Muslim emergency workers welcome new law closing loophole on abuse

Ambulance and fire workers say criminalising abuse from the public is a worthwhile step — but that more must be done to fix internal culture

Muslim emergency workers have welcomed proposed new laws to tackle racial and religious abuse towards firefighters, ambulance staff and police responding to calls in private homes.

The measures, introduced under Labour’s crime and policing bill, seek to close the loophole that protects emergency workers from racial and religious abuse in public but not inside people’s homes.

It is not currently an offence to racially or religiously abuse another person in a private home — a gap in the law that was originally supposed to prevent people from being prosecuted for private conversations.

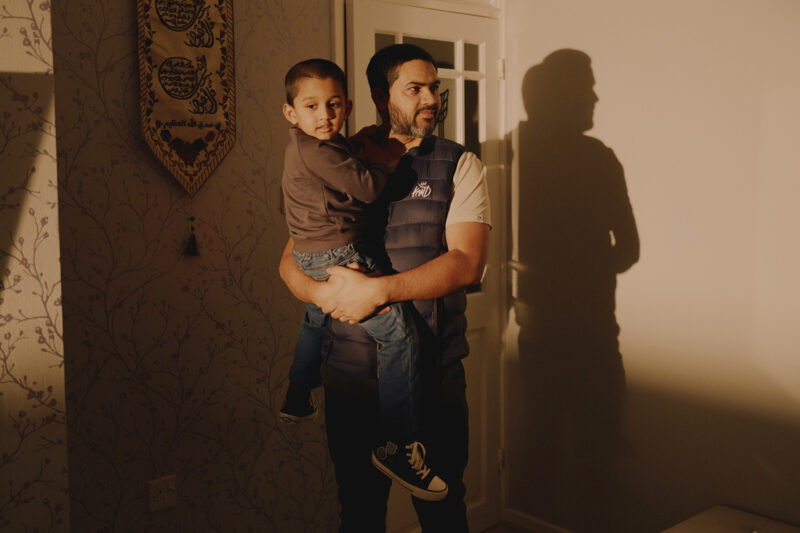

Shumel Rahman, a paramedic who has worked for the North East Ambulance Service for more than a decade, said: “Sometimes society thinks that because we’re public servants, they can treat us any way they want. Some people’s behaviour is absolutely unacceptable and hopefully this will make people think twice about their actions.”

In March, an NHS staff survey found that attacks on frontline workers had increased since 2023. In 2024 alone, about one in seven NHS staff (14%) experienced physical violence of some sort from patients, their relatives or members of the public.

Discrimination also reached its highest level in five years, with 9.25% of staff reporting such incidents involving patients and the public, and more than half saying that the abuse they faced was based on their ethnic background.

Rahman, who describes himself as a “Geordie Bangladeshi”, told Hyphen he has experienced both microaggressions and overt racism while on duty. He recalled being racially abused by the same man on two separate occasions.

The man, who was intoxicated, initially called Rahman the N-word while he and his colleague were trying to help him into an ambulance. After being warned about his behaviour, he calmed down, but once at the hospital he began shouting further racial slurs, including the P-word.

“I’m quite thick-skinned, but I thought: ‘What if it was a newly qualified paramedic? What if it was someone who wasn’t quite as robust?’” said Rahman. When he encountered the same man again a week later and was subjected to more abuse, he reported both incidents to the police.

Under the new laws, abusing emergency workers in any setting will carry a maximum sentence of two years in prison.

Uroosa Arshid, who became the UK’s first hijab-wearing firefighter when she joined Nottinghamshire Fire and Rescue Service in 2019, said: “I’m hoping this legislation will make a massive difference even if it’s just in getting information out there that actually, there are lots of different faiths, cultures and genders in these roles.”

Arshid said most interactions with the public were positive but that responses to her could be “mixed”.

“You get a lot of encouragement. Some people say: ‘I’ve never seen a female firefighter, or an Asian firefighter, or a Muslim firefighter.’ But then you do also get the negative side of it where people will just look past you and don’t really accept that you’re also a firefighter like your male colleagues.”

She added that being visibly Muslim because of her hijab brings additional safety concerns while on duty. “You’re always going into a home with caution, thinking: ‘I wonder how these people are going to respond to me. Is it going to be negative? Do I need to protect myself? How do I need to react?’ Those things are going through my mind on a constant basis — things that aren’t going through the mind of your standard straight, white, male firefighter.”

Another firefighter, who asked us not to publish his name, said he once arrived at someone’s home to carry out a fire safety check only to be called the P-word by the homeowner and told that he wasn’t welcome.

He went to sit in the fire engine while the visit took place — without challenge from any of his colleagues. “What hurt me more than anything else,” he said, “was the fact that the home fire safety check actually continued.”

He also emphasised the need for cultural change and allyship within fire stations and public services. “Only then will this legislation be effective,” he said, adding that workers who do not feel supported by colleagues may be less likely to speak out about abuse they face from the public.

Policing minister Dame Diana Johnson said: “Our emergency workers put themselves in harm’s way every day to keep us safe and they should never have to tolerate abuse due to their race or religion while simply doing their job.

“By closing this loophole, we’re sending a clear message that racial and religious abuse directed towards those who serve our communities will not be tolerated.”

Hafsa Mahumud, who trained as a paramedic and now carries out research at the University of East Anglia into racial disparities and the lack of diversity in the ambulance service, said protections against public abuse were welcome — but that emergency workers also needed better safeguards against discrimination from colleagues.

“I just don’t think that they’re doing enough and that’s partly why we have the sheer amount of problems we do within the service — because they can get away with it,” she said.

A 2023 review of NHS Ambulance trusts by the National Guardian’s Office — which supports people in raising workplace concerns — found that ambulance staff had a “fear of speaking up” amid a “cliquey” culture of “sexism, racism and homophobia”.

“We need to first look into what environment we’re trying to bring people into,” Mahumud added. “We’re trying to diversify the workforce, but we’re not trying to fix the culture of the workforce.”

Alishba Hashba, a paramedic at the North East Ambulance Service, also noted a lack of visible diversity within the profession. “I think what people view as a paramedic is an older white man,” she said, “and that’s the image that I had when I started thinking about getting into the job. Even now, I can count on one hand how many people of colour I know that work in my area.”

Hashba added that while it was “good” that the government was taking attacks on emergency workers seriously, more needed to be done to foster cultural understanding and support within the ambulance service itself.

“A lot of people just don’t understand or consider that others live differently,” she said.

Anna Parry, managing director of the Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE), said that building anti-racist, inclusive workplaces was “crucial”. “Ambulance service leaders are committed to creating psychologically safe workplaces where people are treated with dignity and respect,” she said.

Having cleared a Commons vote, the crime and policing bill had its first reading in the House of Lords earlier this month. A date is yet to be announced for its second reading there.

Newsletter

Newsletter