‘Food is a way to show who we are’: preserving the Sudanese Kitchen

Omer Al Tijani’s new cookbook is an extensive archive of recipes and culinary culture in Sudan

Omer Al Tijani has spent much of his 40 years in the UK, far from the kitchens of his childhood in Bahri and Khartoum, Sudan. He missed the meals that had once been everywhere around him — aseeda, mullah and kisra weren’t easy to find in restaurants or cookbooks. So, in 2016, he began to write down the recipes he could remember and others that he could learn from family members. At first, he did it for himself, then for family and, eventually, for an audience he didn’t realise his work would bring together.

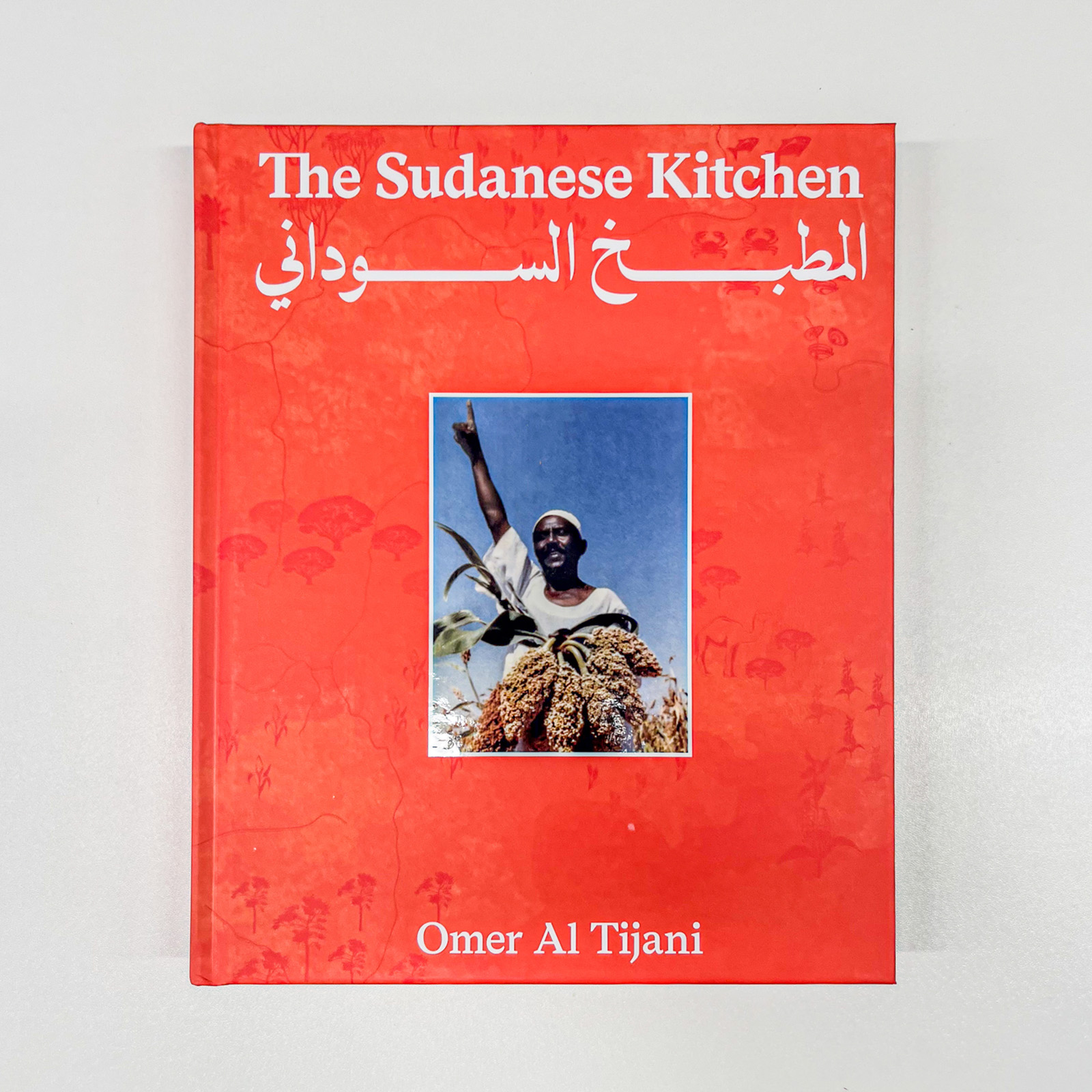

The result is The Sudanese Kitchen, a book featuring more than 100 recipes from across Sudan’s many food traditions. It’s an archive, a reclamation project and, in Al Tijani’s words, “a small act of resistance” against erasure.

“It really just started as a personal archiving project,” he explains. “So that when I wanted to have those dishes, I could look up my own notes, almost like a family cookbook.” The project soon grew to become an online resource for Sudanese recipes, including information about their historical and cultural contexts.

Al Tijani came to the UK in the early 1990s. Back in Sudan he recalls moving fluidly through different kitchen spaces — the men eating outdoors, the women preparing meals for extended family, hired cooks and helpers in the home. He was at the edges, watching, tasting, absorbing.

The kitchen was never a neutral space. Having grown up just a few miles from Al Tijani, in Khartoum, the Sudanese capital, I mention to him how radical it seems that this book is not just written by a man, but has a photograph of one in the centre of its bright orange cover. “The kitchen is very much a women’s domain based on the culture in Sudan,” he agrees. “But I reject that wholeheartedly. I wanted to make food for myself, my people, my community. I didn’t want to rely on female family members.”

In writing The Sudanese Kitchen, Al Tijani disrupts more than one tradition. The book also challenges the wider idea that culinary authority must pass through formal institutions, singular techniques and methods.

It’s a book written by someone inside the culture. He understands its complexity and how the sliminess of your grandmother’s mulukhiya (a jute mallow stew) will always be the best. It’s for those curious about Sudanese culture, and those inside it — especially those who, due to the horrific war that has displaced millions and led to famine, may find themselves far from home. This act of documenting food has become a connection to a home that cannot be returned to.

Sudanese food is often misunderstood, Al Tijani says, either collapsed into Levantine templates or ignored altogether. There is no single “national dish”, no ubiquitous street food export. What Sudan has is a layered, diverse culinary tradition shaped by trade, migration, class, topography and resilience.

“People assume Sudanese food is going to be like Lebanese, Nigerian, Egyptian or Ethiopian food. They don’t realise it’s a fusion,” says Al Tijani. It’s also one that is adaptable to changing diets and access, as more people eat less meat either due personal preference or, as has been the case for much of the Sudanese population, the rising expense of meat over the decades.

The Sudanese Kitchen reflects that hybridity and fluidity. Recipes span fermented sorghum flatbreads, leafy stews, tangy cooked salads and traditional alcoholic drinks that can be traced back to ancient Nubia — in present day western Sudan, the age-old tradition of drinking millet beer, known as marisa, continues, often embraced by devout Muslims who follow Sufi beliefs. The recipes trace regional and ethnic specificity, mapping Sudan’s culinary landscape with precision and care.“These drinks are ancient. They’ve only been demonised recently in the decades after the Islamic revolution,” he says. “As controversial as it may be, they need inclusion and respect.”

That historical consciousness runs through the entire book. Al Tijani spent months researching at Soas University of London and the British Library, drawing on Sudanese oral histories and reaching out to elder relatives, friends and community members. He approached the book as a kind of collective memory, where a single recipe could hold a whole geography and a family history. “It’s about giving language to things people already know in their bodies,” he says.

For readers outside Sudan, sourcing ingredients can be a struggle. Purslane. Dried okra. Baking ammonia. Sorghum flour. Al Tijani knows this well — he’s had to go deep into WhatsApp auntie networks and niche grocer runs to find the right components. Over the course of our conversation, we start trading tips on where to get the cured basturma (beef) or fresh mulukhiya leaves. To an outsider it would seem as if we were discussing procuring goods on the black market. “It does become like that,” he laughs. “Like, ‘Who do you have for this?’ It’s almost like you’re sourcing something illegal.”

He jokes, but the struggle is real. The Sudanese Kitchen responds with a detailed pantry guide and sourcing notes — bridging gaps that many diaspora cookbooks skip over. Al Tijani is also considering launching a digital pantry, offering hard-to-find ingredients shipped directly to readers. That accessibility is central to his vision: not just to preserve, but to enable wider participation and, hopefully, further books.

The book is organised for cooks at all levels of ability, with difficulty ratings and notes on vegetarian options, substitutions and prep times. Al Tijani recommends starting with dishes such as salatat dakwa (peanut salad), mish (a spicy yoghurt dip), or salatat aswad mahrousa (charred aubergine with garlic and lime) as “they’re accessible, but still very Sudanese”.

Some dishes are far more challenging, such as the multi-stage preparation of kisra, a fermented flatbread made from sorghum flour. “Some recipes are like rituals. They bring you home,” he says.

Above all, The Sudanese Kitchen is an act of safekeeping. It’s a record of what can be held onto when borders, wars and languages fail. “Food is a way in. It’s a way to show people this is who we are, this is where we’re from,” Al Tijani says. “This is bigger than me. It’s a cultural artefact.”

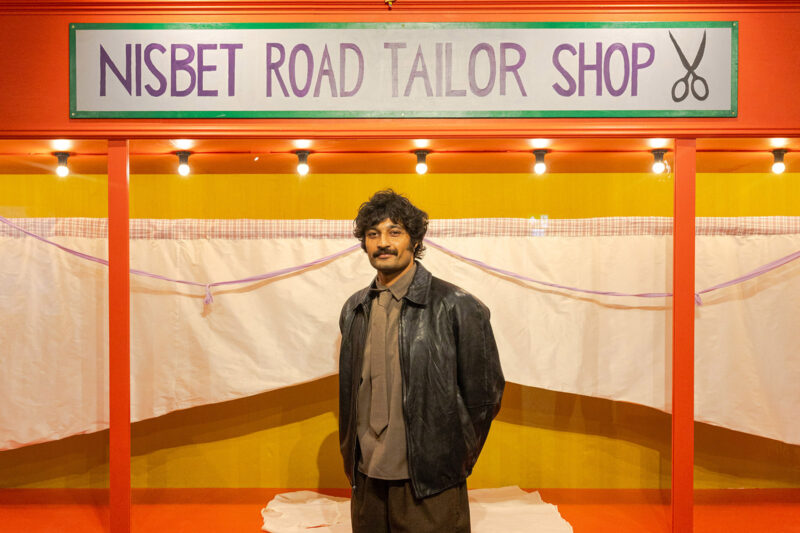

The Sudanese Kitchen is available to buy now and an exhibition of its photographs will run at the Almas Art Foundation in London until 2 October.

Newsletter

Newsletter