Telegram under fire again as ‘living room’ for far-right extremists

Analysts say online agitators who fuelled anti-immigrant riots in Spain are part of an international network exploiting the platform’s relaxed content moderation

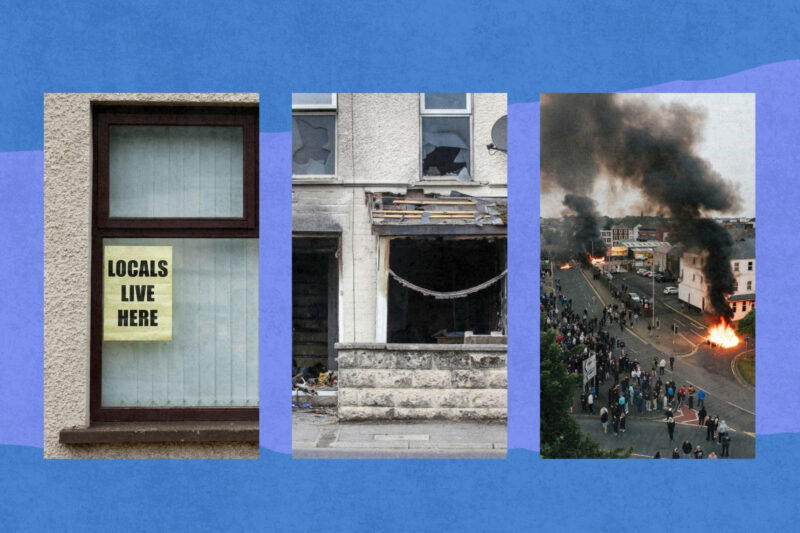

The arrest and detention of an alleged far-right ringleader in southern Spain following three nights of anti-immigrant violence has once again put the spotlight on social network Telegram, with disinformation experts accusing the platform of failing to adequately moderate posts.

Telegram this week denied claims that it had allowed Deport Them Now — a Europe-wide network of far-right militants calling for the mass deportation of immigrants from western countries — to disseminate hate unchecked, culminating in the violence in Murcia that resulted in 14 arrests. It is the latest scandal involving the platform’s alleged use as a space for the extreme right to organise.

“Calls to violence are explicitly forbidden by Telegram’s terms of service and are removed whenever discovered,” it said in a written statement. “Moderators proactively monitor public parts of the platform and accept requests in order to delete millions of pieces of harmful content each day, including calls to violence.”

Spanish journalists and web analysts, however, argue that extremist groups, including Deport Them Now, prefer to use Telegram precisely because of its comparatively lax moderation and a history of pushing back against calls from authorities to shut down problematic channels.

Marcelino Madrigal, a Spanish web analyst who monitored social-media activity during and after the recent riots believes the Deport Them Now Telegram channel served as a “living room” for people to talk and organise. “It provided the infrastructure for groups to chat in,” Madrigal said.

According to the court order for his arrest, issued on 17 July and reviewed by Hyphen, the far-right ringleader — identified only by his initials CLF — used Telegram channels to call for residents of Torre Pacheco to “hunt” down all north Africans in retribution for an assault on an elderly resident. He is accused of inciting hate, forming an illicit association and illegally bearing arms.

On 9 July, a 68-year-old man was physically attacked by three men during an early-morning walk through the small town and left with a black eye. As news circulated that his attackers were of north African descent, messages appeared on Deport Them Now’s Telegram channels asking supporters to form patrols and chase down the perpetrators: “enact direct justice and reunite them with Allah”

Fake images of the beating and of the alleged perpetrators also circulated on social media, including a video of a white man on the ground, pictures of his bruised face, and mugshot-style pictures of darker-skinned men. None of these images had anything to do with the 9 July assault. The man being beaten up in this video later came forward to identify himself, saying that his aggression had taken place in a different town and that his attackers had been white, according to local media. The correction made little difference.

For three consecutive nights, rioters wielding batons and chains roamed the streets of Torre Pacheco, terrorising immigrants and vandalising kebab shops. According to the court order, the group’s intention “was to create a violent and racist climate with the goal of enacting violent behaviour towards people of Moroccan origin residing in Torre Pacheco”.

This violence was mirrored online. A report by the Spanish Observatory on Racism and Xenophobia, part of the Ministry for Inclusion and Migration, found that the amount of hate speech on social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and TikTok was between 2,000 and 5,000 messages a day until 11 July when the number rose to almost 7,000. On 12 July, it spiked to more than 33,000, according to the report, which doesn’t include messages on Telegram.

Darren Loucaides, a journalist who has covered Telegram extensively, told Hyphen: “When things like [the Torre Pacheco beating] happen, they’ve already got an infrastructure set up to take advantage of. The far right is fairly at home on Telegram.”

Telegram generally complies with authorities’ requests to shut down a channel, which can happen when it publishes hate speech or calls for violence, but the company’s policy on shutting channels down has been criticised as opaque. According to Loucaides, Telegram is more likely to take down content if it perceives a risk of being removed from Apple or Google Play. Nor does the closure of a channel necessarily stop a group using Telegram. The Spanish Interior Ministry ordered the closure of one Deport Them Now channel following the riots only for a new one to pop up immediately.

Unless Telegram receives reports about every Deport Them Now group and makes a conscious decision to track them all going forward, Loucaides said: “It just won’t get picked up. It’s just not that systematic.”

In May, in the northern Italian town of Gallarate, Deport Them Now and other groups organised a meeting called the Remigration Summit where about 400 far-right activists from various European countries gathered to discuss what they claim is the destruction of Europe at the hands of non-European immigrants and the subsequent need to expel them.

The concept of remigration — or mass deportation — is rooted in the concept that a “white genocide” is taking place in the west. In Europe, the idea of forced remigration gained momentum among the far right after the 2011 publication of the book The Great Replacement by French author Renaud Camus. The widely-debunked ideology, which suggests that white people are being “replaced” by non-whites, initially had an Islamophobic spin but has shifted to encompass a more general anti-immigrant sentiment. Shortly before the Torre Pacheco riots, Spain’s far-right party Vox, which has 33 members in the nation’s Parliament, called for the expulsion of millions of immigrants from the country.

Despite CLF’s arrest, Madrigal believes the lack of attention paid by authorities and media across Europe to extremist groups online is dangerous. He admits, however, that the threat of the far right extends beyond social media: “If someone in parliament calls for the expulsion of millions of immigrants, the problem isn’t only on the internet, is it?”

Newsletter

Newsletter