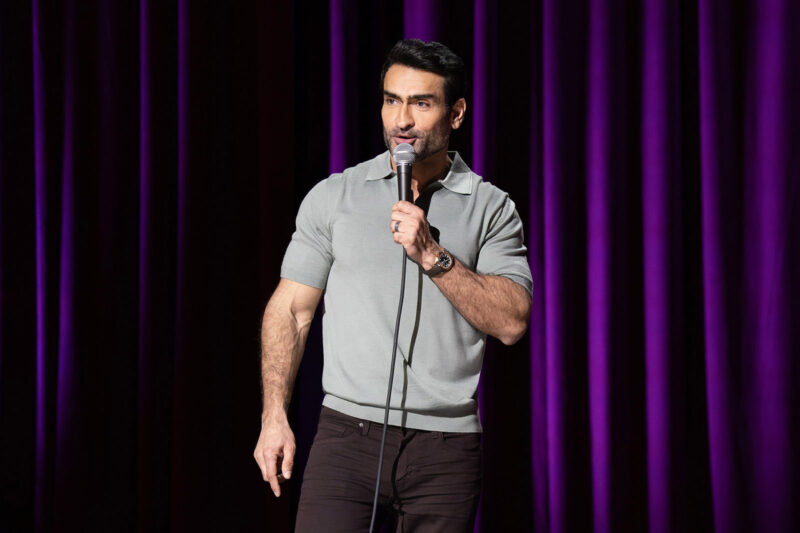

The ensemble is uniformly excellent. Idris Elba is the president, the elegant Rebecca Ferguson is the officer running the situation room, and Jared Harris is Shakespearean as the secretary of defence. Anthony Ramos plays an army major barely holding it together while running the missile interception mission.

A House of Dynamite feels like the conclusion to a series of works that Bigelow has been devoting herself to for decades. Each film marks a distinct geopolitical mood: Bush’s intoxicated militancy, Obama’s attempted omniscience, and Biden’s failing. Together they trace the slow decomposition of the national myth of American exceptionalism.

The thriller is a nauseatingly tense pressure valve, as we see the same question asked of each individual’s role in a system responsible for perpetuating and preventing global annihilation. The fact that the missile’s origin remains unconfirmed is crucial. For once, the “enemy” is invisible and unassignable.

The Middle East isn’t explicitly to blame for the imminent disaster, but the legacy of an America that thought it could crush the world to its will feels ever-present. This ambiguity of the source of the attack exposes the hollowness of a narrative where politics and Hollywood have long relied on Muslim villainy to sustain American nationalism.

Throughout this trilogy, Bigelow makes tactile the global anxiety felt by those outside of the US’s borders. Her characters are all tasked with preserving control in a world that keeps slipping from their grip. In an era seemingly defined by a never-ending “war on terror”, fear of immigrants and encroaching Islam, Bigelow’s insights have continued to hold the complexity and cruelty of her country in one hand.

In The Hurt Locker, Bigelow turns Baghdad into a whirlwind of adrenaline and sand, where surviving the day becomes the only ideology left standing. Sergeant William James (Jeremy Renner) defuses bombs motivated largely to avoid his own death, because it’s the only thing that still feels real. This isn’t triumphalist military cinema as even our “heroes” are untethered from a land they have no connection to, or business being in.

For all its style and ethical complexity, The Hurt Locker is also a study in dehumanisation. Iraqi civilians appear only at the edges, their interior lives remain inaccessible. Bigelow’s Iraq is curiously opaque, mirroring the American soldiers’ and public’s disassociation.

In doing so, she visualises a central paradox of Bush-era geopolitics: a country obsessed with the Middle East but incapable of seeing it clearly. The war’s moral void becomes a visual one, with Arabs present but voiceless — a mirror in which the American soldier confronts only what this war is doing to himself.

With Zero Dark Thirty, Bigelow’s shift in tone reflects the evolution into the Obama era, where warfare became a science — methodical, data-driven. Jessica Chastain’s Maya embodies this new technocratic consciousness: a woman who turns a national obsession with vengeance for 9/11 into a brutal region-wide policy that contributed to an estimated 4.5 million deaths.

The hunt for Bin Laden becomes a cold, relentless ritual. Bigelow’s camera is surgical, treating each operation as a procedural inhuman exercise. Even the torture scenes feel bureaucratic; violence transforms into paperwork.

Here, Muslims are no longer distant civilians, but the objects of interrogation and targets. It’s easy to accuse Bigelow of profiting from the dehumanisation she depicts. She seems convinced of her protagonist’s sincere belief that a mass murderer should be tracked down at all costs. But her gaze is not uncritical. We are made to feel the coldness of a system that can observe endlessly, but rarely understand.

Rather than being a film about war, A House of Dynamite is about the fear of the long-simmering consequences of many wars. It humanises the people at the heart of the race to stop armageddon, while leaving the viewer furious at the status quo they are part of.

In it, Bigelow makes literal what her earlier films implied: the entire architecture of American security is built on panic. The title is a perfect metaphor for a republic that spent its enormous power to build a structure wired to explode.

The trilogy forms a strange triptych of empire and orientalism. Bigelow turns our geopolitical anxiety into thrills, only to let you linger with the terrible truths they spoke.

A House of Dynamite is in UK cinemas now and on Netflix globally from 24 October.

Newsletter

Newsletter