I will always find my way home to my siblings in Gaza, no matter how long it takes

Palestinian playwright Ahmed Najar writes about maintaining his relationship with his brothers and sisters, despite living so far away

When I left Gaza two decades ago, I didn’t think I’d become a ghost in my own family — especially not to my 12 siblings. I knew I’d miss things, but I didn’t realise just how much: the weddings; the births of my nieces and nephews; the squabbles over who gets the last piece of kanafeh at family meals. I thought phone calls would be enough to keep me tethered to them. And, for a while, they were.

At first we spoke almost every other day. My siblings would take turns passing the phone around like a sacred object. One minute I’d be laughing with my younger sister Nour about the neighbour’s latest drama, the next I’d be teasing my elder brother Mohammed for still being afraid of lizards.

There was an intimacy to those calls, a warmth that made the distance feel bearable. I remember one night, my sister called me from hospital after giving birth to her first child, whispering into the phone so she wouldn’t wake the baby. “You’re the first one I called,” she said. I cried after we hung up. Not because I was sad, but because, in that moment, I didn’t feel so far away.

As children, my siblings and I were inseparable in that chaotic, loving, sometimes infuriating way. I remember one summer afternoon when I was about 10 years old in Gaza — the electricity had gone out, again, and we decided to make a game of it. We set up a makeshift tent on the roof with old bedsheets and told ghost stories until the sun set. Mohammed tried to scare us by pretending there was a djinn behind the water tank and Nour shrieked so loud the neighbours came to check in. We laughed until our stomachs hurt. That night, we fell asleep up there under the stars, wrapped in each other’s warmth, swatting mosquitoes as we whispered secrets.

That’s the version of us I carried with me when I left. But gradually, the image changed. The calls became less frequent. Our conversations shorter, the content more surface level. The closeness we once had had begun to fade, like a photograph left too long in the sun. We were running out of things to say — not because nothing was happening, but because our lives had quietly drifted apart and the distance kept growing. Our once solid common ground was crumbling.

When I left Gaza in 2003, I told myself I’d visit often. But Gaza doesn’t work like that. In 23 years, I’ve managed to visit three times, each year monitoring the news like a stockbroker watching the market, waiting for the slightest sign that the borders might open.

And when they finally did — usually for three days, announced with all the predictability of an earthquake — I would have to drop everything. I scrambled to book flights, begged for time off work, bought last-minute gifts and then took the 36-hour odyssey from Cairo through Egyptian checkpoints that are less about security and more about testing the limits of human patience.

The first two visits were short. Barely two weeks, just enough time to hug everyone. The conversations with my siblings felt rushed, like we were trying to pour years into a few fleeting hours. I’d sit there, watching them talk over each other, share memories I wasn’t part of, make plans I wouldn’t be around for — and I’d smile, but inside I felt like a guest. Not quite a stranger, but no longer one of them in the way I used to be.

It hurt in ways I hadn’t anticipated. I thought seeing them would fill the gap, but instead it made the distance feel even more real. They had built a shared present and I was still holding onto a shared past. I missed the way my siblings argued over who got the best seat on the couch, the way they barged into my room without knocking, how we’d fight and make up in the same breath.

Sometimes I felt like a traitor for leaving. Other times, I felt like a ghost helplessly watching their lives continue without me.

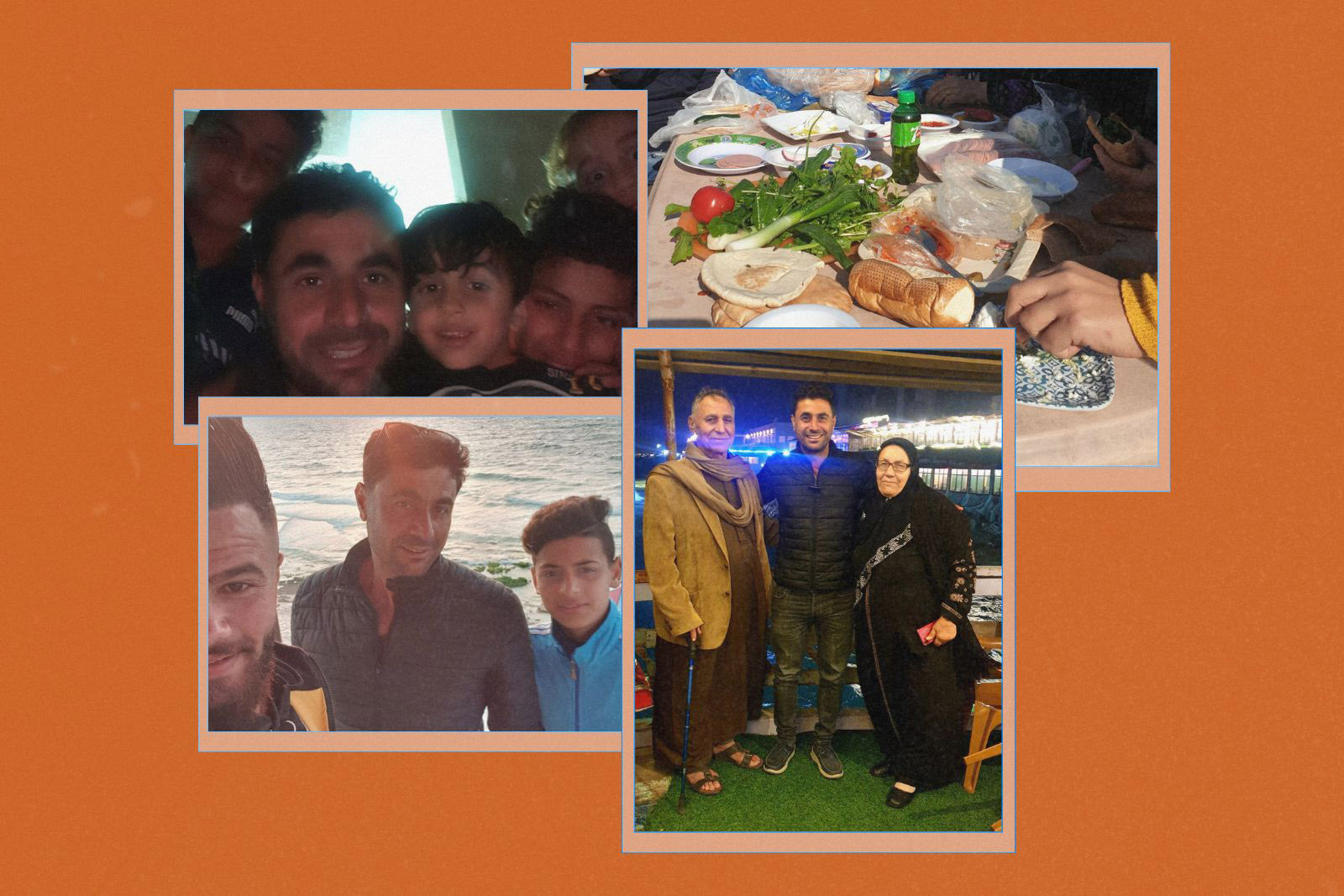

But in 2021, I was able to spend two full months in Gaza. That time, I didn’t just see my family — I felt them again. They took me to their favourite cafes, restaurants and spots by the beach. We picnicked by the sea and strolled along the shore, sipping fresh juice, gossiping about our other siblings. There was laughter over stories I hadn’t heard before and inside jokes I was finally able to understand. It felt like I was part of them again.

I learned things I never knew, like the fact that one of my brothers is allergic to apples. Apples, of all things. Another had quietly taken up woodworking, a skill I never knew he had. My sister had become the organiser of everything. I watched my younger brother, who used to follow me around like a shadow, now give advice to his own kids with the same phrases my father once used with us.

I felt proud of who they had become, but also quietly heartbroken that I hadn’t been there to witness the becoming.

Then, of course, I had to leave again. And leaving Gaza is just as unpredictable as entering it. The borders might open suddenly and there’s no time for proper goodbyes. Just grab your bags and hope you make it out.

The night before I left in 2021, we stayed up late, talking, laughing and delaying sleep because we knew that when morning came it would mean another long separation. My mother tried to act normal, but I could see the sadness in her eyes. My father, always the stoic one, gave me a long, silent hug. My siblings, my nephews and nieces all had their own way of saying goodbye. Some cracked jokes, some avoided eye contact, some just stood there, knowing that we didn’t need to say anything at all.

And then I was gone. Back to phone calls that sometimes lasted only five minutes. Back to watching from afar, feeling the distance settle in again.

But something was different this time. That visit had reminded me who I was — not just someone who had left, but someone who belonged.

I am a brother who can always find his way home, no matter how long it takes.

Newsletter

Newsletter