What you need to know about plans to disclose suspects’ ethnicity and nationality

New guidance for police could see more details made public about people who have been charged with a crime. Here’s what it could mean for Muslims

Police forces are being encouraged to disclose the ethnicity and nationality of suspects when they are charged in high-profile and sensitive cases. Experts warn that the move could put Muslims at risk while deepening mistrust between communities and the police.

The guidance was introduced earlier this month by the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) and the College of Policing, and has been presented as a step towards greater transparency.

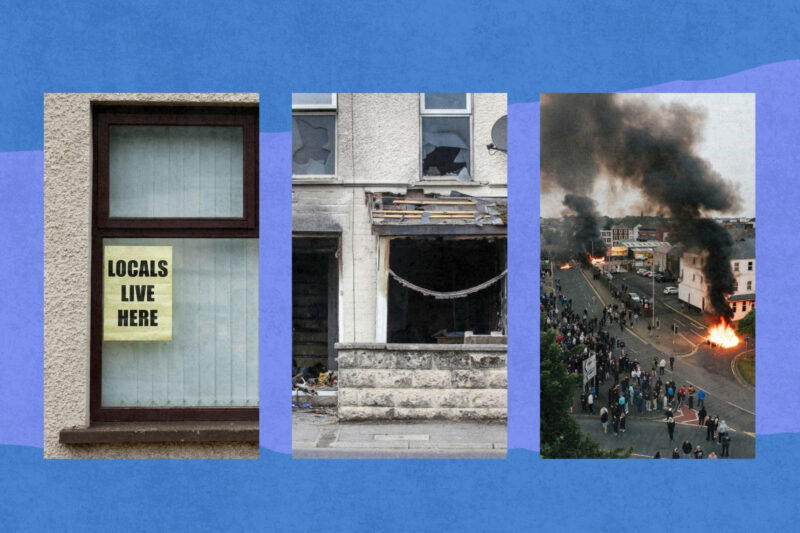

It comes just over a year after far-right riots broke out across the country, triggered by false online claims that the killer of three girls in Southport was a recently arrived Muslim immigrant.

The family of one of the girls killed in the attack has already criticised the new guidance, saying ethnicity is “completely irrelevant”. But the NPCC and the College of Policing claim it will counter misinformation and disinformation, and build confidence in policing.

Currently, no law prevents police from releasing information about a suspect’s nationality, ethnicity or immigration status once they’ve been charged with a crime. The decision to disclose these details remains at the discretion of each force. It’s just that, with some exceptions, it’s not routinely done.

Why are police moving to release information about suspects’ nationality and immigration status now?

“It’s a reactive policy,” said Tahir Abbas, professor of criminology and global justice at Aston University, linking the new guidance to the 2024 riots, when “misinformation led to so much violence and destruction, creating tragic outcomes”.

Abbas noted a later incident in Liverpool in May, when a car drove into people during a football victory parade. Within two hours, Merseyside police announced that the suspect was white and British.

“If there was no information, people would jump to negative conclusions,” he said. “Everything from Muslim terrorists to immigrants who arrived on a boat.”

The guidance says decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis by the most senior investigating officer in consultation with the force’s communications chief, and could be applied where speculation poses risks to public safety, or where high levels of misinformation exist.

Shabna Begum, chief executive at the Runnymede Trust — a race equality thinktank — warned that the guidance risked reinforcing the idea that certain groups were inherently criminal, fuelling suspicion.

“Disclosing ethnicity or immigration status is always going to create a sense that this information is somehow significant,” she said.

In early August, following the arrest of two men in connection with the alleged rape of a 12-year-old girl in Warwickshire, Reform UK leader Nigel Farage demanded that police publish their immigration status. Home secretary Yvette Cooper also said she wanted to see “more transparency in cases”.

“The framing of this guidance as ‘transparency’ does align with demands from sections of the public who want crime to be narrated through an ethnic or immigration lens,” said Nasar Meer, professor of social and political sciences at the University of Glasgow.

What could the changes mean for anti-Muslim hate?

A 2025 Runnymede Trust report analysed words from news articles and parliamentary debates on immigration over four years and found that migrants were most often associated with the word “illegal”, and subjected to racist stereotypes, including portrayals of Muslim migrant men as threats to women.

This narrative has fuelled demonstrations outside hotels housing people seeking asylum. In Epping, Essex, protests erupted after a resident was arrested on sexual assault charges. The high court later banned the Bell hotel from accommodating people waiting for refugee status.

The guidance has been presented as a way to head off rumours that can fuel unrest — like in Liverpool. But in other cases where a suspect is from a minority background, Begum warned that tropes, including Muslims being “cultural outsiders” and “Muslim men in particular being sexually deviant”, could be “encouraged”.

Meer agreed: “This is primarily about reassurance rather than accountability. The reassurance is targeted at majority populations and at audiences already receptive to far-right framings of crime. It is not designed to reassure Muslim or migrant communities, who in fact are placed at greater risk.”

In February 2025, Tell Mama — an organisation that had recorded incidents of hate against Muslims, which has since been replaced by the British Muslim Trust — found that there had been a 165% increase in anti-Muslim hatred and Islamophobia in 2024 compared with the previous year.

“If ethnicity and immigration status are publicised, far-right activists can use that information to mobilise hostility against mosques, community centres, or individuals who are visibly Muslim,” said Meer, explaining that “anti-Muslim violence spikes after political rhetoric about migration or crime”.

Mosques around the country, including in Sunderland and Southport, have beefed up security, installing new CCTV systems and new doors. “Everyone is much more vigilant around their own personal safety,” said Begum.

Women are particularly at risk from Islamophobia

Abbas also warned that Islamophobia is gendered. “Muslim women, in particular visibly Muslim women, continue to face the brunt of Islamophobia because of their visibility,” he said. Yet protesters who gather outside hotels often condemn gendered violence and claim that they want to protect women and girls.

Police data released to the Guardian under freedom of information laws found that two out of every five people arrested after participating in the 2024 riots had been previously reported for domestic abuse.

Begum said she agreed with the more than 100 women’s rights groups that wrote to prime minister Keir Starmer and Cooper in August to warn that violence against women and girls had been “hijacked by an anti-migrant agenda”. “Misogyny is a real problem, but it is not a racialised problem,” she said.

Are suspects’ ethnicities publicised in other countries?

Similar moves in Germany and Denmark have been criticised for fuelling far-right narratives.

Meer said the international parallels were “troubling”, noting that in France police routinely highlight Muslim identities of suspects, while refugee status being linked to crime after 2015 “generated panic and emboldened far-right mobilisation”.

“The outcomes show a clear pattern: when ethnicity or religion is made a headline issue in policing, it increases hostility against minorities without improving safety,” he said.

Newsletter

Newsletter