Alia Syed on using experimental film-making to explore issues of representation

Her latest exhibition, showing at Glasgow’s Centre for Contemporary Arts, draws on oral history from the city’s South Asian diaspora

Pasted on a wall in one of the rooms of Glasgow’s Centre for Contemporary Arts (CCA) is a patchwork wallpaper. White text is intermittently projected onto the wall, showing words taken from oral histories by the visual artist and experimental film-maker Alia Syed.

Syed began interviewing first and second-generation members of the South Asian community in Glasgow, where she lives, back in 2016, and found wallpaper to be a common physical reference point for many of those she spoke to. Some recalled encountering embossed wallpaper with abstract and kitsch designs for the first time when they came to the UK in the 1960s and 1970s. “There were memories of just getting lost in the patterns,” Syed says.

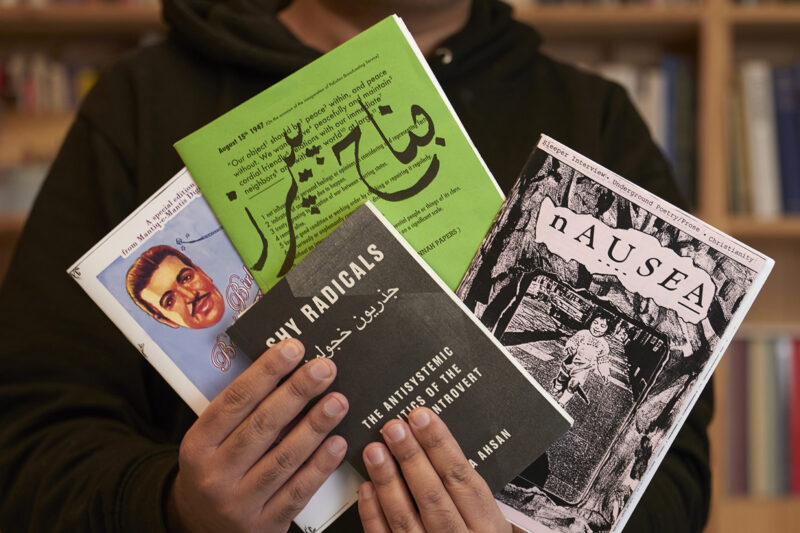

Spanning works of film shot on 16mm, photography and sound, Syed’s current exhibition, The Ring in the Fish, draws on fragments from these conversations as well as workshops she held with Muslim women’s groups around the city. Participants shared recollections and the material objects that constituted their early lives and emigration — a handwritten journal of Urdu poetry, a 1,000 rupee bill given as an Eid gift and kept in a wallet for more than 30 years, a silver bracelet passed on as a family heirloom. The scale of the exhibition ranges “from the intimate to the iconic”, Syed says. “I love the smallness of the family photographs in contrast to the size of the projections.”

Over the course of her 30-year career, Syed — whose work has been shown at Tate Modern, the Museum of Modern Art in New York and Madrid’s Reina Sofía — has explored language, history and memory, often based on South Asian identity and the legacies of colonialism. “How do we look, how do we appropriate, how do we construct meaning?” are the central questions that she says have informed her practice.

Syed was born in 1964 to a Welsh mother and a father from Hyderabad in southern India, by way of Karachi, Pakistan, where he received his postgraduate education in the years following the partition of British India. She grew up visiting family in both countries.

In the 1980s, at what is now the University of East London, Syed’s first encounter with film occurred through the 16mm cameras in the video department. Her fascination stemmed from childhood experience in mechanics nurtured by her physicist father. The medium offered a way to combine her interest in sound, images and the written word. During her postgraduate degree at the Slade School of Fine Art, she was part of the London Filmmakers Co-op, and was exposed to avant-garde films and the formative works of John Akomfrah, Isaac Julien, Trinh T Min-ha and Prathiba Parmer.

“I got very engaged in ideas of representation,” she says. “How you look and who looks at whom is at the forefront of growing up in a Muslim culture or any traditional culture. The notion of a free, devouring gaze only becomes something that is part of capitalism. Otherwise there is an ethics of looking that is always present, that you become aware of. That is essentially what experimental film-making is about: issues of representation and how to combat this notion of the all-powerful, all-consuming eye.”

The Ring in the Fish takes its name from Scottish folklore associated with Saint Mungo, the patron saint of Glasgow. Syed was inspired by the story of Queen Languoreth, who is given a ring by her husband, the medieval king Rhydderch Hael. She gifts the ring to a knight, and the king suspects her of infidelity. Saint Mungo retrieves the ring from the mouth of a fish and saves the queen from a death sentence.

“I like the story because of this notion of fidelity. Migrant communities are often accused of not being faithful or having fidelity to the so-called host country,” Syed says. “But also, the whole idea in all of the stories is one of transformation. The thing that struck me about many people from India and Pakistan was that they could reinvent themselves.

“Some working-class communities who came over became very wealthy. Class is upturned through migration, not only in relation to each other and the structures within the subcontinent, but also in relation to white British culture.”

Syed’s latest work interrogates notions of belonging in the broader context of a city whose material presence is suffused with echoes of Britain’s imperial past. “So much of the built environment of Glasgow is a byproduct of the slave trade and the wealth that comes from colonial India into Britain,” she explains. “All of these buildings that we continually look at in awe are the product of the wealth that was accrued and stolen from many different countries.”

In the film The Dhaba, showing at the CCA, Mr Bhari, a retired bus conductor and driver, speaks of his experience of racism in the 1970s, not long after Enoch Powell delivered the Rivers of Blood speech in 1968 in which he denounced immigration from Britain’s former colonies.

“To be abused, that was day-to-day,” Bhari tells Syed in the film. His words are heard over footage of the statue of Frederick Roberts, a Victorian general and colonial official responsible for quelling what the inscription on the structure in Kelvingrove Park, Glasgow, describes as “mutinies” by Indian resistance groups. Sikhs who served in the British Indian army are depicted beneath him, holding the general aloft.

“I wanted people to think about the voice and the story in relation to the city,” Syed says. By focusing on the Indian figures below Roberts, Syed reappropriates colonial imagery as a way to disrupt the statue’s messaging. “The people who are at the bottom appear at the top.”

The Ring in the Fish is showing at the Glasgow CCA until 26 July.

Newsletter

Newsletter