The Persian engineering system that could save European cities from extreme heat

Seville has revived the ancient qanat technique, which can reduce ground temperatures by up to 10C

This summer, Spain suffered its most intense heatwave on record. As firefighters battled devastating wildfires in the country’s north and west, the State Meteorological Agency (Aemet) showed an average temperature 4.6C higher than expected and issued a stark warning that extreme heat is set to be the new normal. In Seville, where temperatures are predicted to regularly exceed 50°C in future summers while annual rainfall will fall by 20%, a team of local engineers has turned to ancient Persia for help.

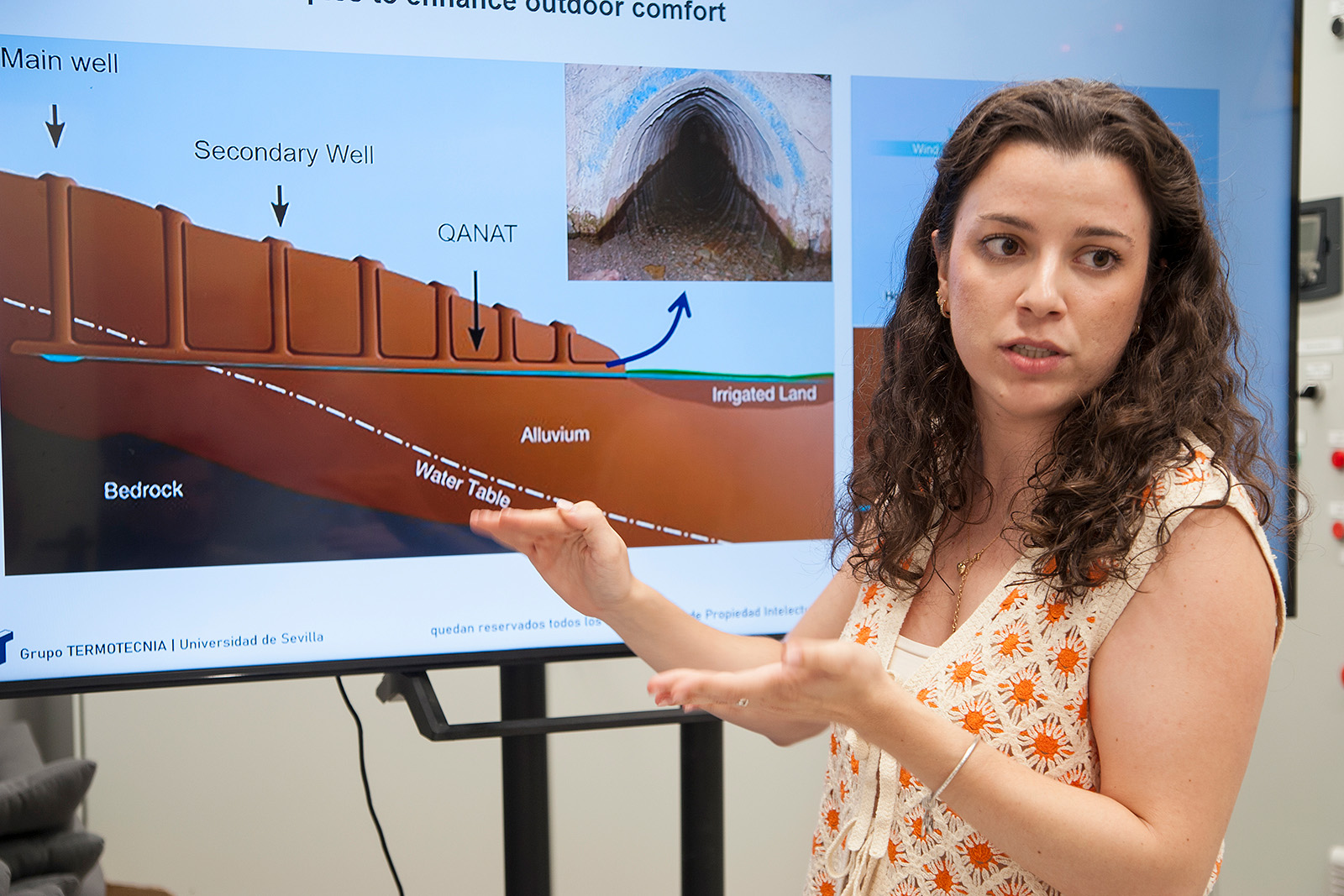

Around 3,000 years ago, Persian farmers developed the qanat technique. Using an underground system of canals installed 20 to 200 metres below the desert surface, slight slopes employed gravity to carry cooling water to irrigate soil, lower ambient temperatures and provide drinking water to animals in arid regions. The city of Yazd in Iran is among the best known examples of this technique and was declared a Unesco World Heritage Site in 2017.

At Cartuja Qanat in Seville, a team that includes the city council, public water services and the Spanish National Research Council is supporting academics from the University of Seville’s Thermotechnics Group to adapt this technology for modern use. Two qanats have been installed on the site of the 1992 Seville Expo over an area the size of two football pitches at a cost of €5m. Solar-powered pumps propel cooled water to the surface during the day, reducing the ground temperature by up to 10C. The water is then naturally re-cooled as temperatures drop overnight.

“We have modernised the technique by integrating rainwater and electricity generated from solar panels. The entire project is therefore completely self-sufficient without relying on energy-intensive technologies,” explained María de la Paz Montero Gutiérrez, a researcher on the project. “[Extreme heat is] our new reality. We don’t have time anymore, we have to adapt.”

Servando Álvarez Domínguez, who directs the Cartuja team, believes the technique could be used to help sweltering cities all over the world. “What works in Seville could work in any other city. Imagine what we could do in places that are also suffering from the heat, but to a lesser extent,” he said. “Everywhere there are buildings or public spaces that require air conditioning and that could support the implementation of this very efficient technique.”

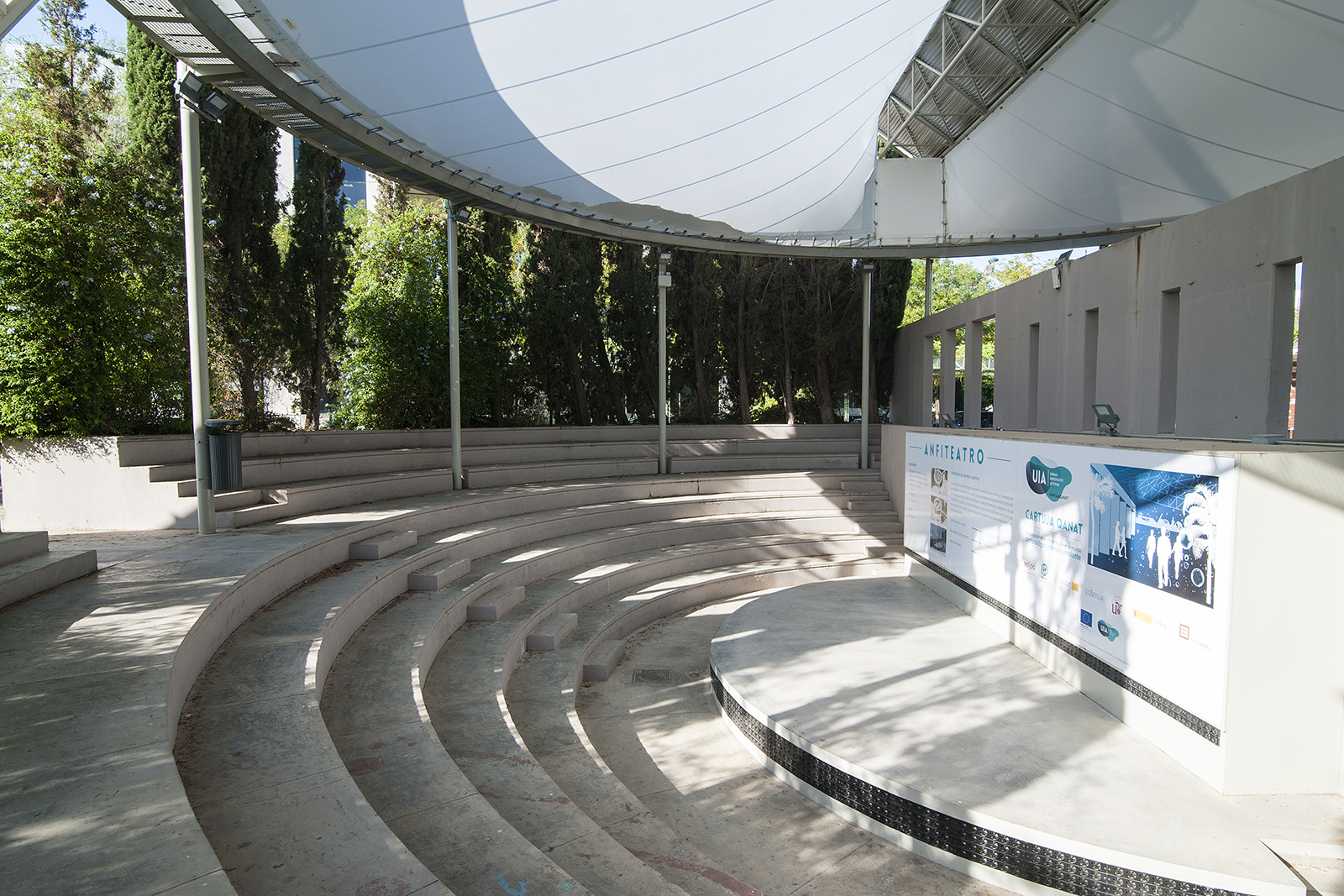

Since its installation in 2021, Cartuja Qanat has become an oasis. Local workers come to refresh during breaks or to play sports. A nearby amphitheatre has also been restored and renovated to benefit from the same technique using suspended channels transporting cooled water.

“If you come here in the middle of the agora, you can feel fresh air and breathe normally, while outside it’s also impossible during afternoons. This model is truly proof that sustainable solutions exist,” Gutiérrez said, adding that vegetation growing on the building’s interior walls, painting external walls white and the orientation of the building’s entrance doors also help to cool the space.

José Sánchez Ramos, professor in energy engineering at the University of Seville, cautions that a challenge will be convincing architects and engineers that the system is worth the additional expenditure — Ramos estimates the project costs the local municipality around €10,000 a year to maintain. “It is not so easy and requires additional costs, from the first investment to the operation and maintenance,” he admitted.

The city of Seville recently won a competition between Spanish cities for its work on climate transition. At Cartuja Qanat, researchers hope the symbolic prize will give their project a boost and encourage other cities to embrace this ancient, green and potentially life-saving technology.

Newsletter

Newsletter