Photographer Asma Elbadawi on ‘being seen but not seen, as a Muslim woman’

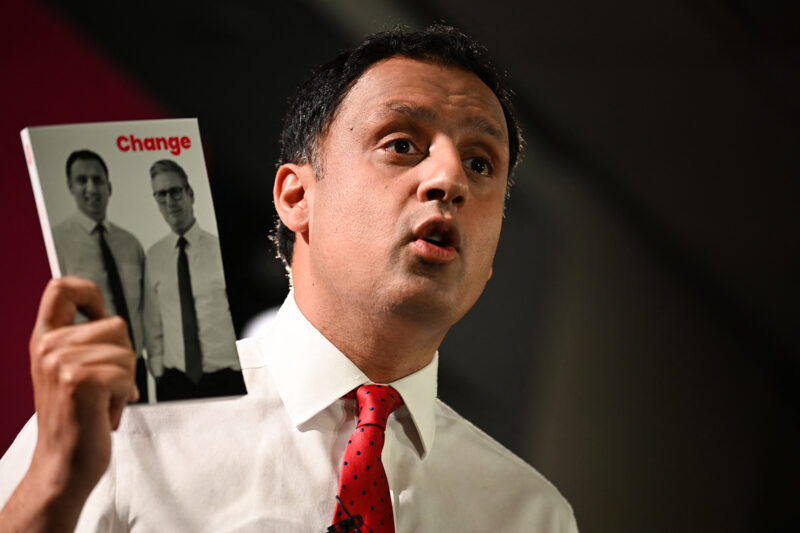

The winner of the BJP’s Female in Focus x Nikon award is known for her self-portraits critiquing the expectations set on women

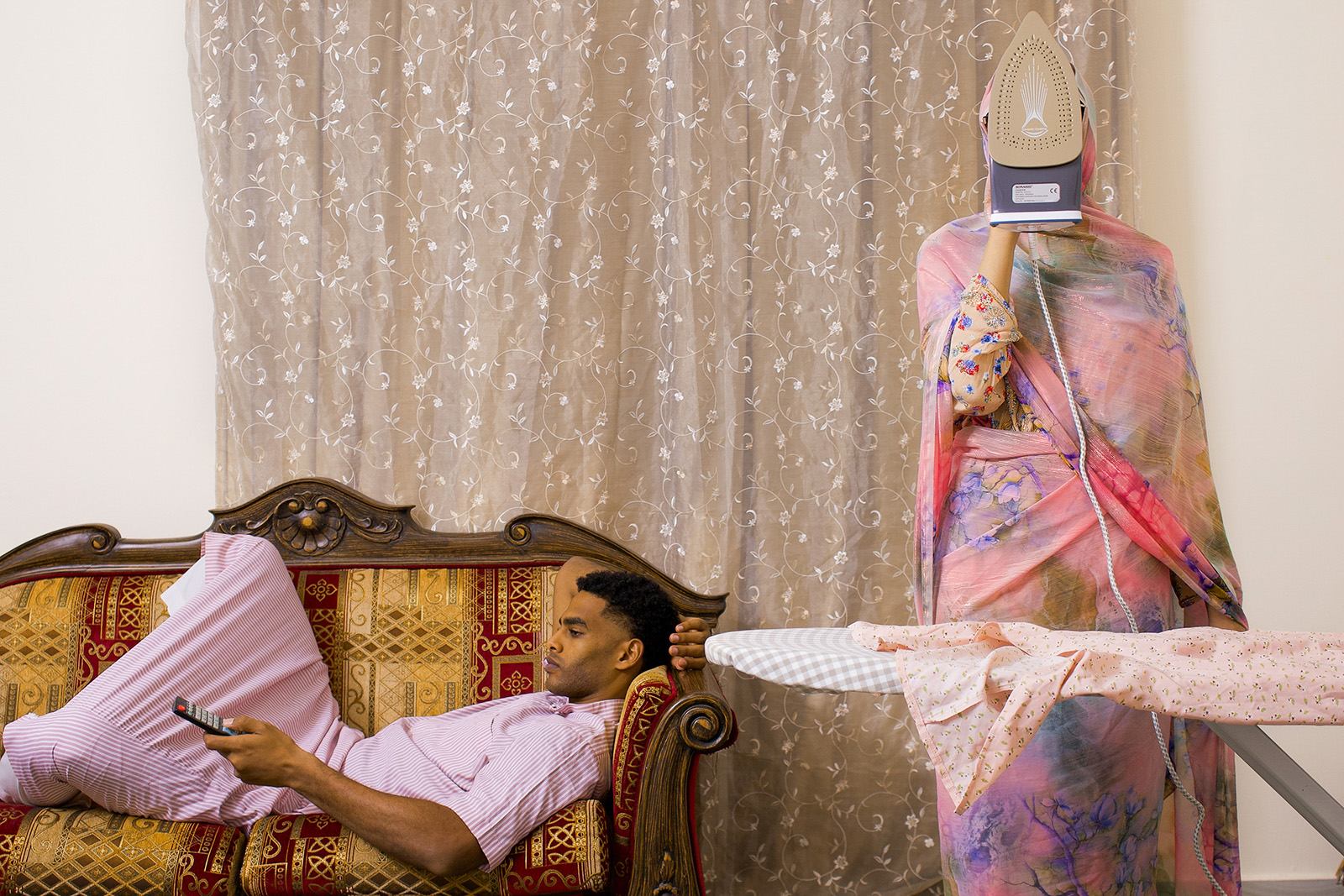

In British-Sudanese photographer Asma Elbadawi’s Unseen Yet Seen series, a husband and wife pose in front of a backdrop of embroidered curtains. Occasionally, an orange chest of drawers or a wooden table appear in the frame, holding a lamp, a camera, or the ubiquitous box of chocolates that, in many homes, is often recycled to hold contents other than those promised on the tin.

In every image, the wife’s face is concealed by an accessory or an object. In the background of one photo, the husband reclines on the sofa with a TV remote in his hand.

The concept behind Elbadawi’s photographs — self-portraits in which she appears as the wife figure — developed while she was looking at images she had taken as part of her own wedding shoot. In one picture, she had instinctively covered her face with her hat. The image stood out for its potential to elicit a conversation about “the middle ground of being seen but not seen, as a Muslim woman,” she says.

Elbadawi, who in addition to her photography, is a basketball player, sports inclusivity consultant and spoken word poet, is best known for her involvement with a campaign petitioning the International Basketball Association to lift its restrictions on the hijab and religious headwear in 2017. “I don’t think anyone ever opened the rule book and actually looked to see if we were allowed to play or not,” she says, explaining that the effort came about after a friend, the American-Bosnian player Indira Kaljo, was banned from professional basketball when she started wearing the hijab.

“The goal was to change the rule. I saw it as a huge storytelling project,” she explains. “Why did I never think about going professional? Why did I never think that could be my path? It was because I wasn’t told stories of women who did these things. They were invisible.”

The possibility of encompassing several identities — sportsperson, wife, hijabi — is the subject of an image that won the 2024 British Journal of Photography’s Female in Focus x Nikon award. Elbadawi returns to the domestic setting of her self-portraits, appearing in a vintage wedding dress as she irons a pair of parrot-green tracksuit trousers. Through the juxtaposition, she says, “I was critiquing society as a whole: the western world, as well as the Arab world, the community that I grew up in,” adding that she created the image while pregnant. It speaks to “the expectations that are placed on women, and what is deemed acceptable to continue doing, and what should now be a hobby, after becoming a mum,” Elbadawi says.

It was while studying at the University of Sunderland that Elbadawi first developed an interest in photography. Tasked to take pictures for a day on a disposable camera, she captured herself as she engaged in quotidian tasks: taking the train, waiting for the bus, walking on the street. It was her first visual exploration of what it means to be a Muslim woman in western society.

An exposure to the work of Shirin Neshat and Alec Soth shaped the development of Elbadawi’s early aesthetic. Clothing — wedding dresses, athletic wear — are not mere costumes, but embody broader symbolism. She is drawn to evoking a feeling of nostalgia, a sense that viewers might have seen the image before “in their grandmother’s album” she says, pointing to photographs in which the home is not picture-perfect. “There’s somebody laying on the floor. There’s a cup of tea on the side. It almost shows real life. I tend to recreate those feelings.”

On family trips to Sudan, the home was often the only context for Elbadawi’s practice. “You couldn’t really photograph in public, so it was always easier to photograph in domestic spaces,” she says, though even a few of those images couldn’t be shown to an outside audience. “Some of the women were not dressed in the way they would normally be seen in public, because they wear a hijab. But I got to know where I came from when I was taking those specific images, because it was constant — every time I went to Sudan, I had the camera with me.”

Elbadawi’s recent work is intended to spark more questions than answers. One reading of the Unseen Yet Seen series might suggest a commentary on the invisible labour of wives and mothers. Elbadawi explains that the images in which her face is hidden stem from what she calls the “sacred space” that exists in the home: a kind of intimacy and privacy that is safeguarded in certain cultures.

“Sometimes, not being seen is by choice. When we look at it from an Islamic perspective, it’s that delicate balance: what do you keep private and what do you make public?” she says. “I’ve been on social media for a long time, and I’ve had to show up as a specific kind of person, whether I’m talking about activism, women wearing the hijab in sports, or performing my poetry. There’s this visibility that exists in my everyday life. But in that space, I could just be Asma.”

Elbadawi believes that choosing to cover your beauty is a “form of resistance in a world that wants to see your beauty and values you based on your beauty”.

“I don’t want to be seen all the time, in the way that you want to see me,” she says. “You can see that I play sports or have a family, but you can’t have the one thing that is the most important, which is my modesty.”

Female in Focus is showing at the Glasgow Gallery of Photography, 26 June-27 July.

Newsletter

Newsletter