The crisis of Muslim burials in Europe

A critical lack of graves and expensive repatriations mean the problem of how to bury growing numbers of Muslim dead has reached a tipping point

In 2020, Sümbül Tarakçilar’s 40-year-old brother Ali died in Hamburg after a long battle with ill health. Most of his relatives have been buried in their native Turkey, but Ali — whose family preferred not to use his real name — was clear in the weeks before his death that he wanted to be laid to rest in Germany, the country he’d lived in most of his life, where his two young children might visit him regularly.

Immediately after Ali’s death, his sister requested a Muslim burial plot from the local municipality. Sümbül hoped she could arrange for him to be buried the following day, in keeping with Islamic tradition, but local authorities responded explaining there was a waiting list for all three local cemeteries with Muslim sections. They could not say how long it would be until a spot became available.

“You feel like your relative is lying there being tortured,” Sümbül said, explaining the process of waiting for a grave. “You feel as though you are being tortured too, you are filled up with guilt.”

Europe’s Muslim population, which was estimated to be more than 25 million in 2016, is facing a crisis in burials. Bereaved relatives in countries even with large Muslim minorities — such as Germany, Spain, France and Italy — either have to pay thousands of euros to repatriate their dead to Muslim majority countries or endure long waits for the few plots available in European cemeteries where bodies are buried in keeping with Islamic traditions, perpendicular to Mecca and in burial shrouds. Even in areas where appropriate graves are available, local bureaucratic processes can delay the burial process, making it impossible to be buried within 24 hours as recommended in the Qur’an.

Related content

Özgür Uludağ, a funeral parlour director in Hamburg, has a PhD in the funeral preferences of German Muslims. He says that while older generations still prefer to be buried in their home countries, younger people are increasingly choosing to be laid to rest in Europe so that their families can visit their graves. But the lack of Muslim plots means families are forced to wait, or bury their loved ones miles away. “It delays you from processing what has happened and moving through the grieving process,” said Sümbül.

There is no Europe-wide data on available Muslim graves: information about burial plots is kept at municipal or even parish level and the numbers vary frequently. The size of a community also makes a difference. Major cities often have more space for Muslim graves, while smaller settlements have much less capacity. Hamburg, for example, has five cemeteries with Muslim sections, while the town of Geestland 100km away has just four Muslim grave plots.

Hyphen has, however, spoken with funeral industry experts serving communities in Germany, Spain, France, Italy and the UK who say scarcity and expense are growing problems for Muslims seeking to bury their dead. Security is also an issue and graves in several countries have been vandalised by far-right activists. As the continent’s Muslim population is forecast to double by 2050, there is an urgent need to find solutions for the crisis in Islamic burials across Europe.

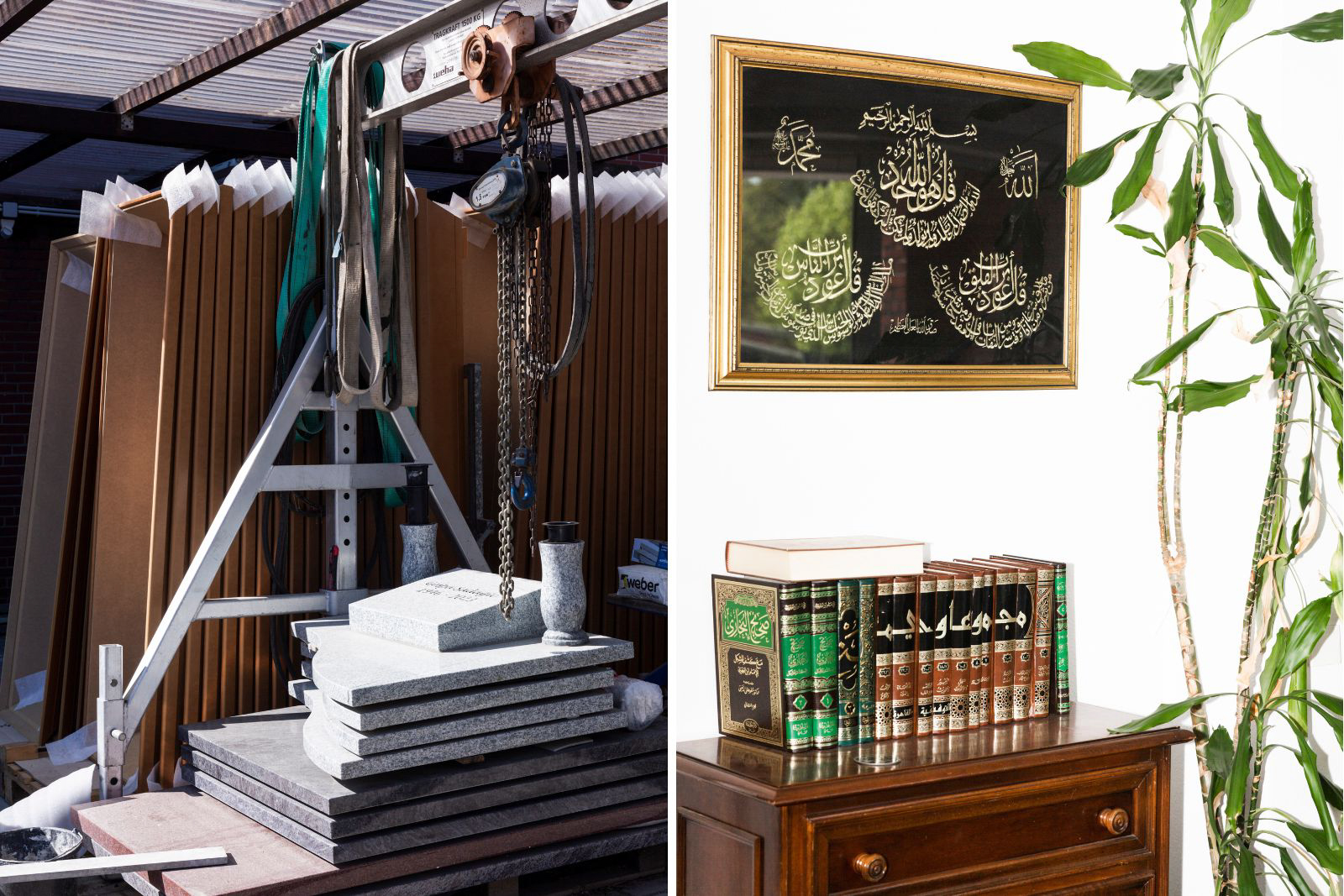

Uludağ and his sister Vildane run Uludag Cenaze, a Muslim funeral parlour in Horn, east Hamburg — one of only two in the city. The firm assisted Sümbül and her family after her brother’s death. Uludağ says the difficulty the family experienced burying Ali is far from unusual. It can take between four and 10 days after a death to secure a plot in Germany, which is one of the main reasons Uludağ says 90% of his clients are buried overseas. “We’re actually more of a transportation company than an undertaking company,” he said.

Germany’s largest and most established Muslim community is of Turkish origin. It has developed its own repatriation system for its dead. Mosques cooperate with the Turkish embassy to send bodies back quickly; specialist insurance plans shield families from high costs. According to Uludağ, the process is now so efficient that a body can be taken to a mosque then sent to Turkey within a matter of hours.

Newer Muslim communities don’t have this infrastructure and as younger Muslims who’ve lived in Germany all their lives increasingly want to be buried there, pressure is growing on a scant number of plots.

There are currently 327 graveyards serving Germany’s five million Muslims. Most sit as specialised sections within larger Christian cemeteries, which Uludağ explains inevitably means Muslim burials depend on the working practices of their hosts. If there’s a death on a Friday afternoon, assuming there’s no waiting list, Christian weekend hours mean the earliest a family can speak to someone about a plot will be Monday. The earliest a funeral can be held for a Friday death will be Tuesday.

There are other obstacles. Some German municipalities don’t allow burials in shrouds, meaning families sometimes have to travel long distances to find an appropriate grave, a process that can prove distressing. Even if people are not particularly religious in their day-to-day lives, faith-based rituals often become a source of comfort during times of loss, Uludağ says.

Unlike Catholicism, Protestantism and Judaism, Islam is not an official state religion in Germany and so Muslims need special permission to run cemeteries. The Muslim community in Wuppertal, western Germany, for example, has been applying for permission to open a new cemetery for more than 15 years but has still not been able to cut through the red tape to establish one.

The right to religious freedom enshrined in the constitutions of most European countries, including Germany, Spain and Italy, should guarantee Muslims a burial fitting with their beliefs. However, board members of the European Federation of Funeral Services say citizens seeking Muslim burials face problems across the region. In Italy and Greece most graves are reserved for Catholic and Orthodox burials, and many cemeteries are running out of space entirely. In France, cemeteries are secular by law, which means Muslim graveyards are not allowed except for in some regions, such as Strasbourg.

Spain has some of the oldest Muslim graves in Europe. In Andalucia, burial sites date back to the 13th century, when the region was under Muslim rule. Today, only 35 out of the country’s 17,850 cemeteries have Muslim plots and five regions — Asturias, Cantabria, Castilla-La Mancha, Galicia, and Extremadura — have no capacity for Muslim burials at all.

Lahcen Fal, 56, moved to Spain from Morocco 30 years ago and now lives in Madrid where he works as a cleaner. When his nine-month-old daughter died earlier this year with a congenital disorder, he struggled to find anywhere to bury her. Griñón, the nearest cemetery with a Muslim section, has been full since the pandemic — although an expansion is planned for later this year — and while the family considered repatriating her body to Morocco, they didn’t have insurance and couldn’t afford the €7,000 fee.

It hadn’t occurred to Fal that he wouldn’t be able to bury his baby in Madrid. “We’re in the capital of Spain, and there are no [Muslim] cemeteries. I was born in Casablanca and there we’ve got spaces for Jews, for Christians. I don’t understand it at all,” he said. The closest spot they could find was in Burgos, a three-hour drive away. While he’d like to visit his daughter’s grave more often, Fal doesn’t know the next time he’ll be able to afford the time and money to make the trip.

Maysoun Douas is head of the Madrid-based association Entierro Digno (Dignified Burial), which was founded in 2023 to campaign for Muslim citizens’ right to Islamic burial. She explains that the Spanish regions that have Muslim cemeteries fought to have them.

“Even during [general Francisco] Franco’s dictatorship, when we didn’t have a democracy and religious freedom, there were Muslim cemeteries,” Douas said. She finds it remarkable that despite Spain’s shift toward religious freedom, politicians are not prioritising the resolution of this crisis in burial spaces facing their non-Christian citizens. “Many funeral homes lack awareness and training on Muslim burials and don’t ask families about their needs,” she said.

In Vigo, south-west Galicia, Muslim organisations have been trying to buy land to create a private cemetery since 2016. Abdel el Aziri, who heads the Islamic Cultural Centre of Vigo, says that while they have now finally received the green light from city hall, they face roadblocks from the local environmental department, which claim that as the land is located in mountainous terrain, it requires additional administrative approval. The real reason for the delay, Aziri suspects, is that local politicians fear being attacked or losing votes for granting Muslims burial spaces.

“For the second and third generation of Muslims who were born here in Galicia this is their land, they don’t know any other place, and they have the right to be close to their families,” Aziri said.

Rather than waiting for municipalities to find solutions, some independent funeral homes are trying to meet the needs of Muslim clients directly. At the private Alsalam Muslim cemetery in Valencia, a perpetual adult burial plot costs €3,100, with an option of a five-year lease for €1,089. Only 20% of the cemetery’s six hectares are currently occupied. It offers lower prices to Muslim families, removing the yearly €235 maintenance fee charged to non-Muslim cemetery clients.

The Catalonia region hosts the highest number of Muslim citizens in Spain —- more than 600,000 in 2024. Its capital Barcelona is home to about 300,000 Muslims. The Barcelona municipality offers only 330 Muslim burial units, although it plans to create space for 186 more by the end of this year. Miquel Trepat Celis, director general of Cementeris de Barcelona, says any hope of meeting the demand for Muslim burial spaces comes down to two crucial factors: political will and space. “Once you start providing the services it has to be sustainable and continuous, and that commitment holds some municipalities back,” he said.

Ali was eventually buried a week after his death in a cemetery near his home in Hamburg. The experience caused Sümbül to reflect deeply on plans for her own death. Her son wants her buried near his home in Germany, but she’s decided she would like to be laid to rest near her mother’s grave in Izmir, Turkey. “All the bureaucracy and paperwork holds you back from being able to grieve properly,” she said. “It is only once the body is buried that acceptance can begin and life can finally start to move forwards.”

Newsletter

Newsletter