Epping Forest asylum hotel victory is a timebomb for Labour

Labour pledged to stop using hotels to house those seeking asylum by 2029. Its timetable has shrunk — but some MPs say the smart thing to do is keep waiting

The row over the government’s use of hotels to house people awaiting asylum decisions has reached a new and volatile stage, feeding into the national debate about immigration, public safety and Labour’s ability to deliver on its promises.

The high court on Tuesday sided with Epping Forest district council, granting the local authority an interim injunction against the use of a local hotel to house people seeking asylum. The decision — made on the basis of a planning dispute — has implications beyond the town of Epping. It has potentially emboldened other councils to go down the same path, unsettled ministers, and highlighted how fragile the politics of asylum have become.

The judge in the case, which will be listed for a full hearing later this year, also concluded that the Bell hotel in Epping had become a public safety risk owing to the protests that were taking place outside the property. For the Home Office, this has created an immediate headache: it now has less than a month to find a roof for the approximately 140 people currently housed there. Legally, at least, it cannot leave them destitute.

It is a row that escalated in July, when a man seeking asylum who was staying at the hotel was charged with sexually assaulting a 14-year-old girl. Another resident now faces multiple assault charges. The allegations, which both men deny, prompted thousands of protesters to gather outside the hotel. Supporters of people seeking asylum turned up, too, and the confrontations occasionally spilled into violence. Essex police say 16 people have been charged with offences relating to the disturbances.

Such events rarely remain local for long and the controversy has already reverberated far beyond Essex. First the Conservatives, when they were in government, and now Labour have pledged to reduce the use of hotels to house people seeking asylum. The practice has been widely viewed by politicians as both costly and a symbol of the small boat crossings that both parties have made a central issue. Equally, a number of charities have spoken out about poor conditions within those hotels.

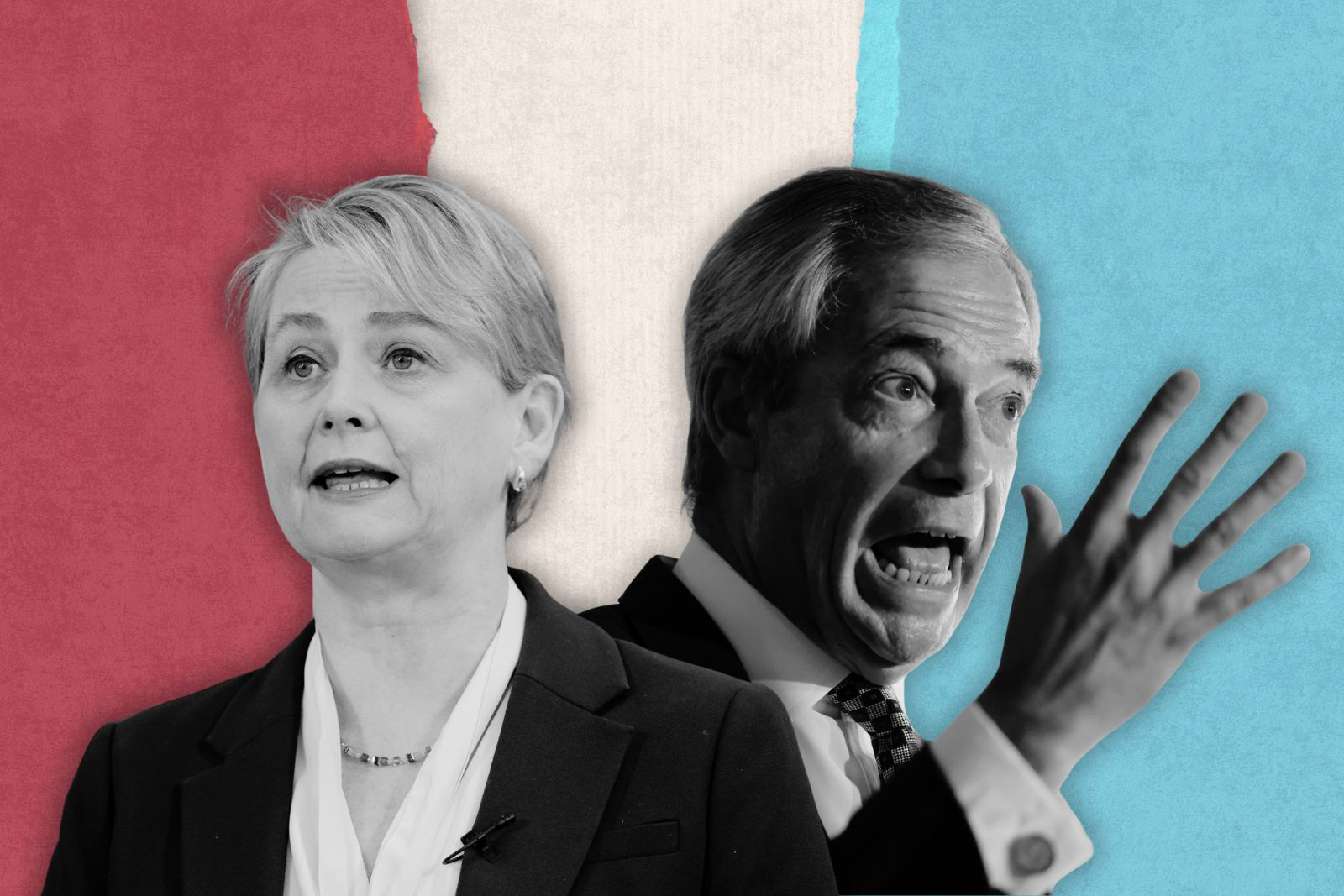

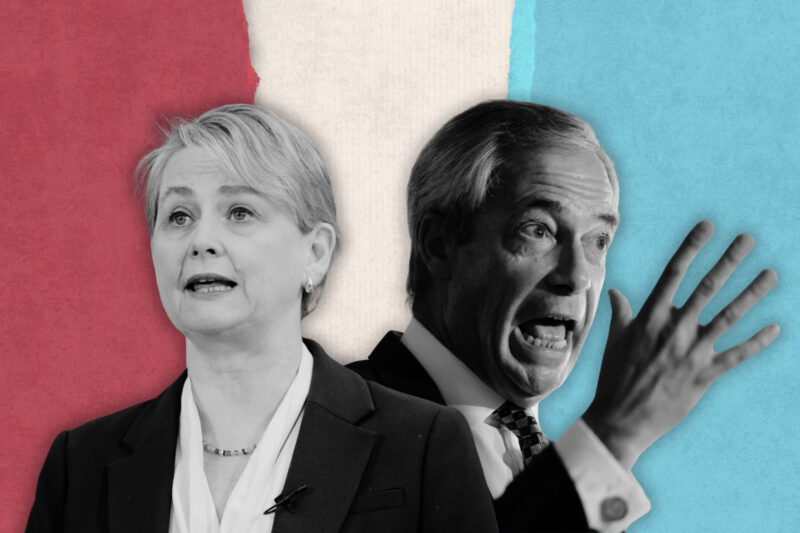

Now this latest judgment has left councils around the country deciding whether they should follow suit and mount similar challenges under planning rules. Reform UK’s leader, Nigel Farage, has promised that all 12 councils under his party’s control will “do everything in their power to follow Epping [Forest]’s lead”.

Labour ministers have long been desperate to reduce reliance on hotels, insisting it was a system they inherited and was only ever intended as a short-term solution. In 2023, more than 400 hotels were in use at a cost of £8.3m a day. The figure has since fallen to 210 hotels, costing £5.77m daily.

The target, outlined in the Labour party election manifesto, remains to reach zero hotel usage by the end of the current parliament in 2029 — but this ruling could force the government to act much faster.

There are 32,000 people seeking asylum who are still housed in hotels and precious little in the way of options for where to accommodate them. Social housing is already woefully stretched. Should they be left to live in tents, as Reform’s new Greater Lincolnshire mayor Andrea Jenkyns suggests? Such camps would not exactly be well received by the public and could breach the Home Office’s legal requirement to provide accommodation for people whose claims it is assessing. They would also, of course, raise ethical questions over the UK’s treatment of those seeking refuge. Should the government build new asylum accommodation in remote areas? That would be costly and couldn’t happen overnight. It could also lead to similar protests wherever the accommodation ended up being built. There are no immediate answers.

Across Westminster, there is concern that taxpayers’ money will be drained in court battles, while the political risk of more protests grows if people feel empowered by the Epping Forest precedent. Ministers are preparing an appeal against the high court decision but there is no guarantee it will be successful.

As one Labour MP put it to me, the issue of asylum and immigration is eating up time across multiple departments: the Home Office managing asylum claims, the justice system dealing with potential cases, diplomats negotiating agreements with other countries to get boat crossings down. But several backbenchers have told me that they believe the best course of action would be to wait for the government’s appeal and take it from there — they say there is no clear silver bullet solution.

Immigration and asylum are now consistently ranked by YouGov as the most important issue to voters — outranking the economy, health, education and even housing since the start of the summer. Labour won an overwhelming parliamentary majority at the last election, but electorally its foundations are shallower than they look. Labour secured just 34% of the vote, the lowest share for a governing party since the first world war, yet translated it into 411 seats. That’s the equivalent of 42 seats per million ballots cast — the most efficient conversion of votes into seats in modern history.

There are 89 Labour seats where Reform came second. Fail to “get a grip” on immigration, as Labour MPs who are concerned about losing their seats put it, and many of those could be in play. But Labour also faces pressure from the Greens and independents and potentially the new party launched by Jeremy Corbyn. If votes continue to leak leftwards as well as rightwards, the consequences for Labour could be dire.

What makes this moment unusual is that the old rules of politics seem not to apply. In the past, when a government lost popularity, the opposition automatically gained it. That has not been happening with the Conservatives: as they sink, it is Reform UK that has been surging. Immigration is central to that. In other words, the more volatile this debate becomes, the more fragmented British politics looks.

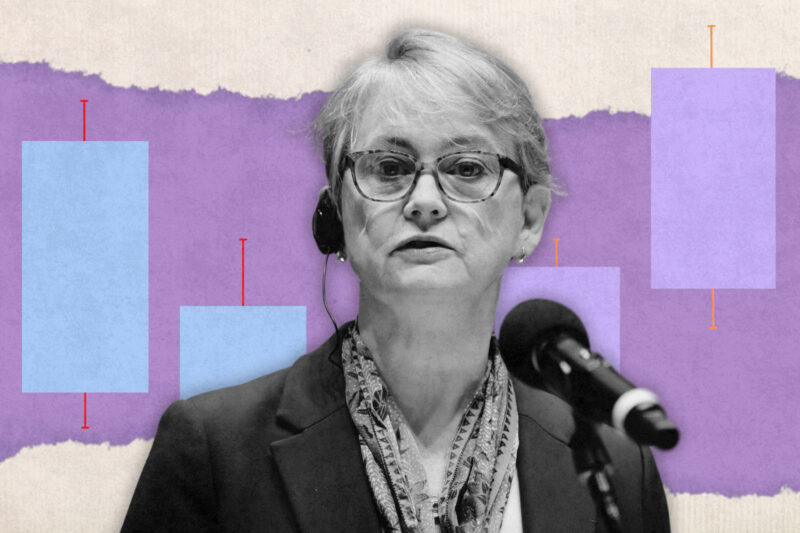

Shehab Khan is an award-winning presenter and political correspondent for ITV News.

Newsletter

Newsletter