Bradford’s madrasas became health hubs — now others are following suit

Pizza bans and stretches before studying the Qur’an are among the ways the city’s Muslim supplementary schools are improving kids’ health

Madrasas in Bradford have become hubs for tackling inactivity and obesity among children thanks to a community-led programme that is now being expanded across the city.

The initiative, known as Join Us: Move. Play (JU:MP), is part of a larger Sport England-funded pilot by the research programme Born in Bradford. JU:MP was introduced across schools, parks and community centres, but its biggest success stories lie in the city’s Muslim supplementary schools, of which there are more than 130 across Bradford.

Research conducted by Born in Bradford found that South Asian girls are among the least physically active demographic groups in the UK, and that 90% of Muslim South Asian children in the city attend a mosque or madrasa daily after school. In Bradford, children of South Asian heritage experience obesity rates at age 11 that are 10% higher than white British children.

“We started looking into how these faith settings can be involved for health promotion without compromising on what they’re already doing and their teaching schedule,” said Dr Sufyan Abid Dogra, principal research fellow at the Bradford Institute for Health Research and Born in Bradford’s lead for communities and implementation research.

At first, the idea of including physical activity and healthy eating into faith settings was met with some hesitation. “There was scepticism about whether public health messaging belonged in madrasas,” said Dr Dogra. “But the data was clear, and we pushed to make sure faith settings were recognised as key delivery partners.”

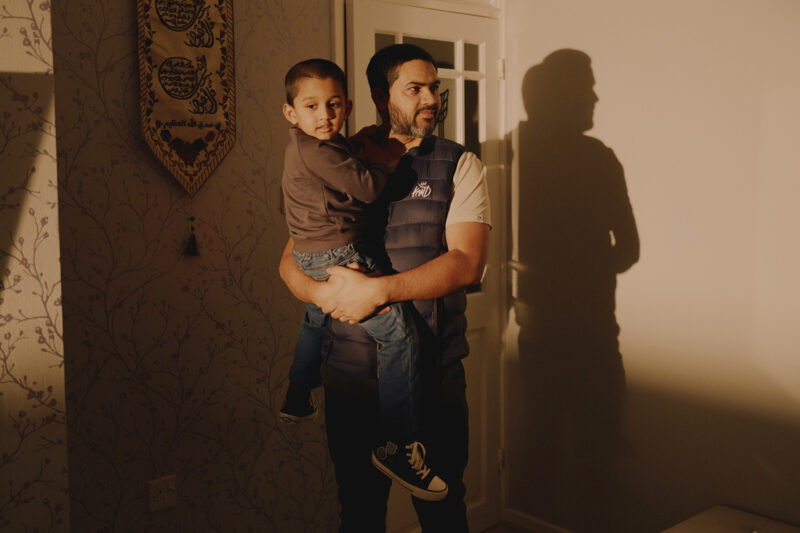

To help bridge the gap between public health bodies and local faith spaces, a new charity, Faith in Communities was created and led by Mufti Muhammed Zubair Butt. With two decades of experience working with Bradford’s mosques, Butt quickly became a trusted voice in a project many were unsure how to approach.

“We became the go-between,” he said. “Public health bodies didn’t always know how to speak to madrasas, and madrasas didn’t always have the time or resources to navigate large institutions. But we understood both worlds.”

With more than 4,500 children and 30 mosques involved between 2020 and 2024, the transformation of madrasas into active, health-promoting spaces has taken many forms. Some now begin lessons with five minutes of stretching, while others have launched Walk to Madrasa campaigns to encourage children and families to get moving before their classes start.

One mosque went as far as to declare itself a fizzy drink and pizza-free zone, while another transformed its rooftop into a playground. Football clubs, fencing classes and girls-only archery sessions have been introduced through partnerships with local sport clubs.

“What’s changed is that physical health is now part of the conversation,” said Butt. “It’s in the curriculum. It’s being taken home.”

JU:MP’s faith strand has been so successful that five other local authorities have received training based on Bradford’s model. Sport England has now extended the programme for another three years and to cover additional madrasas across Bradford and Keighley. Butt hopes the programme’s impact will stretch beyond the classroom.

“This is about long-term public health,” he said. “It’s about raising children who are not only spiritually aware but physically healthy, too. If we get it right now, we’ll have a more active and health-conscious community.”

Newsletter

Newsletter