I hold on to the memories of our flat in Uzbekistan — a family home that will always be part of who I am

My eventual homecoming, two decades after leaving the country, helped me realise this place is woven into the languages I speak, the food I eat and my history

As a child in Uzbekistan, I lived in a khrushchevka — the identical low-cost, concrete-panelled Soviet apartment blocks that lined our neighbourhood in Tashkent. These battered, brutalist buildings may seem bleak and uninviting, but they contained entire worlds inside.

Our two-bedroom flat always felt like a sanctuary, warm in the depths of winter and air-conditioned in the peaks of summer. No matter how uncertain the world felt outside, inside we found safety in the familiarity of the objects my family had accumulated over the years. Each room was crowded with heavy, varnished wooden furniture, books filling every available shelf.

The living room was the heart of our home, dominated by a towering stenka — a wall display cabinet filled with china plates and crystal glasses reserved for special visitors. There were the sagging velvet sofas, an upright piano and a small, flickering TV that showed dubbed telenovelas. Floral rugs lay on parquet floors, and lace curtains hung over the windows.

This was the home I lived in with my mum from the age of three, after she had divorced my dad. My grandma, who had separated from my grandad, lived with us along with my uncle, who was only six years older than me. A family unit brought together by unforeseen endings.

It was mostly a happy home, always full of life. Friends, neighbours and relatives who never called ahead would pop by almost every day. I remember constantly refilling the teapot and the lingering goodbyes in the hallway.

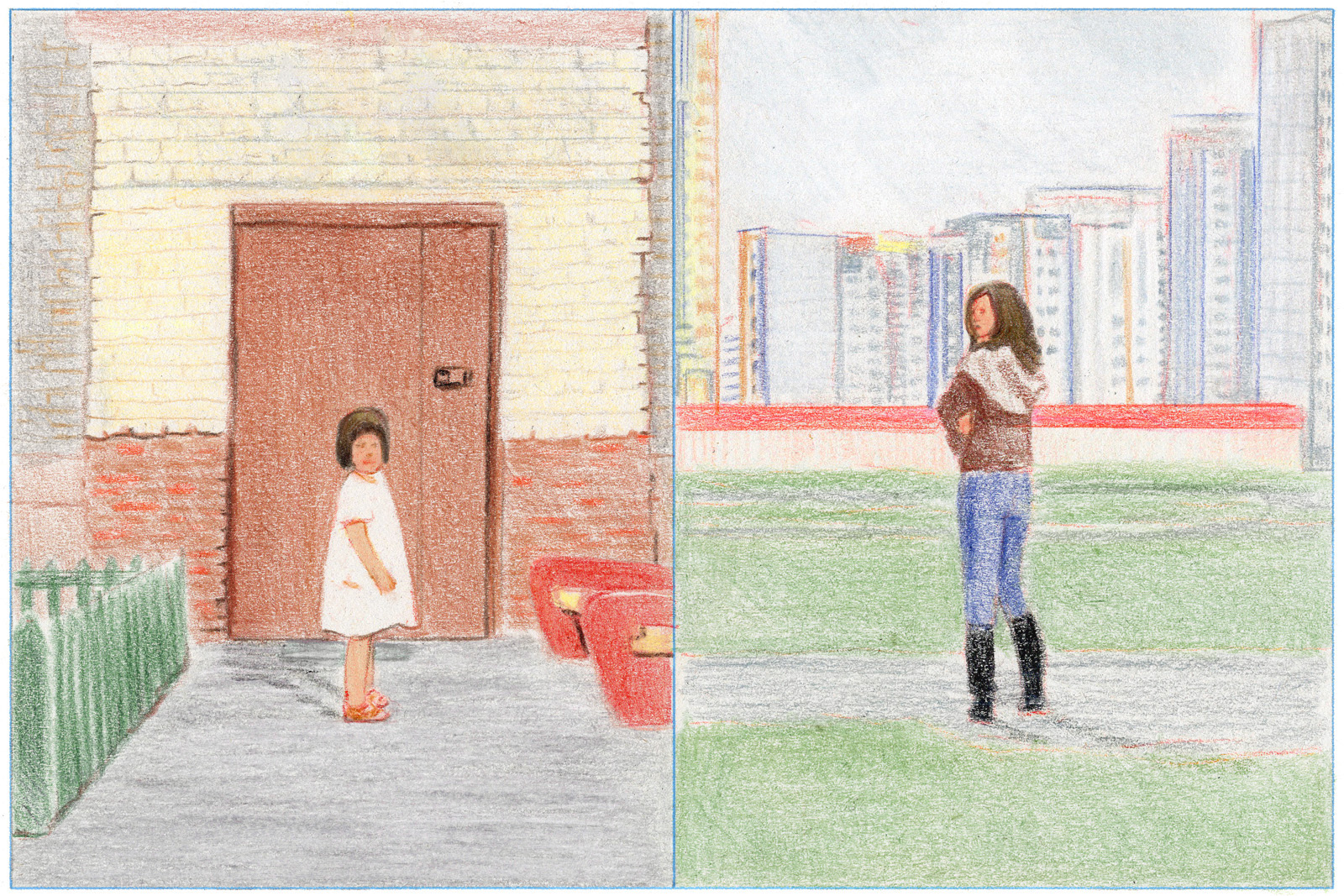

I clutch on to these memories as they have grown ever distant over the past two decades. I was nine years old in 2005 when my mum and I left Uzbekistan for London with her job in finance. At the time, many others were leaving Central Asia, seeking a different kind of life in the west, away from the economic and political difficulties that gripped many post-Soviet states in the noughties.

Yet I still yearn for those days, when we were just another Uzbek family, living our small lives inside the flat, not knowing the huge, irreversible changes lying ahead. Though life was not easy for many of us after the fall of the Soviet Union, I remember that time as one of childhood simplicity. After we moved, I held on to these memories as a doorway to the family home I knew, and to the life I might have lived had we stayed in Tashkent. They kept me steady as I navigated this new country.

The adjustment was difficult. I had to learn a new language and the unfamiliar social landscape of a new school, trying to fit in with girls whose cultural references were so different from mine. As the years went on, English replaced Russian as the language I thought and dreamed in, and my childhood friendships faded, reduced to the occasional phone call. Frequent Skype calls with relatives turned into birthday messages left on Facebook profiles.

Typical of the teenage experience, I was unsure of where I truly belonged. I felt lost and out of place, two cultures, two selves. There was a quiet ache for home. For those family gatherings, the comfort of familiar voices, the smell of my grandmother’s cooking. In London, these things only existed in memory.

It took nearly 20 years to go back to Uzbekistan, this time as a British citizen. When the country declared itself “open” in 2016, distant dreams of returning to my country of birth suddenly turned into reality.

My eventual homecoming didn’t happen until 2023. By that time, I had become estranged from my father, and that distance cast a new shadow over the trip. Yet I still went, hoping to find the part of me that stayed in our family home in Tashkent.

But the effortless sense of belonging I had known as a child seemed locked in a particular time and space, impossible to fully reclaim. I had changed. Uzbekistan had changed. Aside from a few relatives who had stayed there, I knew almost no one, and certainly no one my age. I struggled with the language. I was Uzbek, yes, but not in the way others around me were. And while it was painful to admit, the place I had once called home no longer felt like mine.

Still, there were flashes of connection: certain smells, sounds or turns of phrase that stirred something deep and familiar in me. Parts of me began to reconnect. It felt like hearing a song I had not heard in years, yet I somehow knew all the words.

One morning, I got the metro to our old flat in Chilanzar, a residential district defined by its dense clusters of brutalist apartments. I hoped I’d bump into someone I knew, that I’d feel a sense of homecoming. But I stood frozen outside the building, not knowing who lived there now — my grandmother, who had passed away years earlier, had sold the flat when we left to pay off family debts.

I could tell it wasn’t the place I had held on to in my memory. It looked smaller, unfamiliar, like a shadow of what it once was, or, perhaps, what I had imagined it to be. Not wanting to overwrite my memories, I never knocked on the door.

My life has been shaped by migration, building a new life in an unfamiliar place. But when we move countries, away from home and family, we don’t have to shed one part of ourselves to make room for the other. I understand that now. Uzbekistan will always be part of who I am. It’s woven into the languages I speak, my memories, the food I eat and my family history.

I may never stand in my family’s apartment again, but I will continue to return to it often, in the stillness of memory.

Newsletter

Newsletter