NHS pays ethnic minority workers from overseas less than white colleagues

Asian migrant workers are 22% less likely to be high earners than their white, UK-born colleagues, while Black migrant workers are 30% less likely

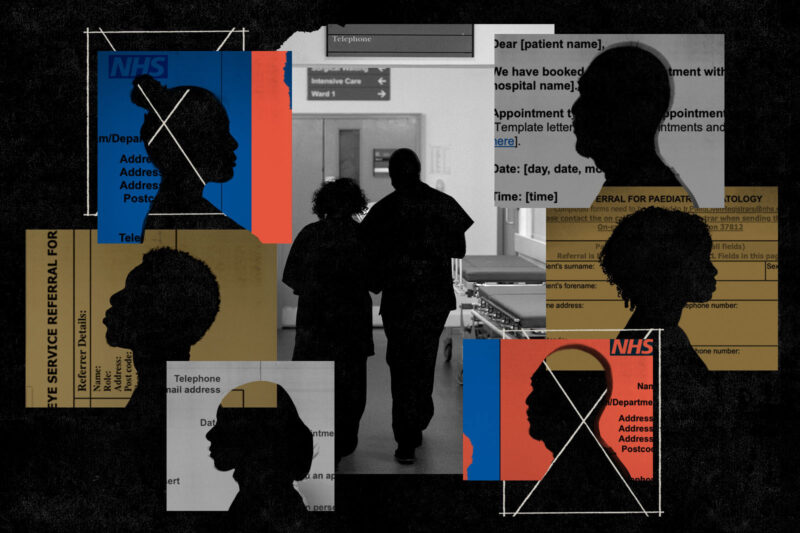

Ethnic minority NHS staff who were born overseas earn less than their white colleagues even when they have the same qualifications and experience, the most comprehensive study ever carried out on the subject has found.

The research, published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, found that migrant Asian and Black healthcare workers were less likely to reach higher income pay bands than their UK-born white colleagues. It is the first time a link has been established between migration status, ethnicity and career progression in the NHS.

The study of more than 5,700 healthcare workers, which included nurses, midwives and allied health professionals, found this to be true even after adjusting for education, job role and how long they have been professionally qualified.

Black workers born outside of the UK were 30% less likely than white UK-born colleagues with the same qualifications and experience to be in the top two pay bands 30 years after qualifying, while workers from Asian backgrounds born outside the UK were 22% less likely than UK-born white colleagues to be in the top two bands after the same period.

Related content

In the NHS, all staff apart from doctors and dentists are categorised into pay bands based on their roles and responsibilities. Employees in band five earn £31,049 to £37,796 a year, while those in the highest grade of band nine may earn up to £125,000. The study categorised roles at band eight and above as senior.

Professor Manish Pareek, clinical professor in infectious diseases, director of the Development Centre for Population Health at the University of Leicester and an author of the study, said: “Ethnic minority healthcare workers represent over a third of staff at NHS pay band five, but their presence drops sharply to just 10% in senior roles.

“This lack of diversity in leadership limits influence over key workplace decisions such as pay, scheduling and policy, which may contribute to a less supportive environment for ethnic minority staff. These inequalities risk driving higher attrition rates amid the NHS’s ongoing staffing challenges.”

Researchers said migrant workers face specific challenges, including having limited professional networks, some international qualifications not being recognised in the UK, and restricted access to training opportunities.

The authors said these issues were compounded by the lack of ethnic minority staff in leadership positions, which means they have less influence over management decisions regarding policy and workplace culture.

Related content

“For instance, restrictions on certain hairstyles for workers (e.g. dreadlocks, braids) are supposedly creating policies that apply to all employees, but in practice have a disproportionate impact on Black culture,” the authors wrote.

Additionally, ethnic minority staff — both from the UK and overseas — were between 1.2 and two times as likely as white staff to be subjected to formal disciplinary processes in 70% of NHS trusts.

“Overseas healthcare workers are vital to the NHS,” said Stuart Tuckwood, national nursing officer at the union Unison — which represents NHS nurses, midwives, paramedics and health visitors. “Yet all too often, their skills and experience are undervalued and not given recognition. Many are placed at the bottom of pay bands and facing barriers to career progression.

“NHS employers must fairly value the knowledge and expertise of international staff, and tackle bias and racism within the health service.”

Dr Shehla Imtiaz-Umer, director of advocacy at the British Islamic Medical Association, said: “Unfortunately, inequity within the NHS workforce is not new. Decades of data have evidenced the persistence of systemic racism — issues that are further magnified for internationally qualified doctors.

“These colleagues overcome innumerable barriers to contribute to the NHS. They are essential to its daily functioning, yet continue to face systemic pay disparities, discrimination, and limited career progression. What must change is how we respond: with urgency, transparency, and accountability. Continued inaction is not an option.”

Hyphen has approached NHS England for comment.

Newsletter

Newsletter