Documentary chronicling a century-old nomadic journey through Persia gets a new score

Iranian composer Peyman Yazdanian is set to perform a live improvised soundtrack to Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life

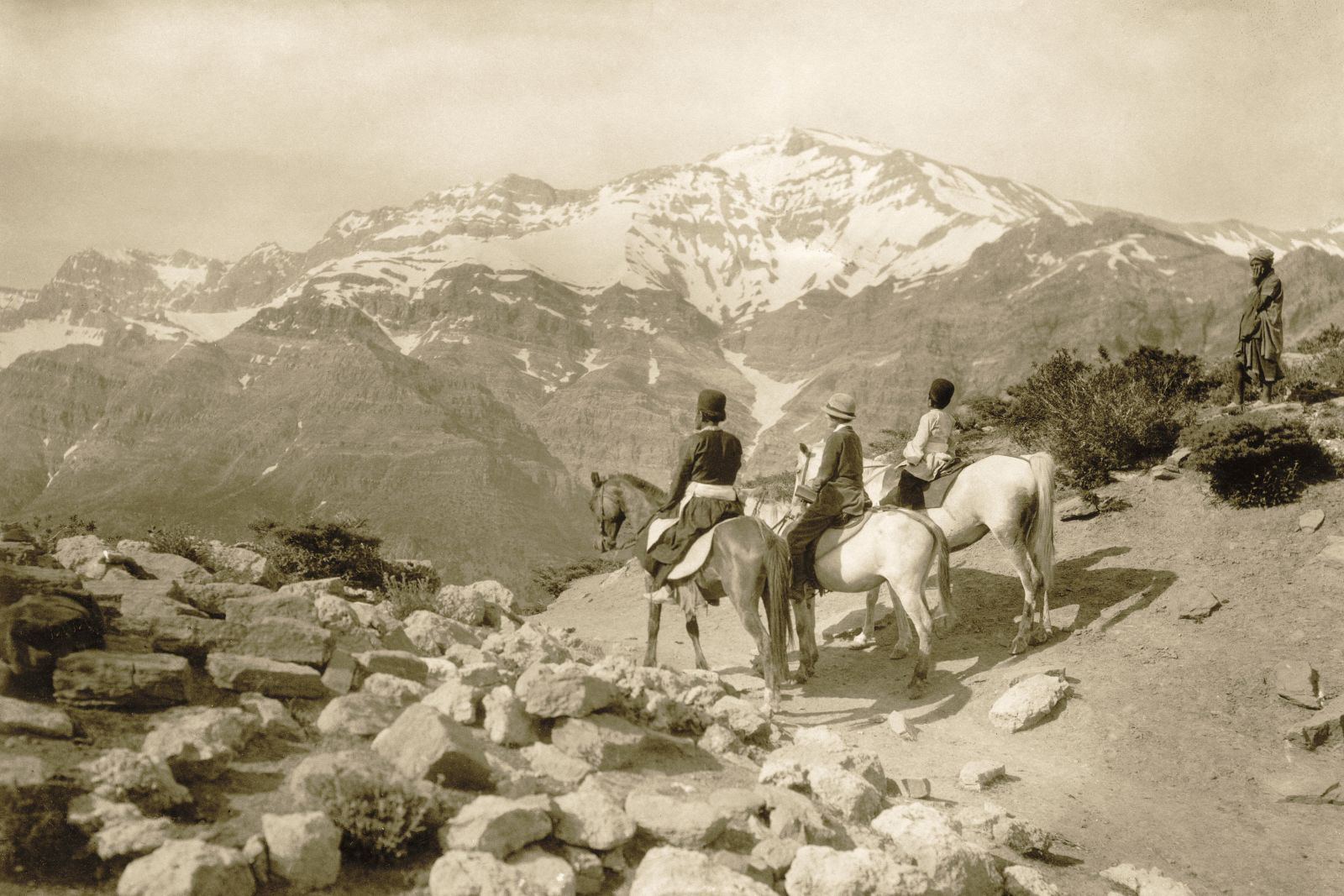

In 1925, 50,000 members of the Persian Bakhtiari tribe set out on a vital journey. Over the course of several weeks, they travelled eastwards from what was then the arid desertscape of Ankara in Turkey, walking barefoot through the snowy Zagros mountains and using makeshift rafts to cross the fast-flowing river Karun to finally reach the verdant grasslands of modern-day western Iran.

Alongside the tribespeople and their livestock were film-makers Merian C Cooper and Ernest B Schoedsack, who documented the perilous trek to produce what would become one of cinema’s earliest silent documentaries, Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life.

A pioneering example of ethnographic filmmaking and a predecessor to Cooper and Schoedsack’s future cinema success with King Kong, Grass is now being remastered and presented with a new score written by Iranian composer Peyman Yazdanian, a century on from its initial release. On 19 September, Yazdanian will be performing his score alongside a screening of the film at Kings Place in central London.

“It’s such a shocking and absorbing film, it doesn’t feel 100 years old at all when you watch it,” Yazdanian says. “The first time I did, it was like seeing an old family photo album of mine — all these Persian faces who are my ancestors. The only issue was the score, which contributes so much to a silent film but in the version I watched it felt so disturbing and orientalist, I had to turn it off and continue in total silence. I decided to write something entirely different.”

In the century since the film’s release, several scores have been written to accompany its dramatic visuals. The original version was the work of composer Hugo Riesenfeld. Although no record of it exists today, it is likely to have sounded similar to the grandiose orchestral epics he wrote for celebrated directors such as Cecil B DeMille and DW Griffith.

While Yazdanian listened to Patrick Holcomb’s 2021 score for the film, which uses western classical orchestration and flashes of dulcimer that swell in moments of tension. “It all played like non-Iranian ‘oriental’ music, which didn’t fit the specificity of the people and the culture that the film is showing,” Yazdanian says. “When you score something silent, the music has to tell the story without overtaking or subsuming it. It has to accompany your feeling and if it sounds off, the images will begin to feel inauthentic too.”

For his take, Yazdanian is presenting a radically different idea: an improvised duet between piano and the kamancheh, an Iranian string instrument. The music will be played live at each showing of the film, informed by the images on display.

“Just as the film itself is an adventure, we use the music as an adventure and an instinctual response to the images,” he says. “Alongside my collaborator Adib Rostami on kamancheh, we use written guidelines for the sequences but otherwise play what we feel in the moment. That way, we can go along with the audience’s feelings. It’s important to follow this emotion and also to allow space for silence and not overwhelm the images and storytelling on screen.”

As important as leaving that room for silence and improvisation is Yazdanian’s choice of instrumentation and arrangement.

“I wanted to finally use real Iranian colour and instrumentation with our own modes and melodies of playing,” he says. “It feels like the obvious choice for a film with this setting following these people, while the addition of the piano creates a dialogue between the instruments and is also a nod to classical silent film scores that would often be partly improvised piano scores.”

In particularly dramatic moments, such as the tribe’s use of inflated goat skins to create rafts that can withstand the rapids of the Karun river, Yazdanian is also planning to use sticks to create harsh percussive sounds on the piano, while Rostami will play on an Iranian hand drum called a tombak. “It’s a blend of east and west,” he says. “Much like the journey of these western film-makers, following the tribes to the remotest parts of Iran to make this documentary.”

Cultural critic and film historian Babak Elahi sees Yazdanian’s new score not only as a rebuttal of previous versions’ western perspective but also as a reframing of the film’s own colonialist viewpoint. “In the intertitles early on in the film, the film-makers express how they are going in search of the ‘Forgotten People’,” he says. “The documentary has this orientalist viewpoint of white film-makers coming to gawk at tribespeople and their strange customs. While their footage shows such a richness of cultural representation, moving from Turkey to Kurdish, Arab and Persian spaces, their text and framing makes them simply ‘other’.”

Elahi argues that the right scoring can help create a new narrative. “Music intercedes between the word and image of silent films, therefore if you have an orientalist soundtrack it will only reinforce these film-makers’ framing,” he says.

“There is a 1992 score for Grass that was created by the Iranian composer Amir Vahab that tries to recreate a sense of cultural geography, drawing on Persian music, Arab maqam, Turkish folk and Kurdish traditional music to create a different, complex cultural setting. Peyman’s score will build on this and take it into new territory. He’s channelling Iranian musical history as well as referencing how western instrumentation like the piano has become increasingly important in modern Iranian music, making the score relevant to today.”

For Yazdanian, the main substance of his score remains to be seen, since it will be created on the night as he watches the film alongside the audience and his collaborator Rostami.

“We’ve tried rehearsing it a few times together but we have been careful to not play too much as if we did, we would kill the idea and lose our spontaneity,” he says. “It’s going to be scary to perform but it’s also like life where you’re never quite sure what might happen next. Whatever you think of the film-makers’ politics or intentions, it is still so important for audiences to witness the existence and persistence of this tribe that is now largely unknown. This is our Iranian story and we must continue to tell it in new, creative ways.”

Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life is screening with live music from Peyman Yazdanian at Kings Place on 19 September.

Newsletter

Newsletter