Three generations, one home: the changing face of an east London housing estate

The Ahmed family were among the first Bangladeshi Muslims to arrive at Will Crooks estate in Tower Hamlets. In the 40 years since they have seen their neighbourhood transformed

Tucked a few minutes’ walk behind the bustling Poplar High Street in Tower Hamlets, the Will Crooks estate appears as a time capsule of east London history. Four yellow and red brick buildings, built in the 1930s with the aim of housing working-class families, now sit in the shadow of the towering wealth of Canary Wharf.

By the turn of the 21st century, the estate had become home to successive immigrant communities: from Ireland, the Caribbean, and later Bangladesh.

Among the first Bangladeshi Muslims to arrive here were Azam and Hafsa Ahmed*, who moved into a two-bedroom flat in the council estate’s Leyland House with their six-year-old daughter Sabina in 1983.

Azam, now 87, found work in a nearby factory, while his wife Hafsa found comfort in the company of her sister, who already lived in a neighbouring building. Over the next decade, dozens of Bangladeshi families followed suit, turning Will Crooks into a hub for the Sylheti diaspora.

“On Will Crooks, everybody got along. Everyone would go out together, all of our neighbours were our friends,” Hafsa, 70, recalls of those early years on the estate.

In the 42 years since the Ahmeds’ arrival, they have seen and felt the effects of a borough gutted by the loss of social housing and increasing deprivation, and a community changed by soaring rents and house prices. Within those same walls they have brought up their four children — Sabina, 49, Jamila, 37, Shuhel, 35, and Samira, 30. The eldest three now have children of their own, each generation having lived together in the flat at some point.

Bangladeshi migrants, mostly from Sylhet, first began to arrive in significant numbers to Tower Hamlets in the 1970s, primarily driven by economic hardship and the hope of better work opportunities in the UK. Today, Bengalis make up 35% of the population in the borough — the highest concentration of Bengali people outside of Bangladesh.

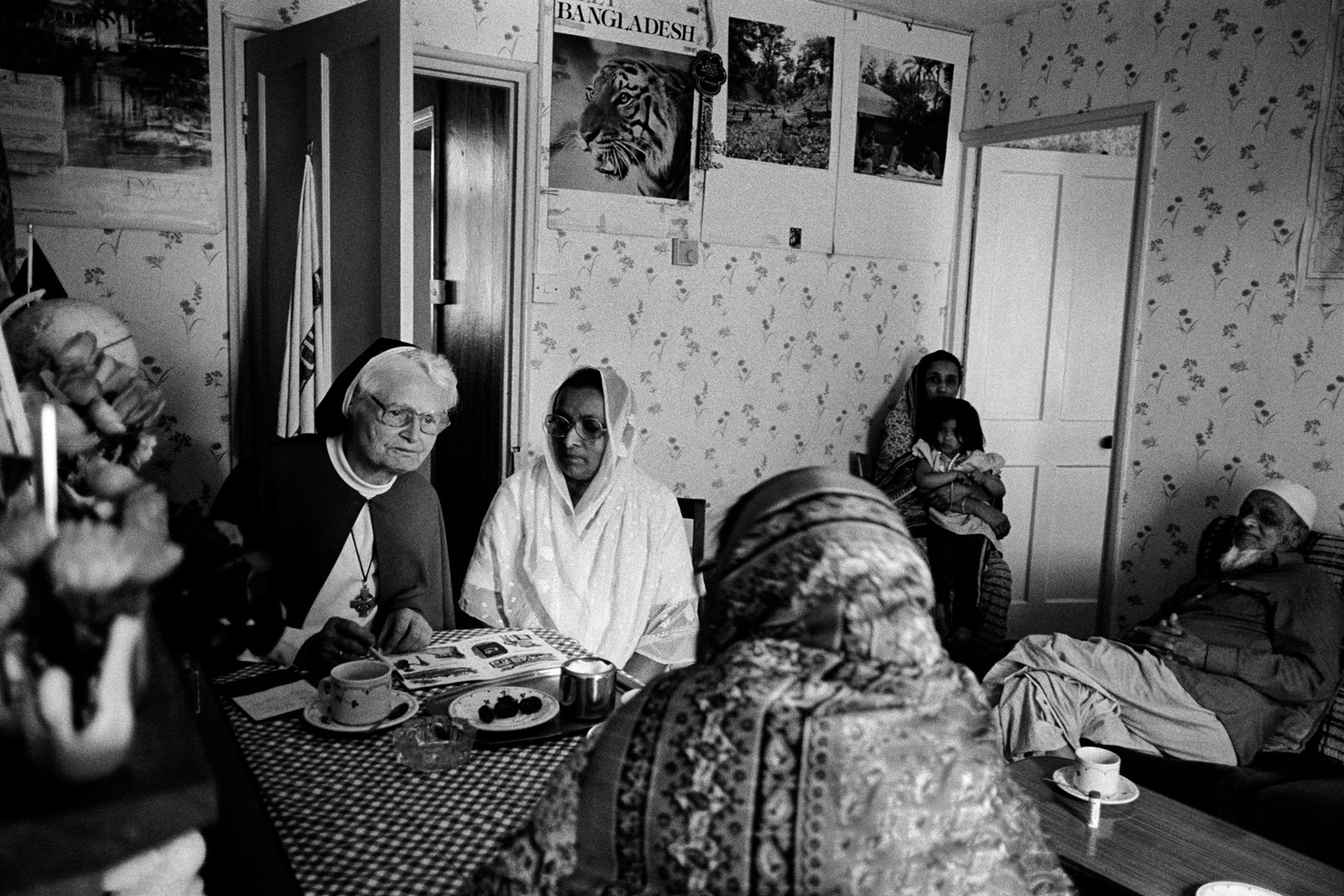

Sister Christine Frost, a community activist who helps run the St Matthias Community Centre in Poplar, has lived on the estate for more than 50 years. She says the first Bengali families settled in Will Crooks reluctantly after being assigned homes by the council, with some telling her they would have preferred to live in Brick Lane, where there was already an established community.

“I always felt they were helicoptered in. The early families had no money, they had an awful time,” Frost says. “There was nobody to tell them about the cultural changes here. I remember the mums — no one had a buggy, they carried the babies everywhere.”

Yet it soon became clear that these new families had formed connections with one another. Many came from the same part of Bangladesh and had escaped poverty in their rural hometowns.

Sabina recalls her family quickly establishing themselves with their Bengali neighbours. “I remember going to visit other people’s homes with my mum, and getting the bus and going shopping in groups with our neighbours,” she says.

The local council soon began making efforts to support integration. In primary schools, some teachers learned Sylheti so they could communicate with the children, while Bengali women with English skills worked as teaching assistants.

But their lives were marred by racial tensions. Hafsa recalls being verbally abused when she left the estate to buy groceries, or incidents when young white men came into Will Crooks with baseball bats and smashed people’s cars.

Dr Aminul Hoque, a researcher at Goldsmiths, University of London, with a special focus on British Bangladeshis, recalls his own encounters with violence “every single day” as a child in Tower Hamlets.

“Being spat at, excrement shoved through the letter box, being called all sorts of horrible racist words, dogs being set on you, and feeling like an outsider in the school playground. This was the reality of the 1970s, 1980s east end of London, where racial violence towards Bangladeshi communities was an everyday experience,” he says. The far-right National Front political party’s headquarters were in nearby Hackney between 1978 and 1980.

At that time, anti-migrant and racist movements were fired up by tensions over housing, with established white communities perceiving newly arrived Bangladeshi families as a threat to their position on council housing waiting lists.

In 1993, Derek Beackon, in nearby Millwall, became the far-right British National party’s first elected local councillor. “He was elected mostly on anger around housing going to the Bengali community,” says Frost. “His election had a lot of impact. Around here you saw the St George’s flag come up.”

A prominent community activist, Frost spearheaded early efforts in strengthening ties between new families and existing residents in Will Crooks. When the Ahmeds first arrived, Frost would go over to their flat to give them English lessons.

“From the word go, I realised that we are one community, one family. I thought, if we don’t come together now, we will be killing each other in a few years time,” says Frost.

Today, Bangladeshis are the second-largest demographic in the area after the white community and play a central role in civic engagement, serving as elected councillors and MPs. Still, housing continues to be a source of tension within the borough. In 2023, Somali families accused the council of removing them from waiting lists or allocating them unsafe and unfit homes due to their race.

The Ahmeds’ home sits up six flights of stairs on the third floor of the block, overlooking a communal playground at the front of the building and a residents’ gardening plot to the rear. Plastic boxes full of personal belongings are piled high outside their front door — signs of a growing family confined to a limited space.

Hafsa and Azam’s is just one of more than 23,000 households on the Tower Hamlets housing waiting list, the fourth-longest for any London borough. The couple have been on the list for more than 16 years, and are hopeful they might secure a more suitable home soon, with around 100 households ahead of them.

With the fastest-growing population of any local authority across England and Wales — increasing by 22% between 2011 and 2021 — approximately 16% of households in Tower Hamlets are living in properties that are too small. Data obtained by Hyphen through Freedom of Information (FoI) requests suggests that more than half of English councils did not approve the construction of any new social rent homes during Labour’s first six months in government. In Tower Hamlets, the council granted permission for 594 new homes, of which 56 were earmarked for social rent.

A spokesperson for Tower Hamlets told Hyphen overcrowding is “a serious problem due to a chronic lack of genuinely affordable homes”. They said the council aims to deliver 4,000 new social rented properties “with a focus on family-sized homes”, and have introduced a scheme to buy back former council homes sold under Margaret Thatcher’s right-to-buy policy since it was introduced in the 80s.

While both daughters Jamila and Sabina have moved out of the family home — Sabina into a property one floor below her parents — the flat is still too small for the Ahmeds and their remaining children. Shuhel, who is divorced, has three young children who often stay over. When they visit, all of them sleep with him in his bedroom.

The living room is bright and airy with a sofa and an armchair arranged around a matching cream rug. A freezer stands at one end of the room. In another corner, there is a pile of neatly folded mattresses and duvets.

Jamila tells me this is where her parents sleep, rolling out their bedding every night and packing it away again in the morning. “They both have back problems, so they find it difficult to get up and go to the loo,” she says. “And there’s always draughts coming in, which they feel more because they are on the floor.”

Jamila remembers struggling to find a place to study as a child and not being able to invite friends and family over. “But it was also normal to us,” she says. “When you’ve never had the space, you don’t really know what you’re missing out on.”

The family has been offered split-level maisonettes over the years, but they haven’t been suitable for Azam and Hafsa’s age and physical health needs. None of the buildings on the Will Crooks estate have lifts and the stairs are becoming unmanageable for the elderly couple.

“My mum’s got arthritis in her knees, so she’s essentially housebound and can’t go out,” Jamila says.

When Hafsa does venture outside for doctor’s appointments, the family has to help her come back up to the third floor. “But then that’s it, she is in pain for the rest of the day,” Jamila adds.

Azam, a passionate gardener, still tends to the small plot behind the building, but each trip is difficult for him. “Both of my knees aren’t very good and I also struggle with my breathing. If I go out, I have to stop at every floor to catch my breath when coming back up,” he says.

Azam has even stopped going to the local mosque. “The mosque was his community, it’s where his friends were, where he would go to have a chat with people,” Jamila says.

Many former residents of the estate took advantage of right to buy, allowing social housing tenants to own their council homes at a discount to the market price. While some profited by selling and relocating to larger homes in suburbs such as Barking and Redbridge, the loss of former council homes to the private market drove up rents. On Will Crooks, a one-bedroom council flat that used to cost £600 a month is now privately rented for upwards of £1,500 per month.

Frost also blames the government-founded London Docklands Development Corporation (LDCC) for driving inequality in the area. The organisation, founded in 1981, was tasked with regenerating the Docklands area of east London. As luxury skyscrapers went up in Canary Wharf, the LDDC promised that prosperity would “trickle down” to the surrounding areas.

But Frost says that, in reality, the outcome was entirely different. According to the 2021 census, around 67% of households in Poplar are deprived in at least one of four indicators: employment, education, health and overcrowding. In Canary Wharf, that number falls to 36%.

“In the process of building the Docklands Light Railway and the Limehouse Link, we lost 500 council homes,” Frost says, adding that it’s as if there’s “a barricade” around Canary Wharf dividing these communities — even though they are separated by little more than a road.

Today, Jamila and Sabina say more than two-thirds of people they grew up with no longer live on the estate. Their departure has weakened the community they once had. “It’s hard to have a community when no one is here. It’s not as close-knit as it used to be,” Sabina says.

“In my time, we used to play outside, and because of that our mums used to go out and get to know the neighbours. No one’s doors were ever locked, they were always open and it was safe to do that.”

Hafsa and Azam have felt the disappearance of their neighbours the most. “Before they would be in and out of each of their friend’s flats, they would all be doing things together, but now they are lonely,” Jamila says.

Still, the Ahmeds are resolute that they will not leave Tower Hamlets.

“Our whole life is here,” Hafsa says. “It’s not just an area, it’s our community.”

*Names have been changed

Newsletter

Newsletter