Halal meets tayib: how an Oxfordshire farm prepares for qurbani

Sustainability and faith lie at the heart of the Radwan family’s Willowbrook Farm

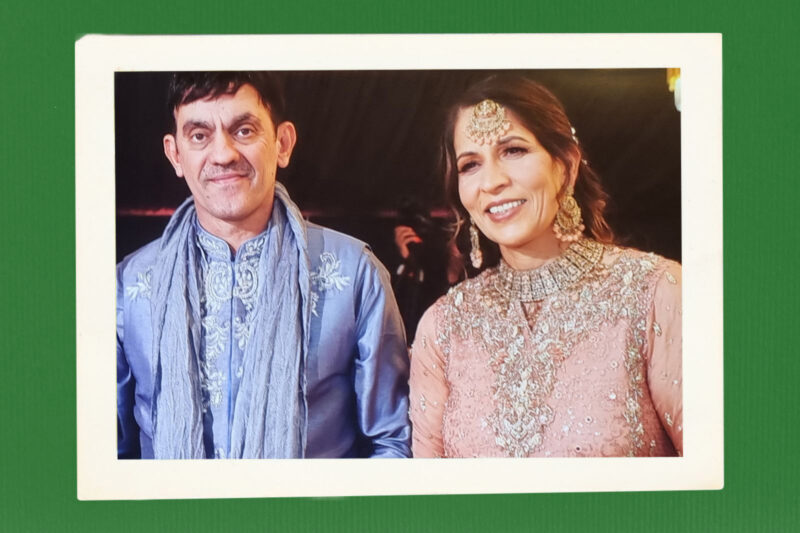

Tucked within the rolling hills of Oxfordshire sits Willowbrook Farm, the UK’s first halal and tayib farm. It’s a humid May day, just over a week before Eid al-Adha, and 62-year-old Lutfi Radwan is busy prepping animals for qurbani, putting together the final touches for the celebration. Gripping a power saw with practised ease, he carves into a fresh length of wood.

Muslims around the world have started preparation for Eid-al-Adha and qurbani, commemorating Prophet Ibrahim’s unwavering faith as he prepared to sacrifice his son in devotion to Allah. Qurbani, a sacrifice of livestock, is a spiritual echo of obedience and humility. The meat from the sacrificed animal is divided into thirds: one-third is kept, the other distributed to family and friends and the rest is given to people in need.

Although exact numbers are not publicly available, the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board estimates that each year, tens of thousands of animals — primarily small goats and sheep — are purchased for qurbani in the UK.

Radwan, who co-founded the 45-acre farm with his wife Ruby in 2002, works with his sons Ali, 20, Khalil and his wife Lamia, both 31. From the early hours of the morning each day they tend to the animals — around 1,000 chickens, 120 sheep, 24 guinea fowl, 10 goats, seven ducks, a horse and an alpaca named Alpacacino.

The Radwan family founded the farm based on the balance of sustainability, ethics and Islam, where halal meets tayib — meaning pure and wholesome. Willowbrook emphasises environmentally conscious practices such as using animal waste to fertilise the land, managing sustainable flock sizes and ensuring the animals’ welfare and dignity from the start to the end of their lives.

The holistic philosophy is also applied to animal care, using natural remedies such as apple cider vinegar and garlic to prevent illness, eliminating the need for manufactured chemicals. Most of the income comes from pasture-raised lamb, chicken and beef alongside homemade items including honey garlic ferment, seasonal chutneys and beef tallow soap.

Research by the University of Huddersfield and the Halal Monitoring Committee (HMC) found that the halal meat and poultry sector represents around 15% of the total UK market, worth approximately £1.7bn annually and projected to grow to £2bn by 2028.

Lamia directs the family’s dog, Pip, to round up the herd of sheep, 10 of which are for qurbani. “The abattoirs like to front-load everything on the first day, so to avoid that chaos I like to pick the third day of Eid to book the slaughtering,” says Khalil, who helps manage the farm and also works as a butcher.

Khalil explains the importance of maintaining the niyyah (intention) for qurbani throughout the process. “The intention starts with the customers first. We take that intention on and select the 10 for qurbani, they get sent to the abattoir, then we pick it up and bring it back to the farm, butcher it, pack it and send it out as soon as possible,” he says.

“Customers don’t need to hold the knife at the time of slaughtering, they don’t need to be on site,” Khalil adds. “Our halal standards and what we are doing here is entirely based on trust. We want to establish that connection between the consumer and the farm.”

The farm does not hold a HMC or Halal Food Authority (HFA) certificate because they believe that true ethical practices should go beyond solely meeting the minimum requirements and that consumers should be more discerning and question the intentions behind certifications.

“A lot of people ask why we don’t have the stamp. They ask ‘How are you halal if you’re not certified?’ But we do everything by the halal standards,” says Lamia. “The meaning behind HMC and HFA, people are assuming a lot more than what it actually means. They look only at the point of slaughter.”

Caring for animals in smaller numbers is a key part of Willowbrook’s ethos. “We do things on a small scale, which ties into the importance of our responsibility on earth and making sure we are doing what it states in the Qur’an: tayib,” says Lamia. “We are not focused on just the slaughter, but the whole lifestyle.”

For the past 10 years, the family has observed a noticeable shift in how some Muslims approach qurbani — opting out of animal sacrifice and embracing lifestyle changes.

“We have a lot of vegans now and awareness of environmental issues and animal welfare especially in the Muslim community,” says Lamia, as she watches twin goats Ronnie and Reggie — jokingly named after the east London gangsters — tussle with each other in their pen. “The slaughter is a sunnah, not obligatory. If you think back to the time of the Prophet, it would not have been on this mass scale, they would have given to local charities and people they know who need it, and we have become connected to that.”

Everything on the farm is rooted in Islamic principles, guiding both intention and action. For Khalil, it’s not just about what they do, but how and why they do it. He reflects on the hadith where Anas ibn Malik reported that the messenger of Allah (peace and blessings be upon him) said: “Even if the Day of Judgment is upon one of you and he has a seed in his hand, let him plant it.”

“That encapsulates it perfectly,” Khalil says. “On the Day of Judgment, if you have a seed in your hand, you plant it. It doesn’t matter if your action has no result. You still do it because it’s right.”

After more than two decades of nurturing the land, Lutfi is preparing to pass the torch to the next generation — not just handing over a business, but a deeply rooted desire to reconnect sustainable farming and faith.

“Behind everything we do is this concept of khilafa — stewardship — which is mentioned in the Qur’an. We are placed as God’s stewards on Earth,” he says. “The idea that we are responsible for what we do, not just for human interaction but the environment, and ensuring we look after what’s around us. We can see the modern world isn’t doing that.”

Newsletter

Newsletter