Meet the Gen Zs retelling the history of Partition

Hobbyist historians are using TikTok to explore the events of 1947 and beyond

Growing up in Virginia, Rida Ali, 25, had a vague understanding of the events surrounding Partition. She knew her family moved from Gujarat, India to Karachi, Pakistan when the Indian subcontinent gained independence from the British in 1947. But when she started to study South Asian history in university, she was shocked to learn that it was the largest forced migration ever recorded.

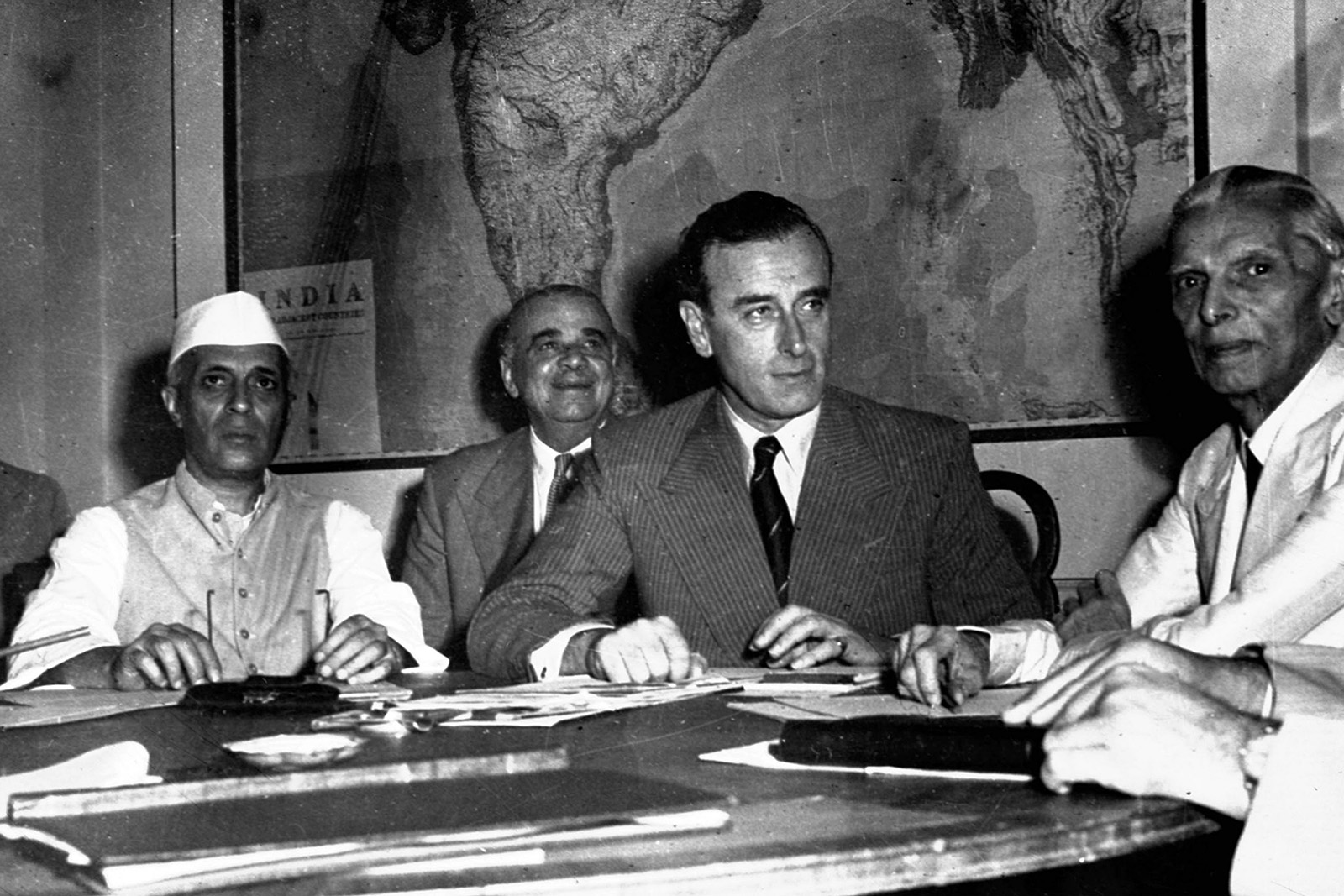

She was also flabbergasted to discover that it was the British who determined the borders of the new nations. “You’re telling me that we didn’t even get to choose what the boundaries looked like?” Ali, who is now based in New York, recalls thinking.

So when she launched a TikTok channel five years ago focused on South Asian history and culture, Ali dedicated early videos to primers about Partition, such as explaining how British lawyer and civil servant Cyril Radcliffe, who famously hadn’t been east of Paris, was tasked with determining the new borders of India and Pakistan in five weeks.

Radcliffe’s decisions unleashed severe consequences for around 390 million people living in India, West Pakistan and East Pakistan, which is now Bangladesh. Around 15 million people were forced to migrate, with violence leaving an estimated one to two million dead. While the borders aimed to address the religious fault lines between majority Hindu and Muslim populations, minorities such as Sikhs, Christians and Buddhists were largely ignored.

Ali is part of a wave of Gen Z historians — both formally-trained and hobbyists — making this history accessible by sharing their research on TikTok and Instagram. Accounts like Ali’s and Brown History on Instagram are not only educating their audiences where school curriculums have failed them, they are providing South Asians in the diaspora a fresh lens through which to see their own histories.

For 18-year-old Sarin Kishna, learning about Partition has become a way of making sense of politics today — in particular, a resurgent Hindu nationalism both in India and among his diaspora friends in the Netherlands. Kishna, whose mother is from India and father is from Suriname, has been particularly disturbed by the hate he sees towards Muslims.

“Everyone’s either turning to a dangerous ideology, or just wanting to learn more, like me,” Kishna said about his peer group, speaking from his home in Almere.

He’s been doing deep dives on social media, following accounts like Uncivilized Media, a US-based YouTube channel that aims to promote underrepresented voices in retelling history. This led to Kishna opening up new conversations about Partition with his family. Kishna recently visited Canada to see his grandfather, who grew up in what is Bangladesh today, living through the events of 1947 and raising his family in Kolkata.

“He’s been through so much,” said Kishna. “He’s been displaced so many times.”

Kishna is also learning about how Partition fuelled inter-communal unrest, such as the Bengali language protests in 1952 that erupted in response to Urdu being the sole official language across East and West Pakistan. “I never even heard about the language protests and how much pride the Bengali people took in their language, and even died for it,” said Kishna, who described his history education at school as “very Eurocentric”.

Highlighting personal histories

Even within existing Partition narratives, the history of the division of Bengal between India and modern day Bangladesh is often less prominent than the bifurcation of Punjab. “Sometimes I feel like a minority within a minority,” said Iftishamul Nihal, a Bangaldeshi-American content creator based in West Palm Beach, Florida.

The 23-year-old decided to create his own Instagram channel, naming it Bideshi, meaning foreigner in Bengali. Nihal uses archival photos and video to revisit events, including the attempted invasion of Bengal by Japan in the second world war, the Bengal famine of 1943 and the lead up to Bangladeshi independence in 1971.

“It took off really fast, which told me that people shared that sentiment I had,” he said. Nihal’s accounts, bideshi.co on TikTok and @the.bideshi on Instagram, now reach upwards of 46,000 followers.

Nihal isn’t a historian by training but his father sparked his interest in Bangladesh by having books around the house and peppering family history into conversations, like mentioning that his father had campaigned for the Muslim League, a dominant political party during the pro-independence movement against the British. “If you are a nosy person, history is the right thing for you. And I’ve always been nosy in that way — curious about stories,” said Nihal, who relies on academic and primary sources wherever possible.

He thought it especially important to highlight the 1971 genocide in Bangladesh at the hands of the Pakistani military. Nihal said he had learned about the Holocaust in great detail at school, but there was no mention of the 1971 genocide in his history books. “It’s not about whose suffering has been worse,” he said. “For me, it is important to make sure the world knows that this happened.”

These social media primers are also bolstered by better-funded initiatives explaining the legacy Partition to Gen Z audiences. Scottish historian Sam Dalrymple, who grew up primarily in Delhi, recalls a night in 2018 with friends from Pakistan and India who were lamenting that they could not cross the border to visit their ancestral homes due to visa prohibitions. “It’s almost like these places no longer exist to you anymore — like they’ve been lost,” the 28-year-old told Hyphen.

That conversation sparked the idea to create Project Dastaan, which employs virtual reality to connect people who migrated during Partition with the homes that they left behind. It was founded in 2018 by Dalrymple and Saadia Gardezi, now a PhD candidate at the University of Warwick, and Sparsh Ahuja, an Indian filmmaker now based in Australia.

The project initially took off on Instagram,with people sending their family’s accounts of Partition for consideration. “The aim was to take as many people back as we could, using virtual reality to transport people back across the border who hadn’t been back in 75 years,” said Dalrymple. “Unfortunately, I was the only one who could really cross over with ease — the irony, of course, is that it’s easier for Brits to travel across these South Asian borders than it is for South Asians themselves.”

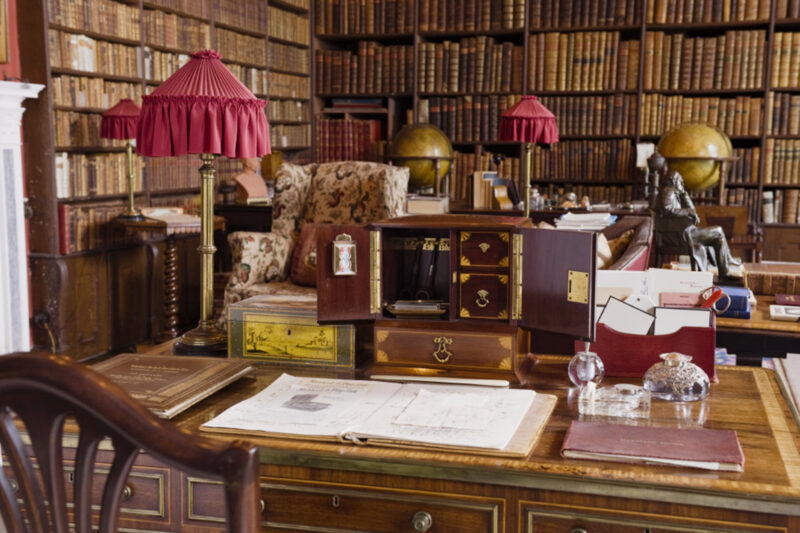

The Covid-19 pandemic brought this work to a halt, redirecting Dalrymple and his co-founders to create animations that fed into an exhibition about Partition that is now travelling around the world. The pandemic also led Dalrymple, who is the son of historian William Dalrymple, to write a book reexamining the withdrawal of the British, arguing there were many partitions in post-empire India, the most recent being the creation of Bangladesh. In June Dalrymple published Shattered Lands: The Five Partitions and the Making of Modern Asia, which has become a number one bestseller in India.

The book is bringing his work with Project Dastaan to a broader audience. On one stop on Dalrymple’s book tour, a young Rohingya man approached him and told him he was inspired to do something similar for his own community. “He was going to get in touch with some Burmese friends who still could go back to try and film and show the landscapes that everyone’s remembering in the diaspora that they can’t visit,” said Dalrymple. “So that’s been a lovely response.”

For Nihal, some of the most satisfying feedback he has received has come from those in the Indian subcontinent. “A lot of the people that are learning things for the first time are from Bangladesh or West Bengal,” he said. “That’s both surprising and really encouraging. It’s a good sign we are covering topics that need to be covered.”

Newsletter

Newsletter