Arab artists to look out for at Frieze London

We select the galleries from the south-west Asia and north Africa region showing at this year’s art fair in the capital

More than 280 galleries and 45 countries constitute this year’s offering at Frieze London, which returns to Regent’s Park between 15 and 19 October. Among those represented are a selection from the south-west Asia and north Africa (Swana) region, including those operating in Egypt, Lebanon, Tunisia and Saudi Arabia. Iranian artist Abdollah Nafisi’s sculpture, Neighbours, is currently installed as part of Frieze Sculpture, a free display in the park preceding Frieze London and Frieze Masters.

Ahead of the art fair we speak to some of the galleries and artists whose new work probes childhood myths, the afterlives of public art, environmental futures and material histories.

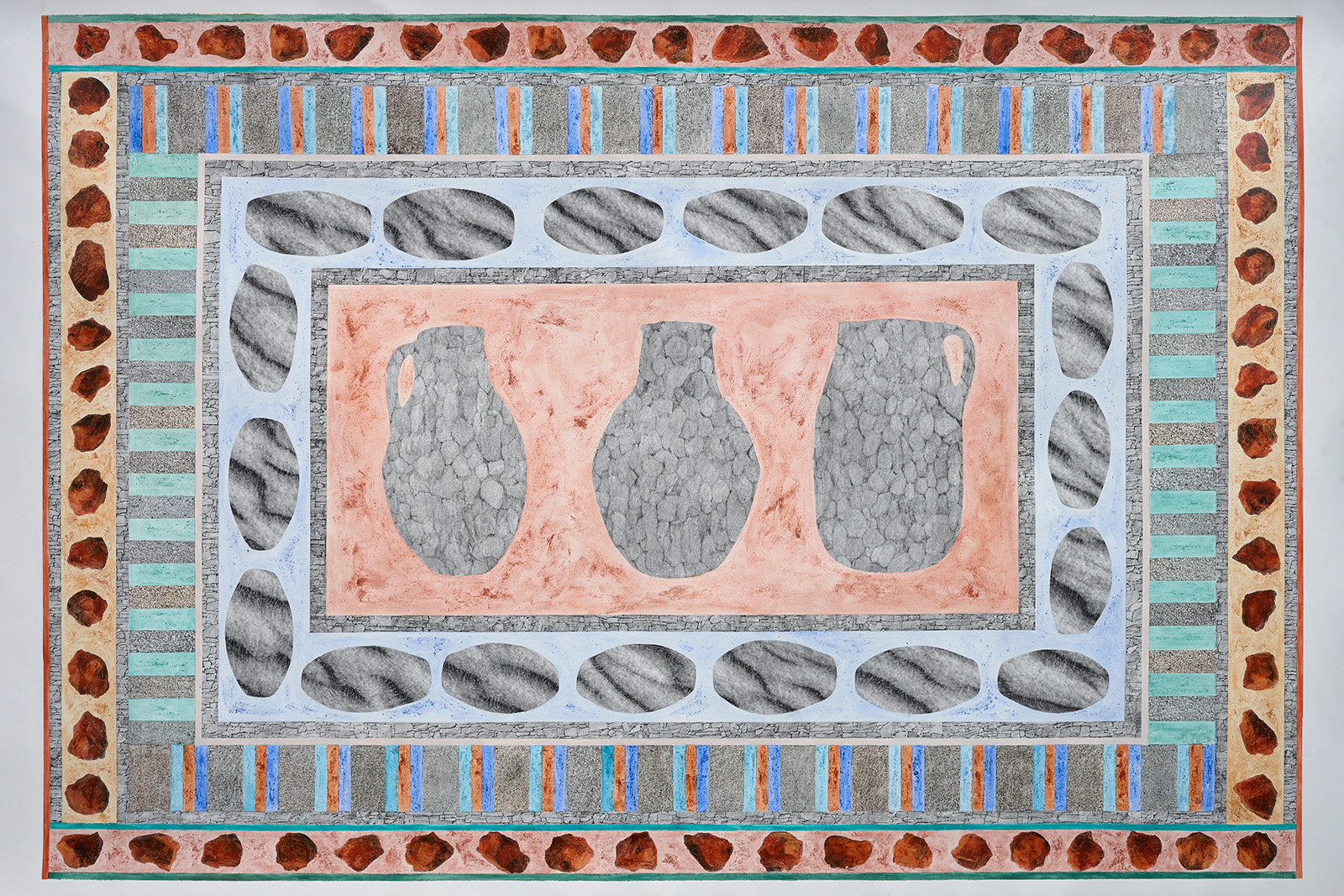

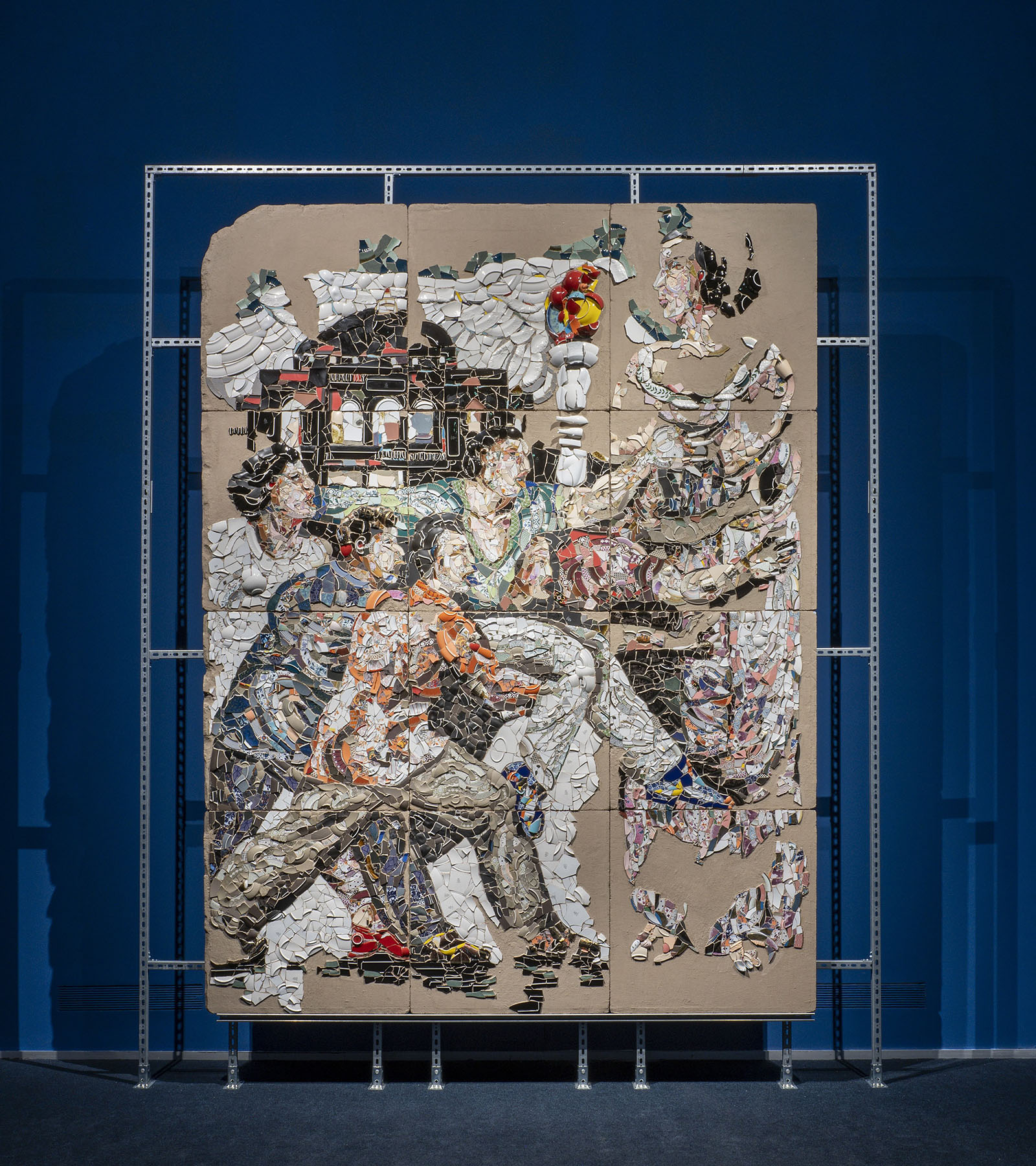

Yasmine El Meleegy, Gypsum Gallery, Cairo

In 2018, Cairo-based artist Yasmine El Meleegy began an ongoing project inspired by the work of the Egyptian sculptor and painter Fathy Mahmoud, spanning a series of letters that she wrote to the deceased artist as a way of understanding his little-archived legacy.

Mahmoud was frequently commissioned during the Gamal Abdel Nasser era to create monumental public art — including murals at Cairo University and the Alexandria port — but he became better known for his eponymous ceramics factory. “By chance, I found a porcelain sculpture signed by Fathy Mahmoud in my mother’s collection,” El Meleegy tells me, a discovery that set off an interest in the artist’s oeuvre, and the politics of mass-production. “I was asking myself, should we still interact with his tableware sets as pieces of art?”

El Meleegy, who works across sculpture, installation and site-specific interventions, will be showing two wall sculptures at Frieze London that reappropriate Mahmoud’s murals at the Alexandria port. Using shards from porcelain dinnerware on Marmox board, El Meleegy creates a collage-like mosaic of the port workers that Mahmoud had once immortalised. Taking up to three months to complete each wall piece, the process, El Meleegy explains, is “labour-intensive”. The result is an altogether new composition that deconstructs the nationalist meanings of the original murals.

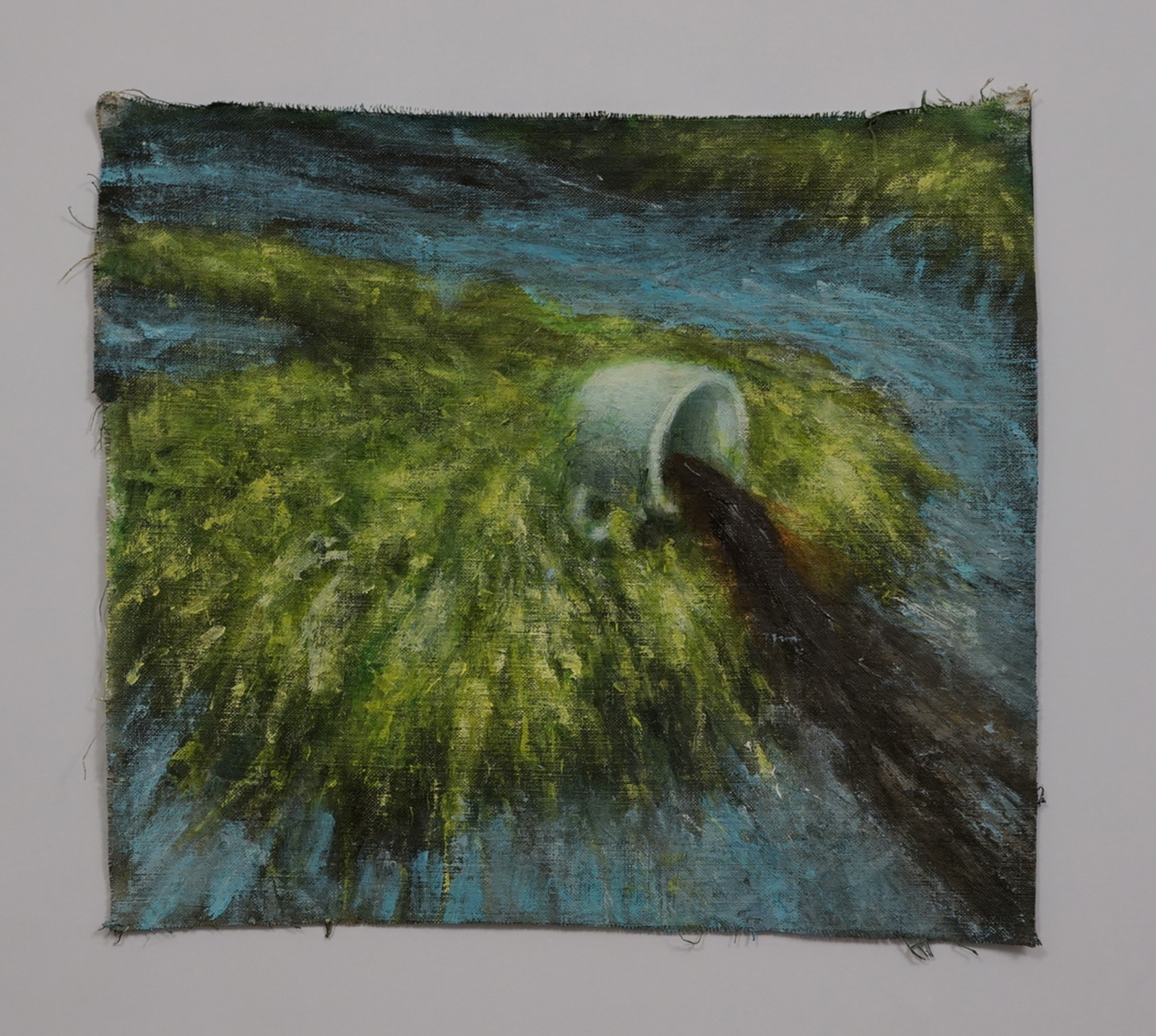

Marianne Fahmy, Gypsum Gallery, Cairo

“I’m based in Alexandria, my home town, where potential floods are anticipated because of rising sea levels,” says artist Marianne Fahmy. In Alexandrian Desert Dreams, a pair of monk’s cloth tapestries painted in soft pastels and completed with hand-embroidered thread and yarn, Fahmy depicts leisurely scenes of Alexandrians gathering around bodies of water and the city’s ancient cisterns. Surrounding them is an arid landscape, reflecting an imagined scenario where displaced residents, as climate refugees, relocate inland to satellite cities in the desert.

“What would happen to the society that would flee the city? Where and how would they exist?” Fahmy asks. “It’s a very peaceful image, when you look at it,” she says, explaining that she drew from archival photographs of people at Alexandrian beaches, including vintage 1960s postcards of the city. “But when you see it in the context of the environment itself, you then see what the [tapestries] are really about.”

In addition to these new works, Fahmy, whose practice spans photography, sculpture and mixed media, will be showing the film Laws of Ruins (2024) at the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London, as part of the Frieze x ICA Artists’ Film Programme.

The film was shot inside one of Alexandria’s water cisterns, as well as at an archaeological site in Sardinia that once housed an advanced water system, illustrating the Hellenistic connection between the two places. In it, she explores the aftermath of environmental devastation. Fahmy’s hope is to preserve a “collective memory” of the local cisterns’ existence.

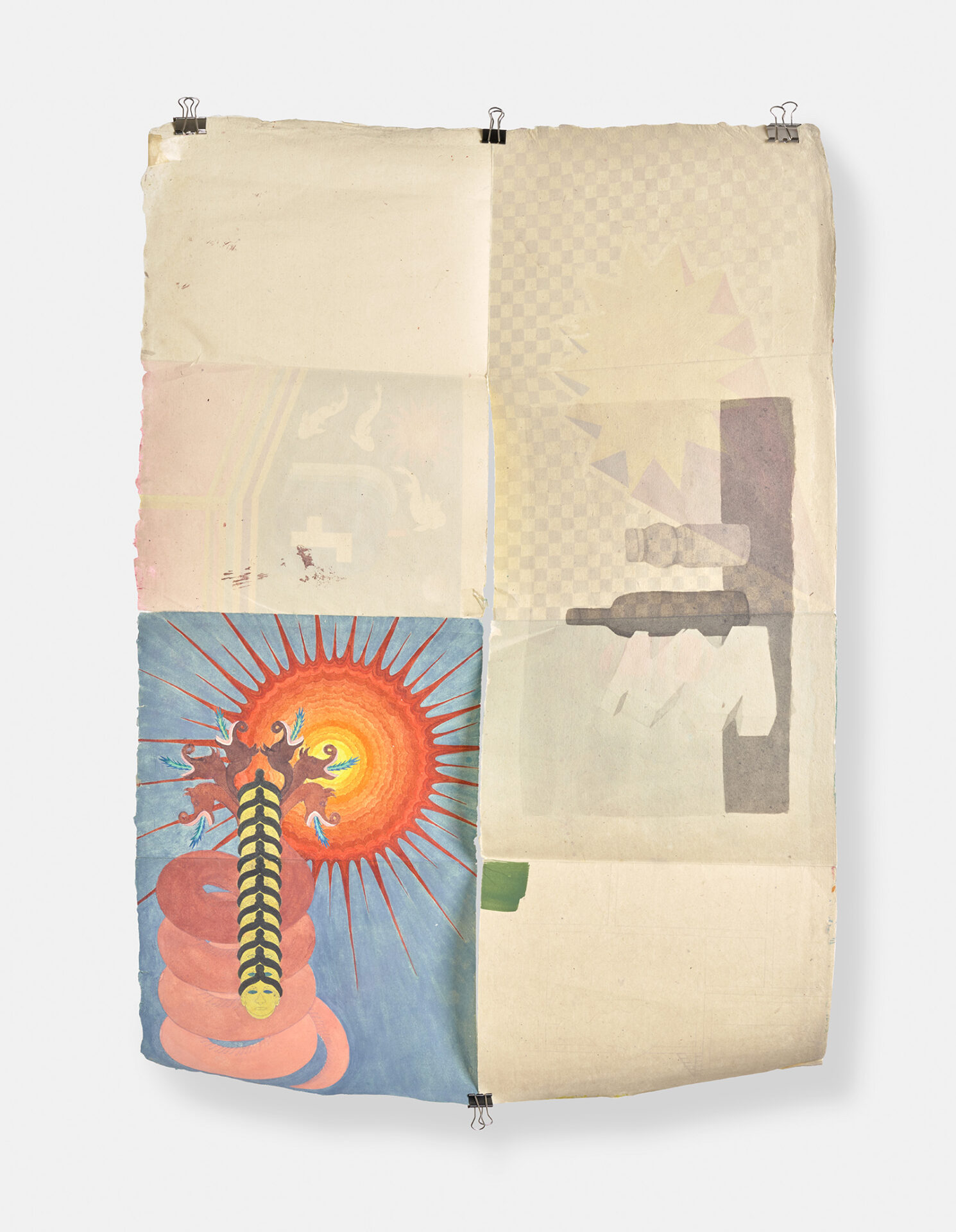

Omar Fakhoury, Marfa’ Projects, Beirut

Superstitions and folkloric beliefs inform the new work of Lebanese artist Omar Fakhoury, who will be presenting paintings and sculptures as part of his series Touch Wood. Growing out of previous works, Touch Wood draws on anecdotes he heard as a child.

“Whenever it was raining and the sun came out, people used to say, chameleons are getting married,” he recalls. “Or, if a man passes under a rainbow, he would be transformed into a woman.” Transmitting these childhood stories into visual representations has been the focus of the series, which includes small-scale acrylic-on-linen paintings, two larger works and various sculptures, capturing both the absurd and the mystical elements of the myths.

Often, anecdotes were gathered from people around Fakhoury. “My barber’s mother-in-law told him not to bring a dog into the house, because angels would stop coming,” he says — a story that resulted in a painting of a labrador angrily peering down at two dancing angels. Elsewhere, Fakhoury paints a knife and a high-heeled shoe wedged under a stained mattress, referencing a popular method to ward off nightmares.

Previous works have often centred around Beirut, where Fakhoury is based, including a series on political monuments and depictions of military checkpoints. “There’s always this back and forth between yourself and where you live, and you always have to respond to big issues like war,” he says. While he was working on his previous series The Forest, the bombardment of Gaza was ongoing. “You start asking yourself, why paint a flower now?”

ATHR Gallery, Saudi Arabia

ATHR Gallery was founded in 2009 in Jeddah. Its presentation at Frieze this year comprises new works by Saudi Arabian artists Daniah Alsaleh and Basmah Felemban. Alsaleh draws from her research on archaeological discoveries in the Nabataean city of AlUla, while Felemban’s approach is futuristic, rooted in imagined ecological scenarios depicting the presence of marine species in unlikely contexts.

Crushing the mineral carnelian into a ground-down pigment, Alsaleh paints contemporary views of AlUla in her Stone Palette series. In a multimedia installation that uses photo transfer, watercolour, acrylic paint, and seven videos played on a loop, she brings to life the ghostly traces of a distant civilisation through a focus on the Nabataean woman Hinat.

Felemban works across Islamic art and digital and graphic design. She creates ballpen and gouache renderings in Coral Sprite Leaf (2024) and Monsters in Still Places Zine (2024), exploring coastlines and the desert — evolving and mysterious natural landscapes that provide an entry-point to her speculative worlds.

“We envisioned our Frieze London booth as a conversation across time,” Lacy Schutz, ATHR Gallery’s director says. “Alsaleh’s work anchors us in the deep histories and material memory of the region, while Felemban’s practice pushes forward into speculative world-building shaped by language, data and ecology. Their dialogue reflects a Saudi art scene attuned to both its roots and its horizons — a landscape that is never static.”

Schutz notes that the presence of galleries and artists from the region has become both visible and influential over the years. “In particular, contemporary art from the Gulf now holds a firm place in a global conversation once dominated by western narratives,” she adds. “This shift goes far beyond representation. What began as occasional participation has grown into an embedded presence — shaping the fair’s discourse around identity, colonial legacies, migration and cultural assumptions.”

Newsletter

Newsletter