The Berlin space opening its doors to Palestinian voices

Protected by the wealthy German entrepreneur who funds it, the Spore Initiative is defying state efforts to silence pro-Palestinian voices in culture with a series of exhibitions and events

It’s a warm summer evening and 50 people are squeezed into the concrete foyer of the Berlin space Spore Initiative. The audience, students in keffiyehs sitting beside grey-haired pensioners, are listening intently to a panel of journalists and academics discussing the history of Israel and Palestine.

“Hundreds of thousands of people are chanting ‘Palestine will be free’, but it’s important to talk about what that actually means,” panel moderator, journalist and former Middle East correspondent Kristin Helberg tells the room in German. “Is it two separate states? Or one state in which everyone has the same rights? And what does that mean for people living in Israel, and for Jewish people worldwide?”

It’s not a controversial conversation, but the Spore Initiative is one of the few places in Germany where it can currently take place. All discussions around Palestine have been taboo in German public discourse since the 7 October Hamas atrocities and Israel’s subsequent military retaliation.

“I call it the shelter,” said Haig Ghokassian, who helped arrange the evening’s panel event. “[For people] looking for a space where they can feel safe and talk openly.”

Located in Berlin’s Neukölln neighbourhood — the heart of the city’s Arab community — the Spore Initiative opened its doors in April 2023, just six months before 7 October. It was founded by German entrepreneur, venture capitalist and philanthropist Hans Schoepflin together with Mexican-Cuban artist and curator Osvaldo Sanchez.

“The Spore Initiative was imagined as a space dedicated to ecosocial justice, where culture is understood as a tool for change,” Shoepflin told Hyphen. He describes his initial vision of artists and curators working with communities around the world, using art to help communities on the frontlines of climate change. “We wanted to move away from typical, top-down institutional approaches, and instead let people and communities speak for themselves.”

Born into an entrepreneurial family whose fortune was made from a mail-order company, Schoepflin built on this legacy with a successful career as an investor and was an early shareholder in the company that became Costco. He started to question the unchecked power of large corporations after the 1999 WTO protests in Seattle and describes being “radicalised” when teargassed at an anti-globalisation demonstration in Canada in 2001: “I experienced for the first time what it’s like to have a view that does not line up with the current government and the mass media.”

Later that same year, Schoepflin and two of his siblings started the Schoepflin Foundation with a mission to support free speech and democratic values. Schoepflin provides this foundation with €12m annually, from which it funds projects including investigative journalism outlet Correctiv and provides grants for local media organisations. Standing up to power, he says, “is not possible without a free press”.

As Israel’s destruction and siege of Gaza intensified, human rights experts including Amnesty International expressed concern that Germany’s firm support of Israel was tipping over into attacks on free expression and assembly. In June, the Council of Europe’s human rights commissioner Michael O’Flaherty wrote to Germany’s interior minister outlining his concerns over restrictions on freedom of expression.

The institution’s founding director Antonia Alampi was disturbed by “a sudden escalation” in oppression and a hardening of discourse, both on the nearby streets and in the wider cultural sphere. There have been multiple reports of police violence at pro-Palestine demonstrations in Neukölln.

Alampi recalls her shock when the Berlin Senate announced on 6 November 2023 that it would be reviewing its funding of the Oyoun cultural centre after it hosted an event for the local activist group Jewish Voice for a Just Peace in the Middle East. Berlin’s Constitutional Court found that its later decision to cut funding had no legal basis, but the threat sent a chill through the city’s cultural community. “The fact that no public figures or institutions said anything about [what happened to Oyoun] was very scary for me,” Alampi said.

Just three days later, on 9 November, the Spore team issued a statement offering their support to Berlin communities who felt silenced or discriminated against — naming in particular anyone facing anti-Arab, anti-Muslim or anti-Semitic discrimination — and opened its doors to them. The decision wasn’t an easy one. Alampi was concerned that the venue’s stance could endanger its staff, visitors and supporters.

Berlin’s Office for the Protection of the Constitution has labelled the boycott, divestment and sanctions movement BDS “anti constitutional”, potentially giving police and security services greater powers to target those speaking in favour of it. Alampi consulted lawyers for advice on their rights if, for example, police arrive in riot gear and try to stop an event. “It was stressful. For a time, I was speaking to lawyers more than anyone else,” she said.

As the institution is not reliant on external or state funding, the Spore Initiative was less vulnerable to financial injury but, as Alampi points out, there are other ways of being attacked. In Oyoun’s case, local media ran a series of articles accusing the venue of hosting antisemitic statements — claims that a Berlin regional court later ruled were false.

Alampi had the full support of the Schoepflin family. Their foundation had never previously funded projects directly related to Israel and Palestine, but Hans Schoepflin recognised that free speech was under threat. In order to create change, he explained, “you have to make space for people to talk about their realities.”

When Ghokassian, a senior figure in German tech, Israeli orchestra conductor Ido Arad and journalist Kristin Helberg started discussing panel events around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict — which became Zeit Zu Reden (Time to Talk) — they took the idea straight to Spore. “We felt there was nowhere else at that time where these discussions were happening,” said Ghokassian.

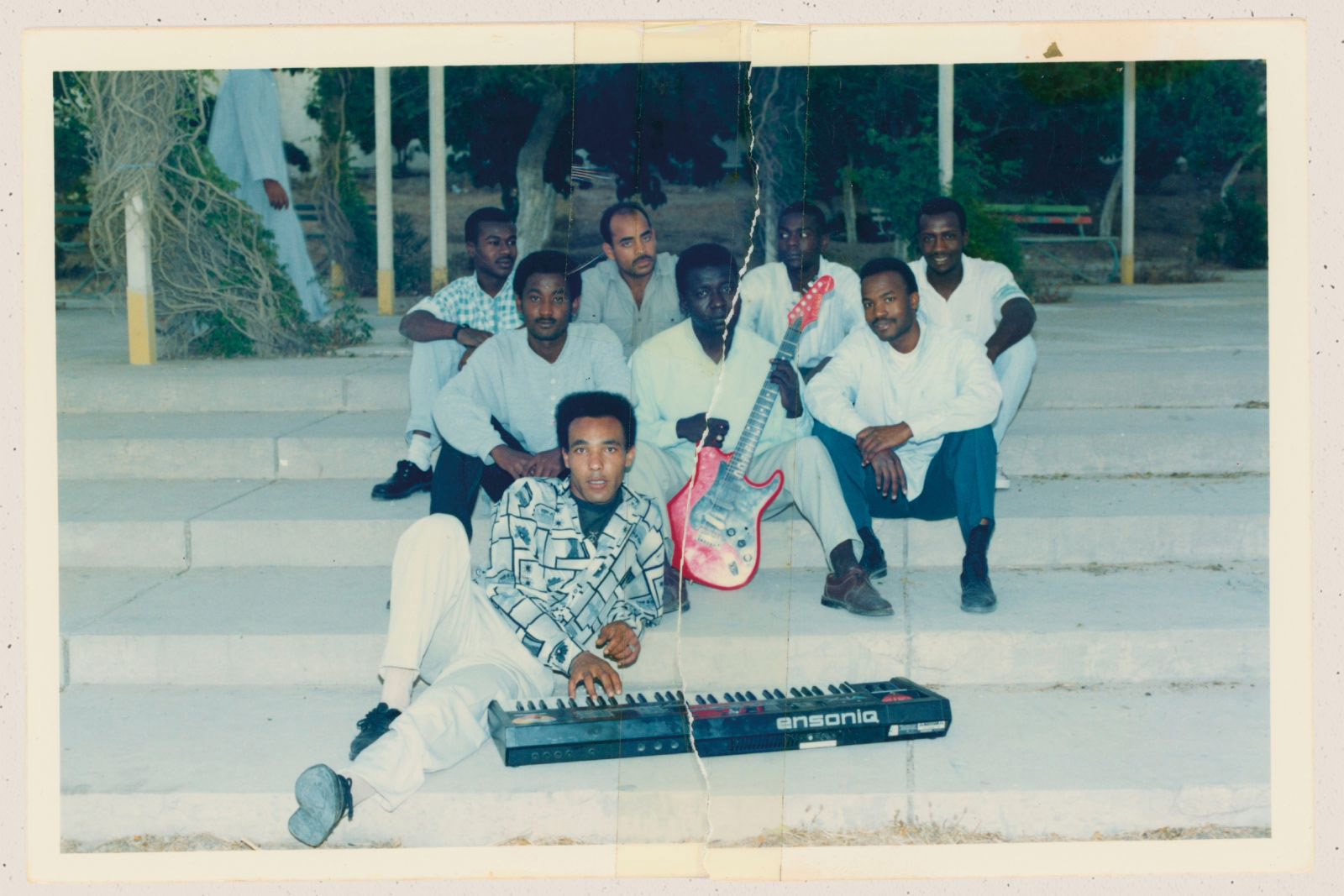

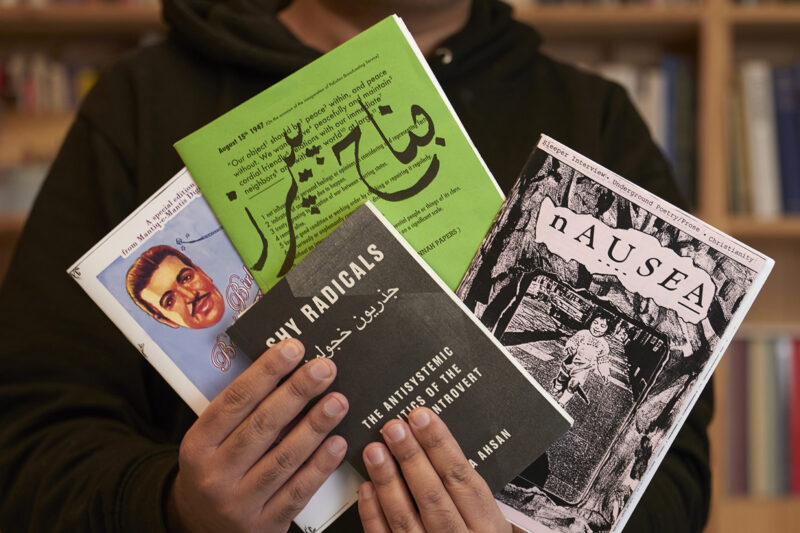

The space is currently showing a group exhibition, ‘aʿmāl al-‘arḍ — Landworks, Collective Action and Sound, developed alongside Dar Jacir, an art space and farming cooperative in the West Bank. Earlier this month, it hosted a two-day symposium on the Palestinian economy. It has also worked with Haitian, Filipino and Kurdish minority diaspora groups. “There are many communities here who do not feel heard,” Alampi said.

Although shocked by the state oppression of pro-Palestinian voices, Alampi says it has created opportunities to challenge entrenched structural discrimination that has too often been overlooked. “There’s always been a set of people who decide what gets funded and what doesn’t, but the reasoning isn’t always explicit,” she said. “Now some of the reasoning behind these decisions has become crystal clear. And when you make them visible, you can in turn contest them.”

This article was amended on Monday 4 August 2025, to remove references to the Spore Initiative being a gallery. The article also incorrectly stated that the Spore Initiative is the Schoepflin Foundation’s latest project and that it was founded by Hans Schoepflin and two of his brothers, rather than siblings.

Newsletter

Newsletter