Why Starmer may have just months to win over anxious backbenchers

The prime minister survived Trump’s visit. But a minority of Labour MPs are whispering about a possible successor if he can’t deliver domestically

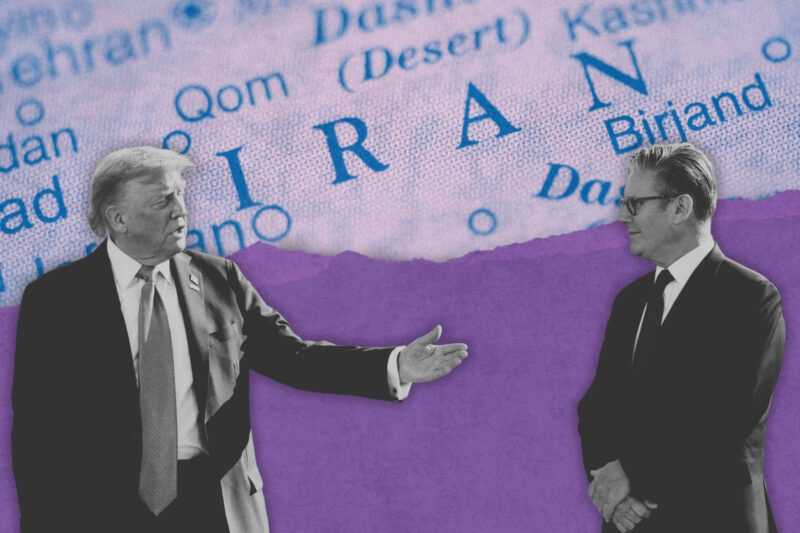

The pomp and ceremony of a state visit can often feel slightly surreal. The red carpets, golden carriage and glittering banquets are the kind of pageantry that feels more like theatre than politics. But beneath the ceremonial niceties lies a delicate balancing act that requires months of careful planning. With the ever unpredictable Donald Trump in the White House, the stakes of the past few days have been even higher.

For Keir Starmer, this week’s state visit was far more than a diplomatic ritual. The dinner and the toasts were the easy part: the real jeopardy came at the joint press conference where the prime minister stood alongside the US president knowing that he would have to navigate their policy differences while avoiding a public falling out. After the bruising few weeks Starmer has endured at home, a disastrous press conference was the last thing he needed.

On Gaza and Ukraine in particular, London and Washington have diverged sharply. The UK’s stated ambition to recognise Palestinian statehood is anathema to Trump, who does not take kindly to being contradicted in public.

Yet in the end it passed with little incident. Trump expressed his disagreement on Palestinian recognition, but did so with a grin and even a jocular slap on Starmer’s back when the PM called Hamas a terrorist organisation. And on the diplomatically explosive subject of Peter Mandelson’s dismissal as UK ambassador to Washington after the extent of his links to Jeffrey Epstein were made public, Trump was almost uncharacteristically reserved. He offered a few words and promptly deferred to his host.

That restraint in itself was notable. Trump is not known for letting awkward questions pass him by but there had been briefings ahead of the visit that he would go a little more softly than usual, aware that Starmer was going through a rough period.

The optics of these moments matter deeply for world leaders. I’ve accompanied prime ministers on similar trips and visits in the past and have seen their teams agonise over every detail. These visits are supposed to allow leaders to project strength on the world stage, while their officials build the working relationships that sustain alliances behind closed doors.

Behind the scenes, we are told the two men spent nearly an hour in private discussion. They talked about Gaza and Ukraine at length, but neither shifted their positions. There are limits, after all, to how much sway any foreign leader has over Donald Trump.

For Starmer, the absence of calamity was a relief given the bruising he has taken in recent weeks. Since the summer he has been rocked by three high-profile scandal forced exits: first his deputy prime minister, over not paying the right amount of stamp duty; then Mandelson over his Epstein ties; and finally his director of strategy, after explicit and deeply offensive messages about Diane Abbott that came to light because of my reporting for ITV News.

Each departure has weakened him, fuelling whispers about his leadership. That discussion is no longer confined to the corridors in Westminster.

I’m told several Labour backbenchers have alerted their chief whip that they have lost confidence in Starmer’s leadership, and a number of MPs — some of whom only a few weeks ago were junior ministers — have told me that they are waiting to see if Starmer can reverse Labour’s polling by Christmas. The fear among some, with local elections coming in May, is that a narrative of decline is starting to coalesce around the party.

“Once you’re behind in the polls and then you do badly in local elections, the public just start to think you aren’t fit to govern. That’s hard to shift,” one told me earlier this week. The MPs I have spoken to would rather replace the leader than have that. They are very much in the minority at the moment but, once these conversations start happening in Westminster, they can snowball very quickly.

The name that keeps surfacing as an alternative is Andy Burnham. The Manchester mayor has twice run for Labour leadership before and has never disguised his ambition. When I pressed him a year ago on whether he would want the job, he replied, with a smile, that there was “no vacancy” — not exactly a denial.

He remains popular among the MPs that I talk to and polling suggests the public believe he is the Labour politician most likely to do a good job in Number 10. In recent weeks, Westminster has buzzed with rumours that a sitting Manchester MP might step aside to open the path for Burnham’s return to parliament. I was also told that meetings had taken place between some MPs to discuss the potential logistics of such a move — enough to send a chill down Starmer’s team’s spine.

A deadline, whispered or otherwise, is a dangerous thing in politics. It concentrates minds and gives would-be challengers a calendar to plan around. With Labour conference coming soon, then an upcoming budget that is expected to include some pretty difficult decisions, there isn’t much time before that Christmas deadline. Only 14 months after delivering Labour’s biggest majority in 27 years, the prime minister’s position is the most under-the- spotlight it has been since he got the keys to Number 10.

Shehab Khan is an award-winning presenter and political correspondent for ITV News.

Newsletter

Newsletter