What Westminster is saying about Reform’s first attempt at migration policy

Nigel Farage has given the public a glimpse of what a Reform UK government might do — including deporting 600,000 people

Nigel Farage has never been shy about saying what he thinks. But one of the main criticisms of him and his Reform UK party over the past year has been their lack of detail on small boats and asylum seekers — namely, what exactly they would do if they were ever to enter government.

That changed this week when Farage unveiled what he called a comprehensive plan to reduce migration to the UK, involving deporting up to 600,000 asylum seekers in a single parliament. But beyond the headlines, what sounds bold at first glance quickly becomes complex.

The centrepiece of Reform’s plan is the pledge to deport asylum seekers who arrive in the UK on small boats. Delivering this would require Britain to withdraw from the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) — the treaty safeguarding fundamental freedoms across 47 Council of Europe countries, including the UK.

The ECHR protects the right to life and bans torture and inhuman or degrading treatment. Under it, the UK has a legal duty to assess asylum claims to ensure no one is sent back into danger. Withdrawal would strip away those responsibilities.

Critics also warn it could undermine the Good Friday Agreement, as implementation of the ECHR in Northern Ireland is promised in the text and embedded within the hard-won peace deal. Farage says he would renegotiate the deal but, given that reaching the original agreement took 700 painstaking days, that promise sounds fraught with risk.

Nor would leaving the ECHR be straightforward. Reform can’t enact any of this unless it wins a parliamentary election. Even with a majority, its legislation would need to pass through both the Commons and Lords, and would almost certainly provoke fierce resistance.

After that, the UK would still need to notify the Council of Europe and give six months’ notice. And if the aim is to remove all legal barriers to deportation, the UK would also have to withdraw from the UN Convention Against Torture, which prohibits returning people to countries where they face persecution. Untangling these obligations would be a legal and diplomatic marathon. Any suggestion it could happen overnight is, at best, unrealistic.

So what about those who arrive in the meantime? Reform’s answer is to expand Britain’s detention system — vastly. At present, there are just over 2,500 places in so-called processing facilities. Farage said on Tuesday that he wants to raise that to 24,000. Even with funding, the practical hurdles to that are immense. Constructing new facilities or finding suitable empty properties could take some time.

Then there is the question of where asylum seekers would actually be sent. Reform says it would strike new return deals with a range of countries. But we saw the Conservatives’ Rwanda plan mired in court battles and lengthy negotiations. Farage’s plan to strike bilateral deals involves him setting aside £2bn of public money to fund them.

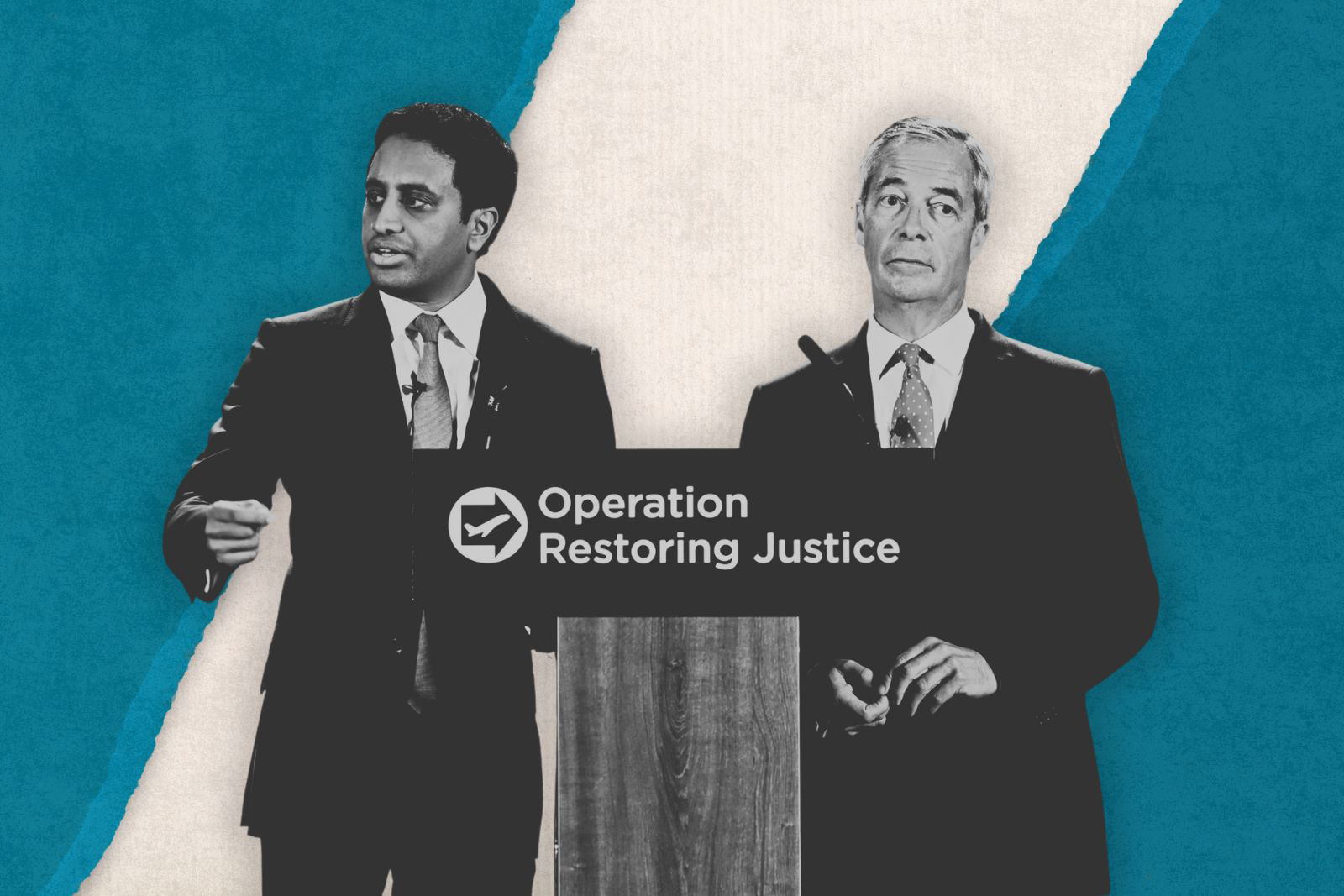

Zia Yusuf, Reform’s head spokesperson for the party’s proposed department of government efficiency — a title inspired by Elon Musk’s initial role within Donald Trump’s administration — even suggested countries such as Afghanistan and Eritrea might be interested in a financial agreement. But that would involve negotiating with regimes such as the Taliban — a prospect that would be diplomatically controversial, to say the least.

Reactions to the plan have been mixed. One Labour MP told me they were pleased Reform was finally being explicit about its positions: “Once they start actually sharing policy details, they will face scrutiny and people will see their policies are unworkable.”

Another, however, admitted concern. “Farage has come up with policies which, although they can’t work in reality, sound good to people, and many may want to vote for it,” they said.

These plans, either way, are still very much in their infancy. Journalists were given a four-page policy document outlining them. The party has said there is a 100-page plan that has not been released yet. The exact costings, and how everything will work, are therefore impossible to scrutinise.

The Conservatives were publicly unimpressed. “Nigel Farage is simply reheating and recycling plans the Conservatives have already announced,” said Chris Philp, the shadow home secretary. That may be true, but Farage has a knack for cutting through to the public in a way no current Conservative seems able to.

The Liberal Democrats took a different approach. Before Brexit, the UK had a returns agreement with European neighbours that vanished when Britain left the EU. Small boat crossings have surged since then. Lib Dem leader Ed Davey says that, far from stopping small boat crossings, Farage — by campaigning for Brexit — has caused them to increase. Reform, however, insists that is unfair, noting Farage played no role in the post-referendum Brexit deal.

Ultimately, with just four MPs, Reform is still far from power. But the party is riding high in the polls, and pollsters I have spoken to believe British politics is undergoing a major realignment that means nothing is impossible.

That is why Reform’s policies demand close scrutiny. Farage says he is preparing for government. This, then, is one of his first serious attempts to show what that might look like.

Shehab Khan is an award-winning presenter and political correspondent for ITV News.

Newsletter

Newsletter