How ‘emotionology’ fuels the far right

One year after the worst racially motivated riots in decades, the extreme right continues to employ fear, anger and even nostalgia to stoke resentment against Muslims and immigrants

The riots of July and August 2024 were a terrifying reminder of a longer trend demonstrating how the anxieties of white communities in Britain can target some of the most marginalised communities in our society. As a historian who studies the extreme right and how emotions work in history, I suggest there is an emotional context to the 2024 riots. The violence directed at communities in Southport, Liverpool and elsewhere were not an isolated outpouring of emotive aggression, but part of a longer pattern of extreme hostility towards non-white communities.

Fears of white communities being replaced by immigrants have often driven unrest in the UK. In the wake of the first world war, migrant communities living primarily in port towns were targeted, often quite violently, by returning white soldiers who were convinced the new arrivals would usurp their jobs. In 1958, both Nottingham and Notting Hill saw riots by white “teddy boys” confronting recently settled Black Caribbean communities, with tensions exploited by extreme right groups such as the White Defence League and Oswald Mosley’s Union Movement.

By the 1970s, groups such as the National Front marched in the streets of the UK, and attacked non-white communities, leading to a number of killings, such as the textile worker Atlab Ali, stabbed in Whitechapel in 1978. In the summer of 2001, rioting broke out in Oldham, Burnley and Bradford, stoked by groups such as the British National party, as well as alarmist reporting in the local press.

Both historically and today, the extreme right promotes an emotive narrative of a UK under attack, where white people face an existential threat from “aliens”, “foreigners”, and “immigrants”, be they Jewish, Black, Muslim, those seeking asylum or another hated “other” allowed to enter the country by corrupt politicians. While some factual details are included in extreme right literature to rationalise this narrative, it is one pushed on social media by the evocation of emotions such as fear, anger and a hatred of immigrants, as well as love, pride and nostalgia.

What some historians describe as an “emotionology” — a set of instructions on how to think and feel — came to define the riots of 2024. Emotions are a sort of social glue that holds together otherwise quite diverse people. The emotionology that 2024’s rioters connect with was triggered by the tragic killings on 29 July in Southport. But it has also been fostered by mainstream politicians who worry about race and integration in ways that accentuate otherness, and a tabloid media that is suspicious of groups such as Muslim communities and regularly labels Britain as a “soft touch” on immigration.

The summer 2024 riots provided an emotive event that allowed the extreme right’s framing to take hold. In the immediate aftermath of the murderous attack in Southport, online misinformation about the origins and motives of the attacker was spread by both extreme right networks and a range of “mainstream” voices that ought to have been more responsible.

These conspiracy theories saw a vigil in Southport on 30 July disrupted by violent anger and attacks on the police as well as a local mosque. Images of the rioting were widely shared on social media and helped spread violence across England and Northern Ireland for the next week. As in previous riots, extreme right agendas materialised as anger, fear, resentment and hatred became manifest on the streets.

The emotionology underpinning the riots was framed initially in doubt and suspicion about the Southport attacker. These were sentiments sown by people who talked ambiguously of the “truth” being withheld from the public. Nigel Farage epitomised a wider emotive framing when he asked on social media “whether the truth is being withheld from us” by the authorities. What is interesting here is not the deployment of facts and details, but rather how emotions were stoked by simply “raising questions”, feeding uncertainty and disbelief.

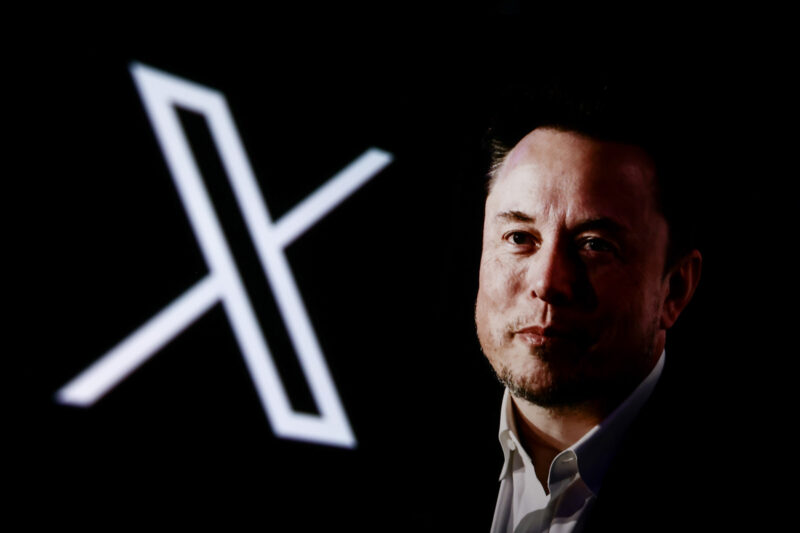

Meanwhile, the social networks including X, Facebook and Telegram, that stoked much of the rioting, were steeped in overt expressions of emotion. Think of the paranoia stirred up by extreme right and neo-Nazi groups who saw the riots as opportunities to make themselves relevant, or the supporters of Tommy Robinson that linked his imprisonment to the context of the emerging unrest. There was also the failure of X to remove emotive material while its owner, Elon Musk, suggested that “civil war is inevitable”. Such misinformation amplified emotional responses for thousands of those who engaged in rioting and provided licence to take action.

The violence also saw rioters express their emotions in the devastation they left behind. The targets were consistent: mosques as symbols of the Muslim community they feared, immigration hotels as symbols of migrants they hated and the police and their vehicles as emblematic of the state they distrusted. The attacks on such targets followed a highly emotive agenda and drew on sustained resentments and hostility. These resentments have not gone away.

To understand the riots, it is important to consider the roots of this resentment. This anger has been generated over many decades and is far more widespread than Britain’s relatively disorganised extreme right alone. Many rioters were not active members of extreme right groups, nor highly ideological. Yet they shared the extreme right’s emotionology, its feelings of distrust of politicians, its fear of others and its misguided idea that violence against such targets can protect a nation under threat. These are feelings that can all too easily be activated again.

A year on, I wonder if the emotive reasons for the rioting have been fully understood by politicians. Since last summer, the Labour government has repeated efforts to talk tough on issues of immigration. Yet these messages accentuate the sense of a nation under threat by feeding into conspiracy theories surrounding the rhetoric and the reality of immigration. Moreover, if Kier Starmer cannot hear echoes of Enoch Powell when he describes the UK as an “island of strangers”, it is unlikely we will see any meaningful routing of the extreme right’s emotionology.

Newsletter

Newsletter