The teachers bringing marginalised stories into schools

As a new term begins, we meet educators who are highlighting Muslim histories and helping pupils become critical thinkers

In history classes across the country, schoolchildren are told the stories of Henry VIII and his wives, the trenches of the first world war and the era of rationing when British forces fought the Nazis. A tidy chronological story of our nation with a beginning, a middle and an end. What they typically learn less about are the scholars of Baghdad, the merchants of the Indian Ocean or the Muslim soldiers who fought for Britain in both those wars.

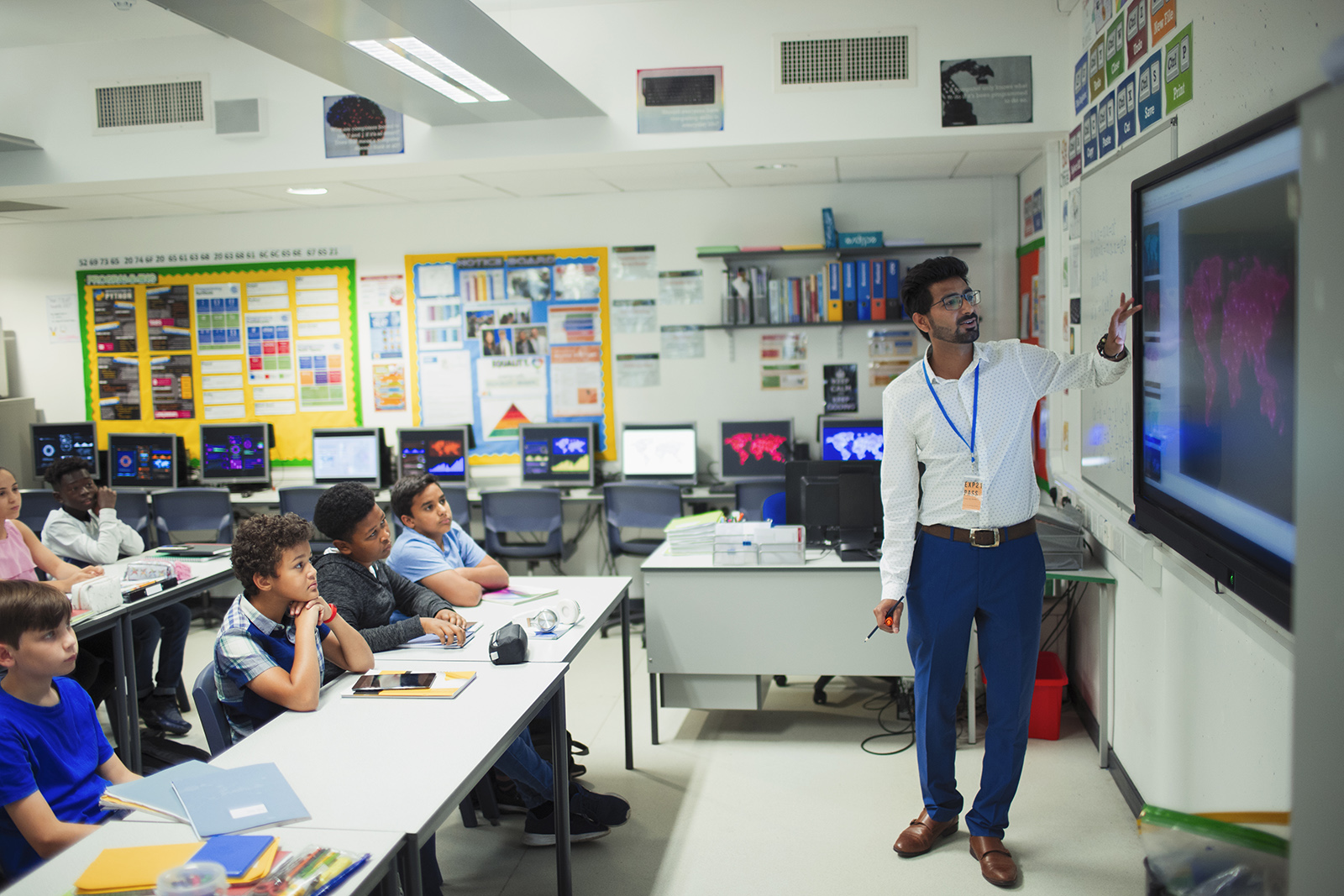

Those histories lie hidden in the margins of the syllabus. However, some teachers are trying to change that by making additions that teach students to see minority communities not as footnotes, but as inseparable from the more commonly received narratives. That work follows years of campaigning from activists and educators to diversify the syllabus for all ages, demands that are being addressed in the government’s current curriculum review.

This year’s autumn term has opened against a backdrop of rising anti-migrant sentiment, a stark reminder that the histories children are exposed to — or denied — matter now.

“Global histories are always essential,” says Afia Chaudhry, a teacher based in London. “To make clear that inclusion is not tokenism, we need to frame history carefully. It is important we continue to teach these stories now, not as a culture war gesture, but as accuracy.”

A graduate of Soas University of London, Chaudhry teaches history at an academy school in north London. She is also head of education at the Hussain Foundation and a doctoral researcher at Oxford.

For her, the point is not to bolt a few exotic extras onto a tired lesson plan, but to put Britain back into the conversation it has always had with the wider world. “I am a strong advocate for national history taught well, but not at the expense of the global contexts that shaped it,” she says.

This doesn’t mean straying from the curriculum. Her school has built “shared schemes that thread Islamic civilisations, the Indian Ocean world and postwar migration through key stage 3 [ages 11-14]. The method is plain: interrogate the curriculum map, find the hinge points where the wider world already meets the enquiry and teach the narrative there. Not as a favour, but because that is where the history sits.”

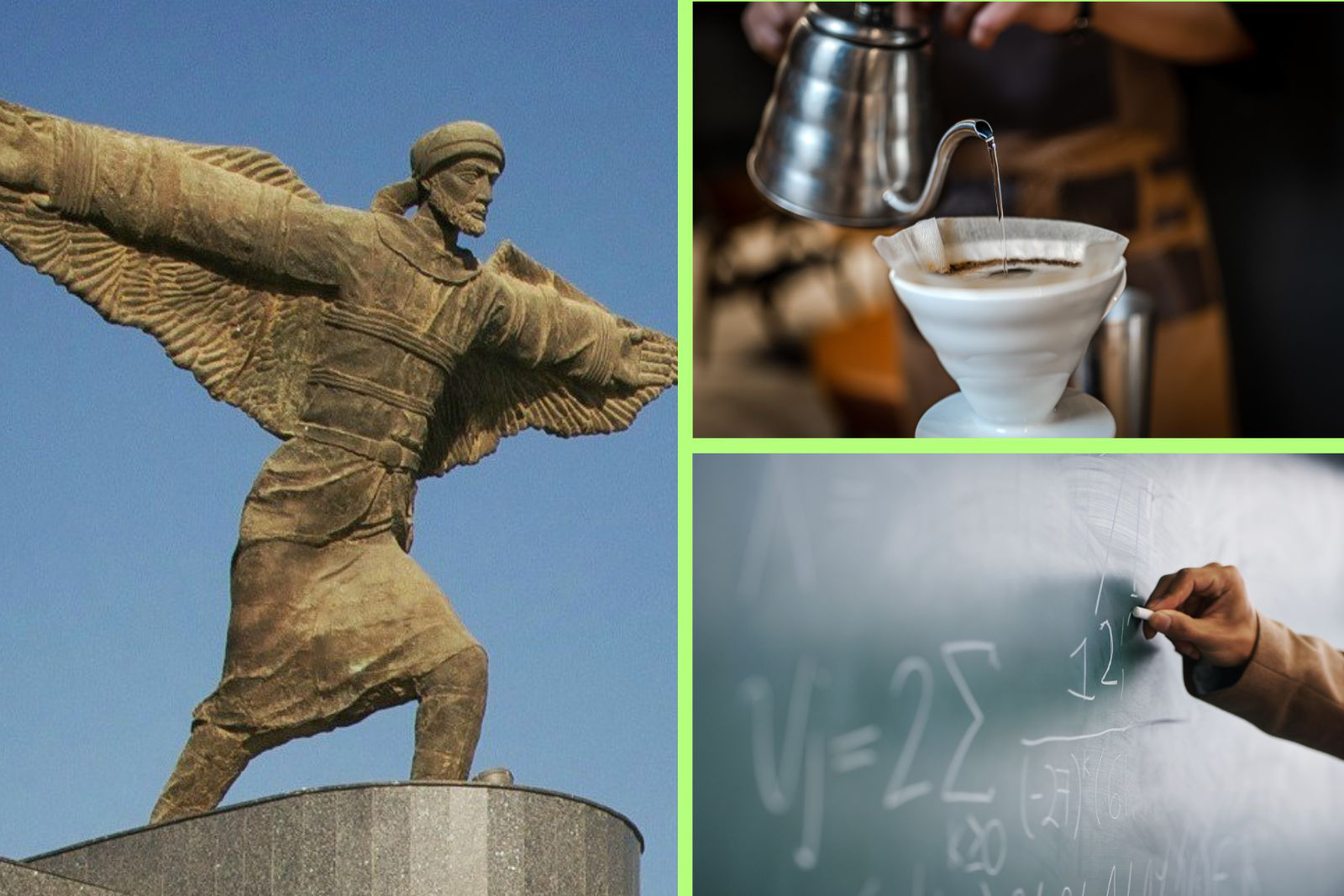

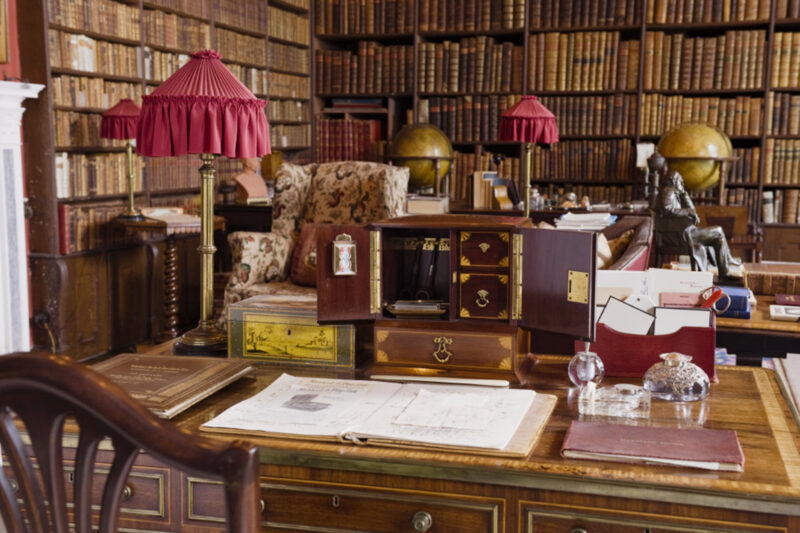

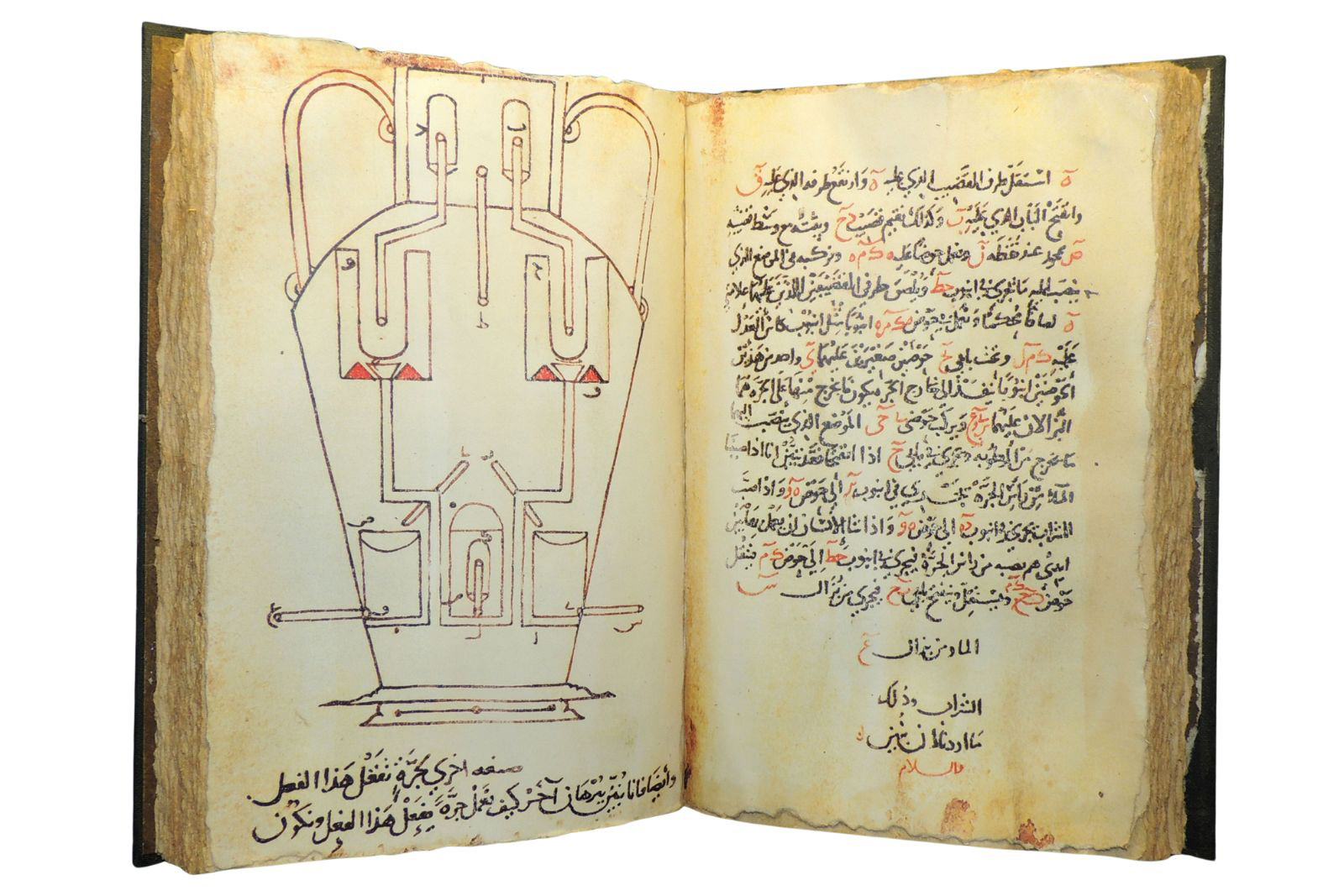

Chaudhry’s pupils don’t just march through the Tudors and Stuarts. In Year 7 they are in eighth-century Baghdad, reading about the House of Wisdom, the mathematician al-Khwarizmi and inventor al-Jazari, then asked to weigh up what counts as good evidence for how knowledge was built and traded. By Year 8 they’ve reached Al-Andalus, using historical texts to judge just how peaceful the region was.

Later, they track how Ottoman diplomacy and Mughal textiles seeped into Europe and how Muslim labourers kept armies moving and factories running during the wars, leaving behind letters and photographs as testimony.

“Students genuinely lean in. Lessons are framed as competing accounts where pupils challenge claims and practice reasoned disagreement. The point isn’t to tell them what to think, but there are also objective truths,” says Chaudhry.

“Supporting student’s historical development also encompasses teaching certain moral realities and weighing evidence without an attempt at eliciting emotion. History is about judgment, too.”

Zameer Hussain is a secondary religious education teacher and department head in Essex who specialises in Shi’a Islam. Hussain has written guides and programmes for fellow teachers on how to teach the Sunni-Shia split and volunteers with Parallel Histories, a UK charity that supports schools in teaching contested and complex histories through multiple perspectives.

“When I teach Islam I always start with pre-Islamic Arabia,” he says. “Students need to see that Islam wasn’t born in a vacuum, but shaped by a world of tribal loyalties, trade and poetry.” Hussain frames it as a history lesson first, a theology lesson second.

“I make sure pupils understand timelines, when Islam emerged in relation to Jesus, what events shaped Muhammad’s worldview, how the Sunni-Shia split changed everything. It’s not just names and dates. It’s about how worldviews are formed.” Even Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, the Pakistani qawwali singer, becomes evidence in understanding how music can show us how faith can be felt and interpreted.

“My aim is to ensure that Muslim histories are not presented as a singular entity, but through multiple perspectives, so students grasp the diversity of voices within Islam,” he adds.

The difference from mainstream or western accounts, Hussain argues, lies in honesty. “Students should know that every historian writes with an angle. A Muslim historian will write differently to a non-Muslim one. And pupils need to be aware of their own worldview too: a Muslim child will presuppose Muhammad as a prophet, a non-Muslim may see him as another human. That awareness of the difference makes them critical thinkers.”

Meanwhile, Burhana Islam, Manchester-based secondary teacher and author of Amazing Muslims Who Changed the World, has spent years coaxing history out of textbooks and into the imaginations of her students. “I introduced the stories of explorers, rulers and inventors, got the whole class excited about them, and then at the end added: ‘They’re also Muslim, did you know?’”

She recalls how in the lesson, two Muslim pupils, barely acquainted, connected over the story and high-fived across the classroom. “They were thrilled, their eyes were lit up and they talked about it beyond the lesson too despite not knowing very much about each other.”

Across different subjects, year groups and approaches, these teachers are quietly redrawing the curriculum and insisting that Muslim and minority histories are integral. There’s the hope that students will leave with a sense that the world — and Britain’s place within it — is more complex and more connected than many would have you believe.

Newsletter

Newsletter