I chose to not be a mother so I could be free

I am working on a family tree that is richer and more expansive than tracing the original patriarch

When one of my nephews was a toddler, his babysitter asked him where his Tante Mona lived.

“At the airport,” he replied, without skipping a beat.

He would often accompany his dad, my brother, to pick me up and drop me off at the airport when I visited them. It wasn’t quite a malapropism, but you could make the argument that I spent more time at the airport than in my actual home in New York because I travelled so frequently.

This is one of the reasons why I chose to be childfree.

When one of my nieces was eight, she told me she had been looking up pictures of our family online.

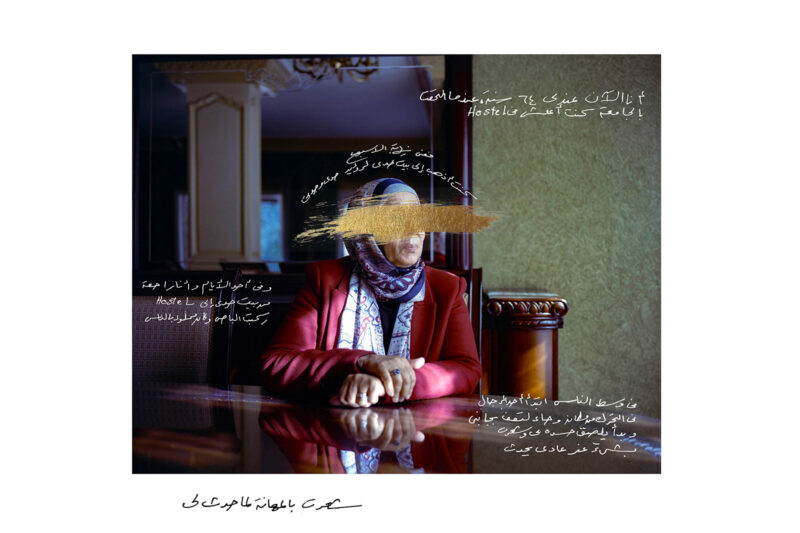

“I saw one of you…” she paused. It was a photograph of my arrest in New York after I spray-painted over a racist, pro-Israel advertisement in the subway in 2012. I thought she had come across the picture of me with my arms in casts after Egyptian riot police assaulted and then arrested me in Cairo the year before. I then showed her that image, and she asked me why the police had broken my arms. “They wanted to make me go home and stop protesting.”

I told her it didn’t deter me. “Good,” she replied, and we went on to spend the afternoon together, talking about the importance of protest.

I chose to be childfree so I could be arrested twice in as many years.

I chose to not be a mother so that I could spend five weeks helping my sister and her husband with their firstborn, in awe and admiration at their evolution into loving parents. I could hold my sister’s baby to my chest and feel the euphoria of pure love and return home still happy that I did not have kids of my own.

I can enjoy that unconditional love without the resentment I know I would have felt over the life change that a child would have required. I am a joyful aunt, but I would’ve been a miserable mother.

But really, I should have never been childfree, because my extended family is so fecund and full of progeny.

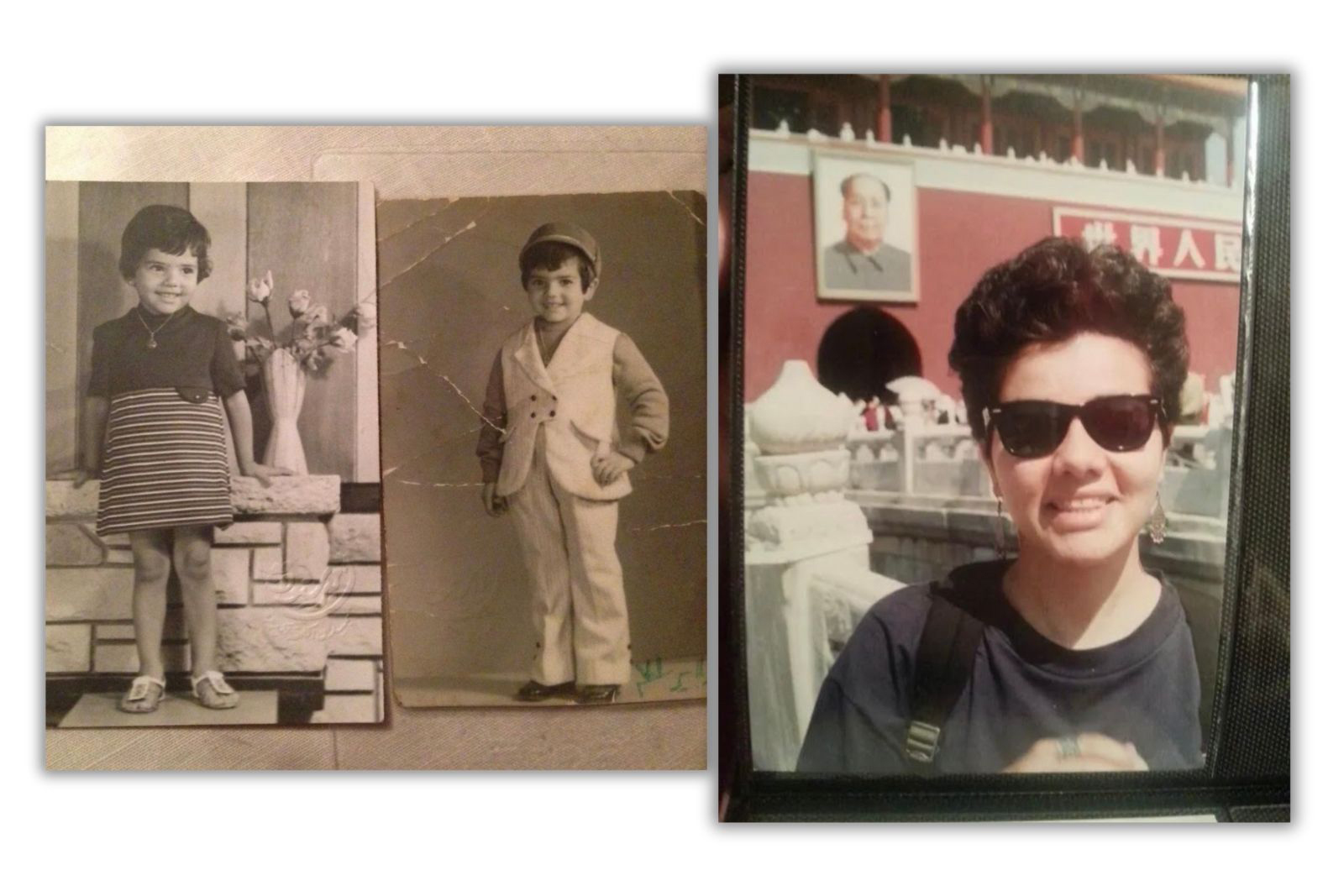

I am the oldest grandchild on both sides of my Egyptian family. I was born into a family that excelled at baby making. My paternal grandmother had eight children. My maternal grandmother had 11 (she was pregnant 14 times). My mother was the eldest and she has three children of her own.

When I was growing up — as is mostly still the case — Egyptian women were expected to wait until they got married to have sex, and to get pregnant as soon as they married.

The only examples of childfree women I knew were two aunts, and it was not by choice for either of them.

But when I was 16, I vowed that I would never allow myself to be in a situation that I could not walk away from. The previous year my family had moved to Saudi Arabia, where I felt suffocated and stifled. The shock at the way my life and that of my mother were curtailed was so sharp that I often describe that time as a form of trauma that found a relief and channel in feminism.

Without actually saying “I’m never going to have children” — and without thinking about children at all — I had made a decision there and then to never become a mother.

By the time I was 35, I was divorced and had kept that promise to myself. My mum asked me: “Are you happy like this?” And I said I was. She and my father had never pressured me. Just as they waited patiently for my brother and his wife, and my sister and her husband, to bring grandchildren into their lives several years into their respective marriages.

At 58, I am still happy with the life I have created. I have never wondered what it would have been like to have children. I have never regretted it. I was lucky that I had the freedom to choose and I wonder what that freedom would look like for all.

I know — from my social circle of Muslim women and women from the Middle East — that more are having children outside what has traditionally been “acceptable”, or not having children at all. Single women, queer women, people who are co-parenting with a friend. But such arrangements are still so taboo that in 2017 an Egyptian TV presenter was sentenced to three years in jail for daring to talk on her show about ways to become pregnant outside of conventional marriage.

When I started speaking about this subject in public, women would track me down in a corridor, backstage, or in the bathroom, to whisper: “Thank you. I have never heard another woman say that out loud before.” In order to break this stigma and to feel less alone in our choices — whether being childfree or creating alternative families — we need to hear from more women, trans and non-binary people of colour, and from different cultural and faith backgrounds.

My family name Eltahawy can be traced back 12 generations. It is somewhat of a family badge of honour to be able to recite them all. But the names all belong to men. I am more interested in my foremothers. I am Mona, daughter of Ragaa, daughter of Na’ima, daughter of Amina. I often wonder what my ancestors would think of me and my family tree. I am working on one that is richer and more expansive than tracing the original patriarch.

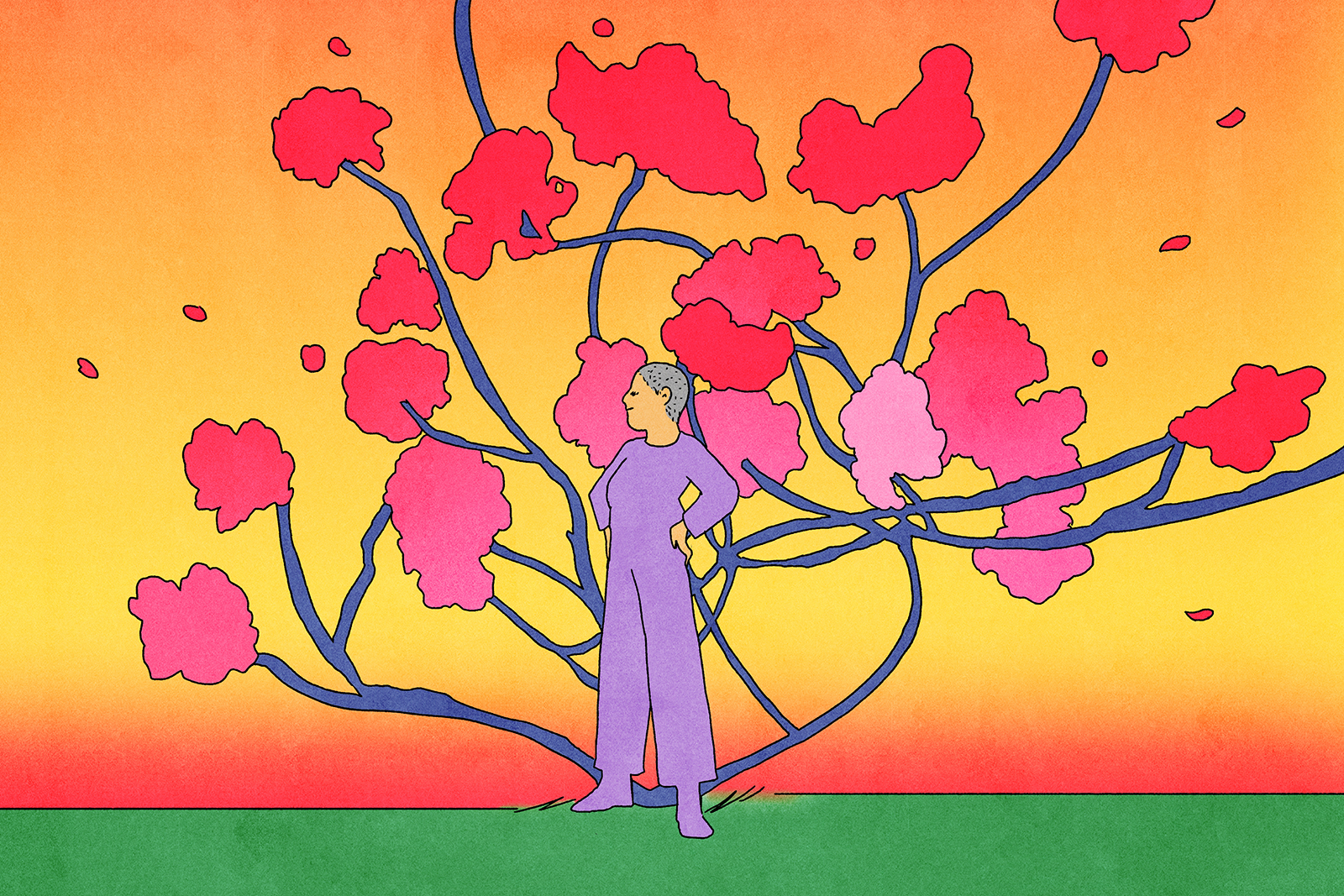

There is more than one way to grow, to see the branch that ends abruptly with me, as not “less” as in childless, but as “more” — blossoming with love, rebellion and freedom.

I know that if I’d had a daughter, I would have taught her to disobey everything I taught her. If I had a daughter, I would have insisted that she be free.

Newsletter

Newsletter