Mental health project that draws on 1,000 years of Islamic psychology turns 10

The Lantern Initiative helps Muslims across the UK tackle anxiety and low mood using the work of psychology pioneers Abu Zayd al-Balkhi and Avicenna

A Muslim mental health organisation that draws on the work of Islamic psychologists dating back more than 1,000 years to tackle anxiety is marking the end of its own first decade.

The Lantern Initiative, launched in 2015 in Milton Keynes, began as a series of coffee mornings with the goal of combating loneliness, especially among young Muslim mothers. Today it has a small army of volunteers, and runs international retreats, conferences and youth work.

“People were yearning to connect their mental health journey with their faith — to find healing practices rooted in spirituality,” said managing director and co-founder Safura Houghton.

The study retreats, which have so far been run in the UK, Spain and Uzbekistan, are intended to give people with low mood or anxiety “a real, in-depth insight into what support mechanisms and healing practices we have within the faith that we can draw on”, Houghton added.

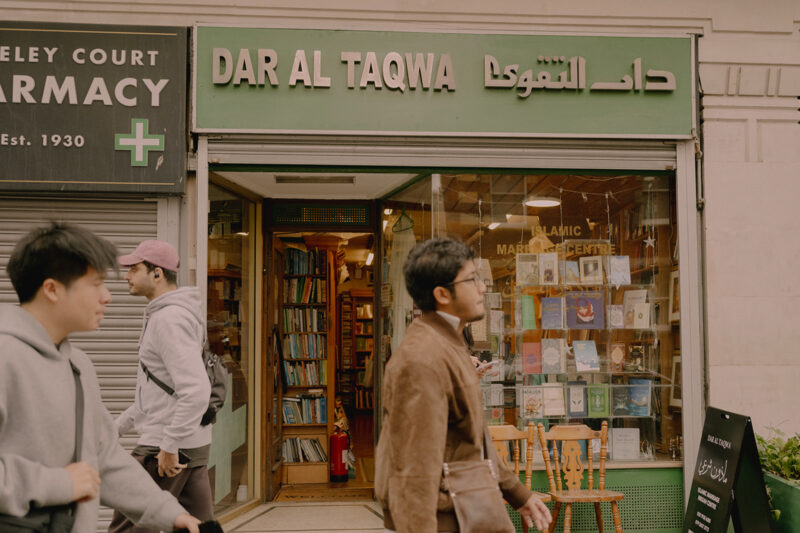

To run them, she and the other speakers and trainers turn to the rich history of Islamic psychology — including the work of Persian psychotherapy pioneer Abu Zayd al-Balkhi, born in 850, and “Prince of Physicians” Abu-Ali al-Husayn ibn Abdalah ibn-Sina, known as Avicenna, born in 980.

“Al-Balkhi was someone who had developed cognitive behavioural techniques and other practices such as talking therapies,” she said. “It’s bringing them back to life, drawing on what already exists from within those faith-based frameworks.”

Donations from local businesses and grants from the local council help cover the cost of free and low-cost events, but competition is fierce. The team now has three volunteer directors and an “ad hoc” group of volunteers — among them former service users, something Houghton is particularly proud of. “It’s really lovely to see people grow from struggling themselves to being in a place where they actually want to help,” she said.

Among Lantern’s programmes is a women-only, half-day event called Healing Minds. Run in six cities so far, and with plans to expand, it sees a panel of female speakers talking about mental health and wellbeing, with the discussions rooted in their faith. It has so far sold out every time.

But the organisation also wants to see mosques and Islamic centres playing a bigger role in tending to the mental health needs of attendees.

“Some of our biggest learnings have come from our landmark report published in 2021, called Muslim Mental Health Matters,” Houghton added. “Our researchers were asking questions and collecting data about the barriers that Muslims face when it comes to mental health support. One of the biggest areas we identified within that research project was the role of mosques and how much more work needs to be done.

“Very few people had been supported by a mosque or Islamic centre when it came to their mental health. There were also challenges with the level of mental health awareness and training among mosque committees and faith leaders.”

Houghton wants to see more investment in training so mosques can signpost people to mental health support and services as well as providing their own qualified counselling. “The vast majority of mosques, I think, still feel possibly not well enough equipped to support someone struggling with mental health challenges,” she said. “So that’s an area for the future that we are looking into.”

Newsletter

Newsletter