‘We just don’t talk about miscarriage’

Asiya Dawood is determined that women should not have to face the pain of baby loss alone

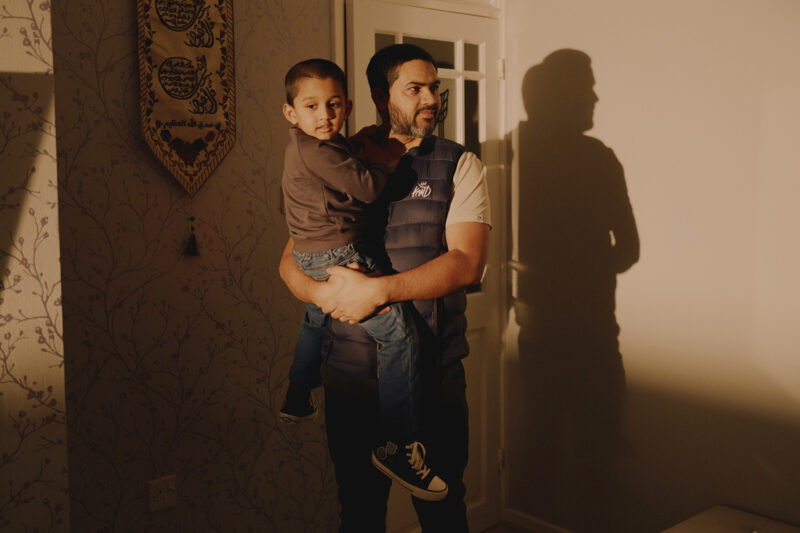

Asiya Dawood married her husband in 2007. It was 12 years before the couple welcomed their first child — yet Dawood says that she became a mother just a year after her wedding. Her first pregnancy, which ended at 18 weeks, was the first of four miscarriages and late-stage losses. It also marked the start of a long journey confronting both her ability to have children and her own culture.

“I had another loss in 2009 at nine weeks and another at 23 weeks in 2016,” she says. “I had to fight so hard to find what the cause was. I had to wait until I’d had three miscarriages until doctors would investigate. It’s such a traumatic thing to put people through.”

Medical guidance has since changed and now ensures that women who experience the loss of a pregnancy after 12 weeks are immediately entitled to tests and investigations. Dawood, however, had to put in months of research to understand what was happening to her. It took years for the cause of her miscarriages — an incompetent cervix, a genetic condition in which the pelvic floor cannot sustain the weight of a growing child — to be revealed and treated.

That experience led Dawood to set up the Asian Miscarriage Hub in 2022. The grassroots online support group has already provided help to hundreds of women and their families. She is also the face of the Sands baby loss charity for Black British and South Asian women and a regular public speaker on miscarriage.

“Miscarriage is a taboo topic. We just don’t talk about it,” Dawood says of attitudes widespread within South Asian culture. “I started my community to give hope to couples who had experienced losses, to show that if we can go through so many and then have a healthy baby, you can too.”

Approximately one in four pregnancies ends in miscarriage; a total of around 250,000 per year in the UK, according to government estimates. About 80% occur in the first trimester, before 12 weeks, and early pregnancy loss accounts for more than 50,000 UK hospital admissions each year. Losing three consecutive pregnancies, known as recurrent miscarriage, affects around one in every 100 women. The rates of recurrent miscarriage are similar in women of Asian heritage to those from white British backgrounds.

While miscarriage is a common experience, Dawood recalls that the initial expectation within her family and wider community was that she should deal with it in silence. “I was told, ‘It’s OK. You’ll get over it and you’ll get pregnant eventually, but we mustn’t tell anyone,’” she says. “I just went with the flow, but then you get all these questions, ‘What’s happening? You’ve been married for 10 years now, why aren’t you pregnant?’ ‘You have to see a doctor.’

“I would think, ‘I have been pregnant and I have had a baby. It’s just that the baby is not here.’ If you do not have that living baby with you, you are not classed as a mother, but I gave birth to a 23-week-old and he was my son.”

When Dawood talked to her family about her first loss, her mother revealed that she had lost two pregnancies as a younger woman. “It took her 25 years to open up. None of us knew. I think it’s sad that she had to carry that with her for so long,” Dawood says.

Determined that no one else should have to go through the pain of miscarriage alone, Dawood began to share her story on social media. Now, the Asian Miscarriage Hub offers a multi-platform support network on Instagram and Facebook. Dawood also hosts Zoom meet-ups and provides online coaching to support members. The stories shared within the group have given her the confidence to speak up on behalf of them all.

“I don’t hide the fact that I’m a Muslim because it’s important to point out that even if you do have faith, you are still allowed to grieve,” she says.

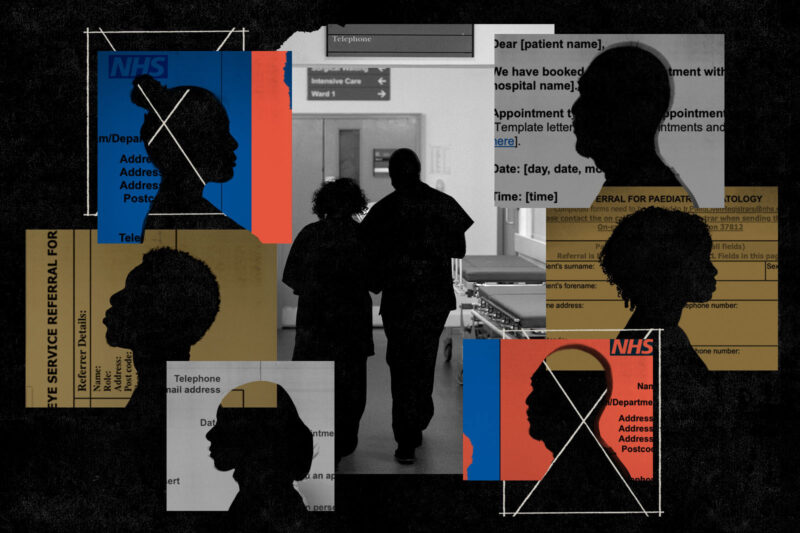

A 2021 study published in the medical journal BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth found that social stigma makes women from minority ethnic groups less likely to report miscarriages to healthcare professionals.

“As midwives, we are working to gently disrupt that silence by offering culturally safe, faith-sensitive care that allows women to grieve on their own terms, while also encouraging early access to support, treatment and understanding that loss is, sadly, a common part of many pregnancy journeys,” says Nafiza Anwar, a representative for the Association of South Asian Midwives.

According to Amina Hatia, co-midwifery manager at the baby loss charity Tommy’s, family and friends may not know how to handle or respond to the news that a pregnancy has ended. “How you give condolences when a bereavement has taken place often doesn’t feel right when a miscarriage has happened,” she says.

The result, she warns, is that women can end up minimising their experiences, rather than dealing with their grief, which can have adverse effects on both physical and mental health. Global studies indicate that up to half of women experience anxiety after miscarriage and 10-15% develop depression, which can in turn have adverse effects of subsequent pregnancies.

A lack of culturally appropriate care within the NHS means that Muslim women may also find the healthcare system more difficult to navigate. That could be because of the practical issues of trying to discuss their needs with medical staff when using English as a second language, the responses they might encounter as a result of their choices, or the way they speak about their faith in a medical setting.

“I have found in the past, with my own care, that using words like ‘inshallah’ got me looks from the midwives. A lot of women have told me that there have been misunderstandings due to the lack of communication and understanding between the midwife and patient due to these cultural differences,” says Dawood.

While many Muslim women find their faith a source of great comfort following the loss of a child she adds that, for some, religious belief can contribute to anxieties about speaking openly and frankly.

“You trust so much in the Almighty at that time and when it’s snatched away from you, you do find that trust is broken,” Dawood says. “It’s very easy for people to just say, ‘Have faith and you’ll get pregnant.’ You’re trying to build that trust up again, but it doesn’t happen overnight and it’s not easy.”

Although Dawood’s family have been supportive of her efforts to break the stigma surrounding miscarriage, some members of her wider community have struggled to accept her media appearances and public-facing role. She, however, recognises that her goal is to normalise such difficult conversations and that any resistance she encounters is part of the job.

“My main aim is to help women be bold enough to speak about their losses, to be brave enough to speak out to the community, to speak about their babies, and to be beautiful in embracing their story,” she says.

For more information, follow Asian Miscarriage Hub on Instagram and Facebook. Contact Sands and Tommy’s via their websites.

Newsletter

Newsletter