Faith-based charities are ‘better at convincing people to accept help’

Panellists from the National Zakat Foundation and Christian, Jewish and Sikh charities discussed the role of faith in tackling poverty

Faith-based charities are often better placed to convince people to accept help than their secular counterparts, representatives of four such organisations told a panel on Wednesday.

The discussion on faith, charity and the cost of living was hosted by the Institute for the Impact of Faith in Life (IIFL) on Wednesday. Guests included the chief executive of the National Zakat Foundation — which distributes zakat in the UK — as well as speakers from Christian, Jewish and Sikh charities.

“People know that they are a part of a community, and they give when they can give and they receive when they need support,” said Sharon Daniels, head of social responsibility at the United Synagogue, the largest umbrella body for Orthodox Judaism in the UK. “That’s what it means to be part of a community rather than a charity recipient. I think that’s a really big distinction — and that comes with a lot of dignity and is important for people.”

Panellists from the other organisations, including Christians Against Poverty and the Nishkam Sikh Welfare and Awareness Team, agreed.

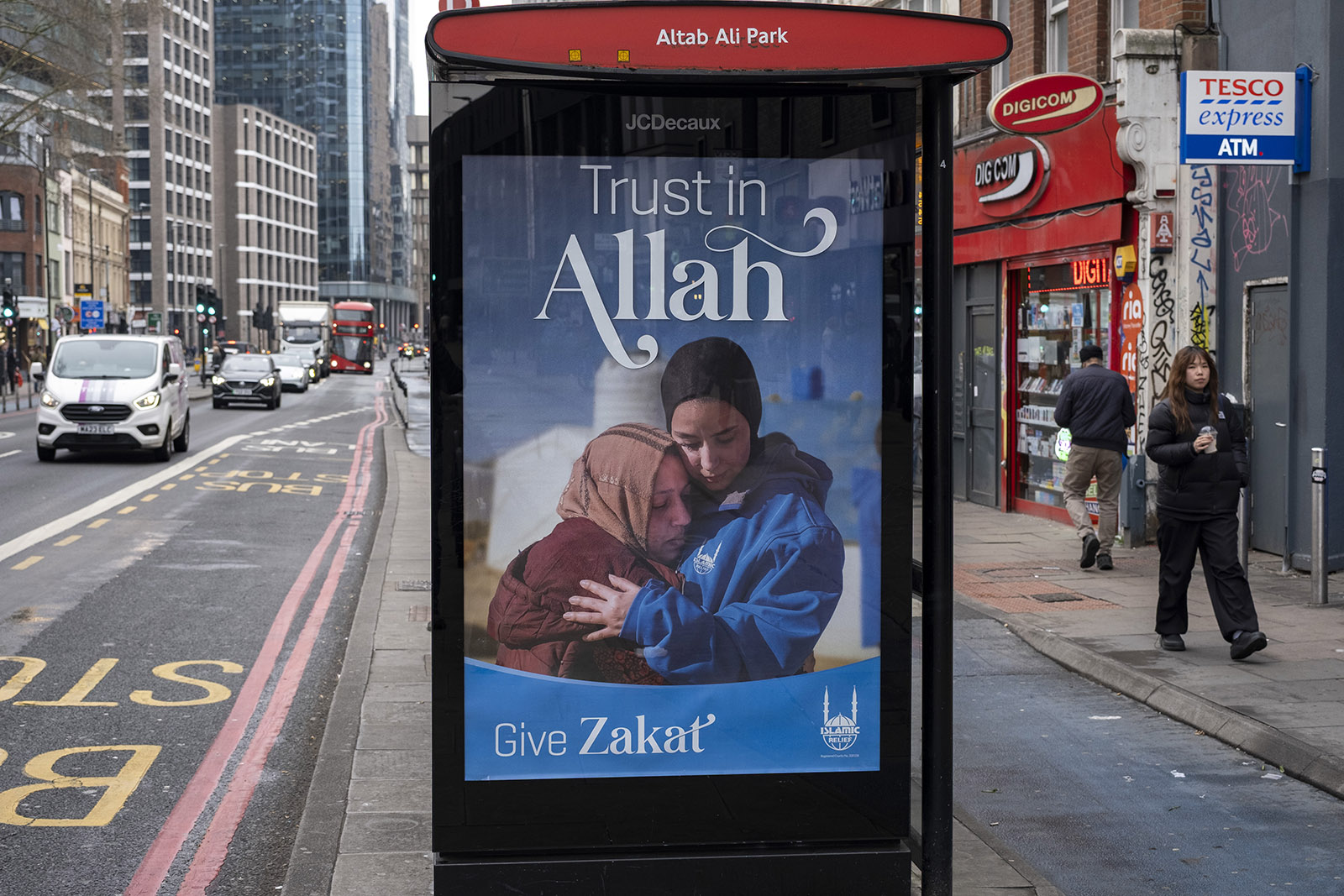

“Faith builds infrastructure in communities,” said Sohail Hanif of the National Zakat Foundation. “It’s very hard to imagine a Britain without its churches and its mosques, its synagogues and its temples. This is where you reach people whose needs are not otherwise visible. Faith infrastructure is what makes faith such a powerful force of community support, solidarity and welfare.”

Recent research suggests that a lack of reciprocity between service users and providers can contribute to shame and stigma around accessing material support.

However, Hanif observed that Islam, like other religious traditions, provides an alternative to the entrenched model of a passive charity recipient.

“The whole notion of zakat flips the script,” Hanif said. “We believe that the zakat is the right of the needy over the rich. It is the rich person who is needy. They need to purify their wealth by giving it to someone who is in need of it. There is a shifting in power.”

Commitment to recipients’ dignity also motivated the foundation’s move toward transferring cash directly to recipients.

“The idea is we give people the full dignity of choice. We believe they know the best way to look after their own needs,” Hanif said. “We don’t treat them as suspect, that all they can do is have this thing we’ve given them because we don’t trust them to make choices for themselves.”

For Hanif, like other panel participants, the current cost of living crisis, coupled with more than a decade of austerity, has left faith-based charities picking up the pieces of destroyed social services.

“Whether we like it or not, our public services are crumbling — they’re not where we’d like them to be, they are not where they were,” he said. “But maybe this is an opportunity to rediscover a more ancient way of living, which is community. People have always felt responsible for their neighbours but this has been weakened by our political structures.

“Those structures are not keeping up with what we’d like them to and I think faith is now required to educate each other that it was always our job to look after each other. If we create model networks and systems, we might not just help people today but we might reintroduce people to a way more wholesome way of living.”

The panel participants also said that their jobs were made harder because their organisations were often met with scepticism from secular authorities and organisations.

“We are all committed to our communities, but a misconception we are often met with is that we are just do-gooders who don’t know what they’re doing,” said Graeme McMeekin from Christians Against Poverty.

Research suggests that Muslim charities may even face the additional hurdle of being treated as security threats while trying to help people.

“The standard narrative deriving from politicians, policymakers and media is that Muslim humanitarian organisations and charities are a cover for terrorist financing,” wrote Samantha May, a senior lecturer at the University of Aberdeen, in her paper Muslim Charity in the United Kingdom: Between Counterterror and Social Integration. She pointed out the struggle of some charities to access banking services, which “affected the whole spectrum of the charity sector but have excessively affected Muslim charities specifically”.

Nonetheless, a recent debate in the House of Commons on changing tax rules for listed religious buildings saw MPs extol the benefits of faith-based charity work for society as a whole.

“I am a Muslim, and I volunteer for a Sikh charity, the Midland Langar Seva Society, which operates out of a church and serves people of all faiths and no faith,” independent MP Shockat Adam told the chamber last month. “That is what community looks like and what Britain looks like — it is not an island of strangers.”

Newsletter

Newsletter