‘The everyman’s saint’: why St George’s story doesn’t belong to the far right

From Ethiopia to Palestine, the figure has been embraced as a symbol of faith and resilience by people around the globe

Adam Kelwick, the imam of Liverpool’s Abdullah Quilliam Mosque, was in Mecca when hand-painted St George’s crosses began appearing on the city’s mini-roundabouts in August.

Kelwick logged on to his social media accounts. “St George was Turkish,” he posted. “Just saying.”

The light-hearted comment didn’t go down well. Kelwick was accused of “typical Muslim BS” and “anti-British disinformation”.

“I just wanted to provoke people a little bit to think about the person who the flag is named after,” he says. “Were St George to come to this country today, he would probably find that the flag didn’t represent him or might even symbolise hostility towards him.”

In recent weeks British and English flags have been popping up in towns and cities across the country in what some believe to be an expression of patriotism, but which others see as part of a wider anti-immigration movement — especially as protests continue against people seeking asylum.

Though Prime Minister Keir Starmer has voiced support of flying the St George’s cross, Operation Raise the Colours, the campaign behind the flags, has received a donation from the far-right group Britain First. Some local councils have also been scrambling to remove them over safety concerns.

“In principle, there shouldn’t be any issue with somebody wanting to demonstrate symbols of loyalty and patriotism, but that’s not what I’m interested in,” Kelwick says. “The flag of St George is being abused and becoming a symbol of intolerance, especially towards immigrants or people of different ethnic backgrounds.”

Since the 18th century, St George has been remoulded as the quintessential Englishman — with Coventry and Tintagel even claimed as his birthplace. But St George’s origins are more commonly believed to stretch back to ancient Palestine. He is an enduring cultural symbol throughout the regions of the eastern Mediterranean, south-west Asia and Africa. The soldier, who was sentenced to death by Roman Emperor Diocletian in the fourth century for refusing to renounce his faith, is claimed as a national hero by countries as far flung as Palestine, Malta, Ethiopia and Georgia.

“Obviously St George was around many, many years ago and there are a lot of different accounts of his life,” says Kelwick. “But he was a great man who is revered in the Islamic tradition as well.”

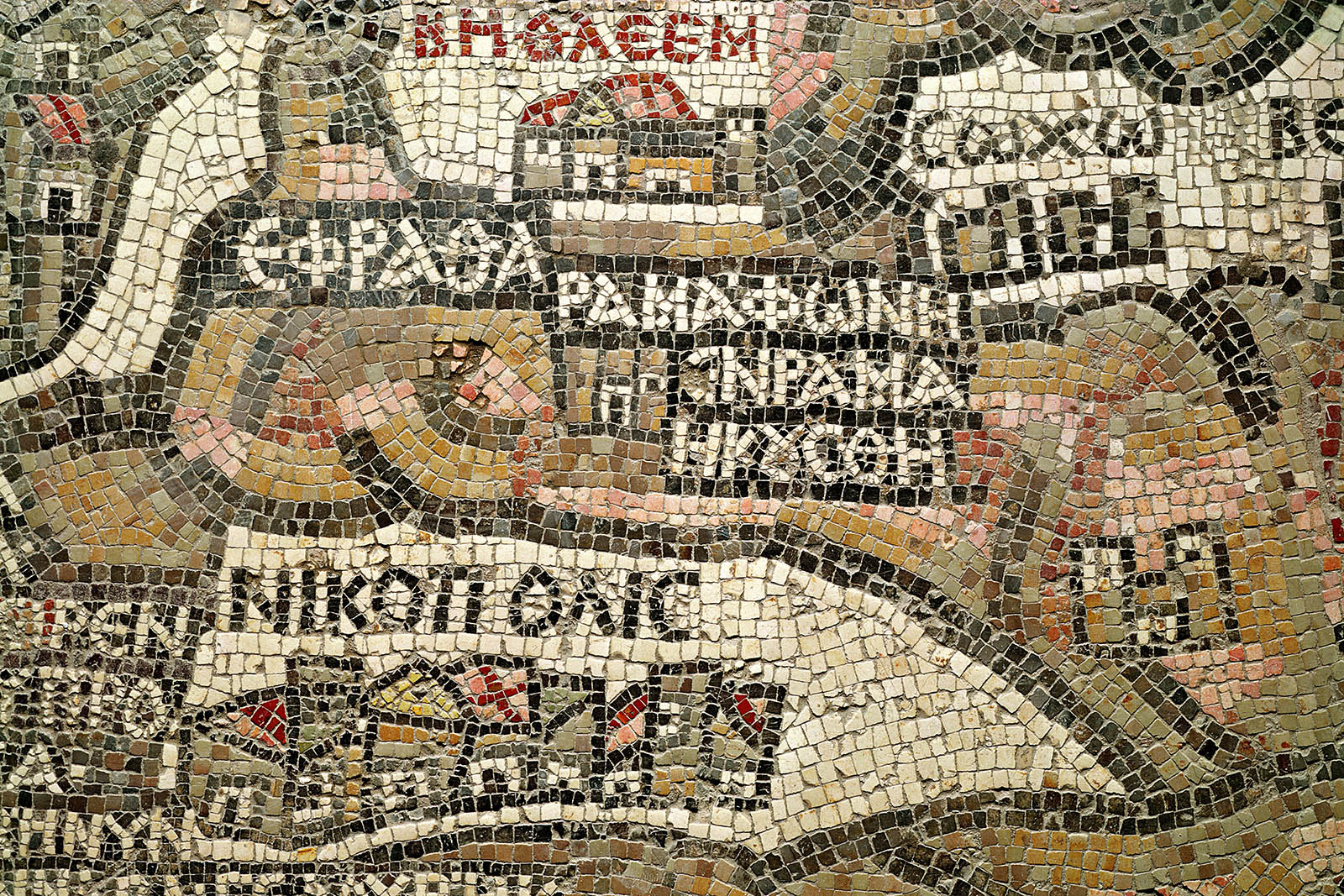

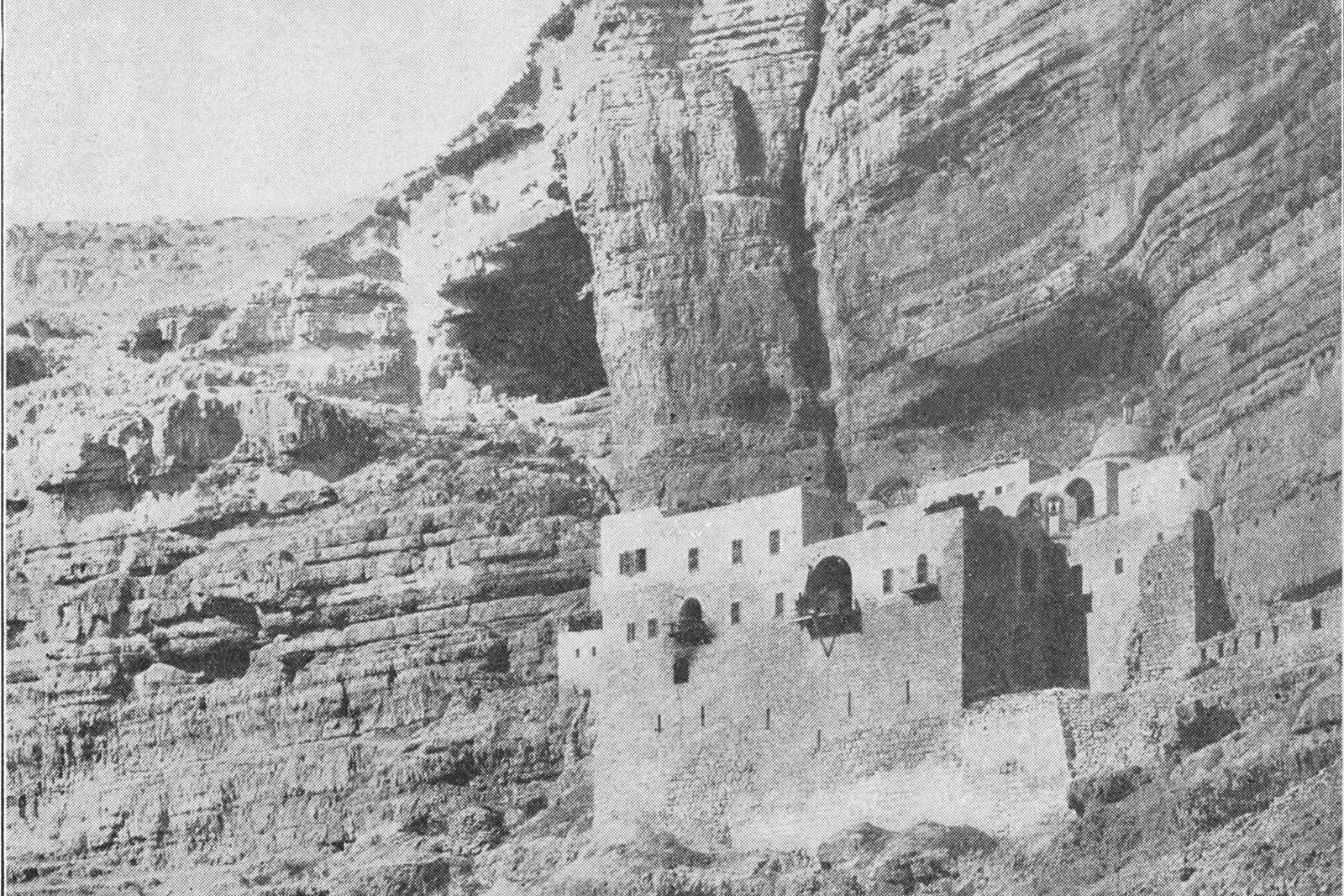

A Greek Orthodox shrine in the West Bank town of Al-Khader, close to Bethlehem, claims to mark the place of St George’s martyrdom. It is a cultural space treasured by both the local Muslim and Christian communities who celebrate the feast of St George.

“Both Muslim and Christian families come together. They bring their children, they bring food, and they line up outside the church,” says George Tsourous, a social anthropologist at the University of Newcastle who conducted field research in Al-Khader between 2014 and 2016.

“What is really striking is how neighbours and friends stand side by side, asking the saint for healing or for protection. For the local people, they don’t understand that this is an interfaith event, it’s just a shared act of devotion.”

For Christians in Al-Khader, St George was a local man who lived and died in the town. He has become a symbol of national resilience for many Palestinian Christians, according to Tsourous.

Most West Bank Muslims interviewed by Tsouros identified St George as al-Khidr, a figure in Islamic traditions associated with wisdom, healing and the sea.

“There are two interpretations of St George in Islamic writings,” adds Kelwick. “One names him as Jirjis, which is how he is often referred to in Palestine, and the other school of thought holds him to be al-Khidr, or the Green Man, but both see him as a man of God — a positive force.”

One of the earliest written accounts of the saint’s life, dating to about the fifth century, survives in the Greek tradition. It describes St George as being born in Cappadocia, modern-day Turkey, to Greek Christian parents. According to the account, following his father’s death, St George returned with his mother to her home town, Lydda — modern-day Lod in Israel. There he joined the Roman army and was subsequently tortured and killed.

“There is very little historical evidence of a real person who did any of the things which are associated with St George,” says Sam Riches, a cultural historian based in Lancaster, who has researched the medieval cult of St George for more than 30 years. She suggests that the figure who eventually made it into the historical record might be an amalgamation of several people, as is true of many early Christian martyrs.

“You often come across people making very definitive statements about his birthplace and there are many arguments of people trying to put a modern label of nationality on him,” she says. “But on a personal level, I find the concept of St George being Palestinian a lot more persuasive than him being from Cappadocia. There is a very strongly rooted and powerful tradition of St George there.”

England is not unique in its attempt to localise St George within its own borders. He is said to have broken up a siege in Malta, slayed a dragon in Baden, and rescued slaves on the shores of Crete, to name just a few of the places that claim a physical connection. But Riches says the history of the saint’s cult in England is unique in its monarchical origins.

While in Palestine, Lebanon or Ethiopia, St George has for centuries been the “everyman’s saint”, willing to help everyone with their daily problems and struggles, in England his veneration had been primarily the prerogative of the aristocracy throughout the medieval and Renaissance periods.

According to Riches, in the 18th and 19th centuries St George was recast as an Englishman and began to be gradually used as a symbol of empire. It was through this route that he has been absorbed into far-right iconography.

“If they knew anything about St George’s cult, they wouldn’t be nearly as keen on him as they think they are,” she says. “But I think we are lucky to have St George and be in this family of nations who share an interest in him.”

Meanwhile, Kelwick, who is still in Mecca, says he is considering flying his own St George’s cross when he gets back to Liverpool.

“I want to claim the flag back, let them know it’s ours,” he says. “What’s most important is that we stop being racist, Islamophobic and fascist. Whether the figure of St George is reclaimed from the right, well, that’s secondary.”

Newsletter

Newsletter