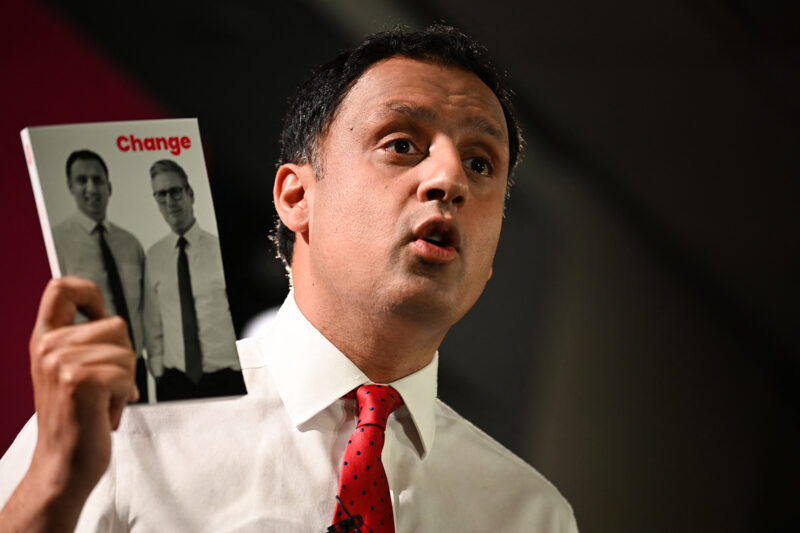

Has Labour repaired its relationship with British Muslims?

A year after Labour’s “historic break” from Muslim voters, the available data makes bleak reading for party strategists. But some see cause for optimism

Few inside the Westminster bubble had heard of Shockat Adam until a little after 3am on 5 July 2024. Attempting a pun on his name, the BBC described Adam’s victory that night over the incumbent Labour MP Jonathan Ashworth in Leicester South — a constituency that had backed Labour at every general election since 1987 — as “a bit of a Shock”.

Adam was not alone. By the time counting finished, six MPs had been elected as independents, the highest number since the second world war. Five of those had run against Labour on its own turf with explicitly pro-Gaza campaigns.

But the BBC and others in the media who used words such as “shock” and “surprise” to describe Ashworth’s defeat were not entirely correct. Thousands had already quit Labour over Gaza, including 100 local councillors. And the Labour Muslim Network had been sounding the alarm about seats such as Leicester South for months, having commissioned a poll at the start of 2024 which found that support for Labour by Muslim voters had halved. Three weeks before election day, Labour HQ was urgently sending people to shore up its votes in 13 seats.

It didn’t work. An estimated half of British Muslims who had previously voted Labour either cast their votes for other candidates on 4 July 2024 or did not vote at all, according to analysis conducted for Hyphen.

One year on, analysis of by-election results over the past 12 months, and Hyphen’s conversations with a dozen Muslim Labour figures at a range of levels within the party, suggest British Muslim voters are still reticent and distrustful for reasons that include both domestic and foreign policy.

“There has to be a recognition of the wide scale — and, I think, historic — break of trust between Muslim communities and the Labour party,” said Ali Milani, chair of the Labour Muslim Network and a former parliamentary candidate. “Whether that’s fully accepted by the most senior decision-makers in the party is for them to reflect on.”

Fourteen seats up for grabs in the May 2025 local elections were in areas with Muslim populations of 30% or more. Eight of those 14 elected independent candidates; just two backed Labour. The rest returned Tory, Green and Reform councillors.

The polls mostly took place in county council areas with relatively small Muslim communities: those 14 wards represent fewer than 1% of the 1,600 seats that were contested. But next year’s local elections will include Labour strongholds in London, the Midlands and the north of England, which could produce catastrophic results should they fail to win back Muslim voters on this scale. In London alone, Hyphen’s analysis shows 53 out of 679 wards have Muslim populations above 30%. That could be enough to threaten Labour’s control of entire councils such as Newham and Redbridge, where those seats are concentrated, if the 2025 results are repeated.

Polling and analysis company More in Common UK has twice modelled the results of a general election using a statistical modelling technique known as multi-level regression and post-stratification (or MRP). “We now have four more [parliamentary] seats being lost to independent candidates from Labour,” said Ed Hodgson, its associate director for polling and analysis. He explained, however, that this is mostly being driven by Labour losing voters to Reform, while the independent vote has stayed stable. The same modelling predicts Reform winning 180 seats, with Labour and Tories both retaining 165 MPs each.

Sabiya Khan is a Labour councillor in Bradford. “It’s been a difficult and challenging time,” she said. “You get challenged: ‘Why don’t you leave the party? So and so has left the party, and how can you remain within the party?’”

But she feels she is better placed to make change from within. “We’ve learned lessons in terms of engaging and understanding our diverse communities that we have in the 21st century and not taking communities for granted,” she said. Khan points to Labour-led Bradford council passing at least three motions calling for a ceasefire in Gaza and the strong relationship between Muslim communities and the local Labour MPs, who have all backed calls for a ceasefire in parliament.

Shabina Qayyum, a Labour councillor and cabinet member in Peterborough, concedes that the party’s relationship with Muslim communities “deteriorated” after 7 October 2023 — but she too insists that Labour is still a safe place for Muslims. “I was given a lot of support from the party both nationally and locally,” she said. “The MP has really tried to make an effort with local mosques and Muslim communities on the ground.”

The MP in question, Andrew Pakes, has raised questions in parliament about Gaza, something Qayyum argues is a credible “litmus test” of listening to the concerns of the Muslim communities in Peterborough. She also points to efforts by the government to establish a definition of Islamophobia, to tackle the cost of living crisis and to invest in public services and infrastructure, all of which she says will benefit working-class Muslim communities living in cities such as Peterborough that have high levels of deprivation.

Qayyum says the Labour party’s external relations group is working with Muslim councillors to help them rebuild trust and relationships with Muslim communities around them. For her, this means having their concerns heard on Gaza and on issues that are relevant to Muslim communities in the midst of an increasingly polarised society.

Others are less optimistic. “I don’t think they [British Muslims] see any real change coming from the Labour party,” said Khalid Mahmood, a former Labour MP who lost his seat in Birmingham to independent Ayoub Khan. Mahmood accepts that British Muslims are genuinely concerned about the war in Gaza. But he believes British Muslim organisations — he lists several — are prioritising this over issues such as the cost of living and crime because of the influence of “Islamist slash Muslim Brotherhood” politics, making it harder for the party to meet them halfway.

The Labour government has made a handful of interventions on Palestine in the last year, joining with France and Canada in May to “strongly oppose” the expansion of military operations there by the Israeli Defense Forces and calling the humanitarian situation in Gaza “intolerable”, sanctioning some settlers and their organisations and two government ministers, and engaging in talks about recognising a Palestinian state unilaterally.

But focus groups run since the election by More in Common have found that some Muslims see this as too little too late, and have little trust that Labour is actually prepared to see policies through rather than simply using incremental movements such as these to appease angry voters.

Hyphen understands that work is now happening at the highest levels of Labour to conduct comprehensive polling of British Muslims, with the hope of identifying ways to win back those who have left. One activist in the north-west said that some councillors who quit Labour to go independent had only done so under pressure from constituents, and were still hoping to rejoin the party one day.

Gaza may have been the trigger for their break from the party, but there were longer term reasons why British Muslims were disillusioned with Labour, too. “All of them, really, lived in Labour safe seats in city centres, which in many cases have been really neglected for quite a few years,” Hodgson said. Muslims in the three focus groups — two in Birmingham and one in London, all run in independent-voting seats — cited the cost of living, high street shops closing down, crime and the quality of local hospitals and services as their chief electoral concerns.

“When I asked why they had voted for who they voted for, many of them had almost forgotten that Gaza was the driving factor,” said Hodgson. “In all three of these groups, I really vividly remember saying: ‘And why did you vote for this candidate?’ And the people said: ‘Yeah, I like their policies.’” Often only when Hodgson himself brought up Gaza did voters agree that it, too, had been a key influence on votes lost by Labour to independent candidates.

There is also the question of how to engage with British Muslim communities. Labour’s relationship with the Muslim Council of Britain (MCB) continues to be non-existent on a formal level, a continuation of the policy established in 2010 by the then Conservative-Lib Dem government. In January this year, Stephen Timms, a Labour MP for east London and a junior minister, was disciplined for attending an annual leadership dinner organised by the MCB.

“We find it very strange that the British government is very clearly stating that they do not want to have any communications with the largest, most diverse, most representative body of the Muslim community,” said Dr Wajid Akhter, the council’s secretary-general. Akhter believes Labour has “a huge problem with narrative” and making its actions “match the rhetoric”. It continues, for instance, to supply weapons to Israel, he said. “When you see that kind of stark disparity between what’s being said and what’s being done, trust doesn’t just evaporate,” he said. “It turns into disgust.”

Akhter did praise the swift response of Starmer’s government to the racist riots that broke out across the UK last summer, but is concerned that not enough is being done to address their causes and tackle Islamophobia, including in parliament itself. “There are some people, MPs, whose only contribution to being elected is to stand up every month, every single time, and punch down on the [Muslim] community,” he said, referring to recent debates on banning the burqa and halal meat.

The Labour Muslim Network is calling for the government to adopt a legal definition of Islamophobia, end the ban on engagement with the Muslim Council of Britain, and support Palestine by recognising it as a state and banning arms sales to Israel. “Our plea to all levels of the party is to not abandon what has been multi generations of relationships, respect and ties to the party by doing so much more than is being done right now,” Milani said. Hyphen has approached Labour HQ for comment.

Hodgson added: “The only way, really, that Labour has a chance of persuading these voters to come back, in my opinion, is yes, they have to answer their concerns on Gaza. It can’t be seen to be siding with Israel. But more importantly, they have to show they can deliver on issues like the NHS.” Labour, he said, needs “good, authentic Muslim candidates” at an MP level who are seen as strong, effective and genuinely rooted in the local community, rather than parachuted in from London.

Bradford councillor Khan is optimistic. “I hope very much that the party listens and takes on board some of the perspectives on what’s needed to create that change, to bring us, the Labour party, closer to the communities that we serve,” she said.

Even those outside the party believe the stakes are high. “If they thought the last election was bad, then the reality is that the next one may be worse,” said Akhter. “The new generation is becoming very disenfranchised, not just with the Labour party, but sometimes with the whole party system. That’s dangerous.”

Newsletter

Newsletter