The Glassworker is a milestone for Pakistani cinema

Usman Riaz’s animated feature tells a story that resonates across borders, and reminds audiences of the radical act of making something beautiful

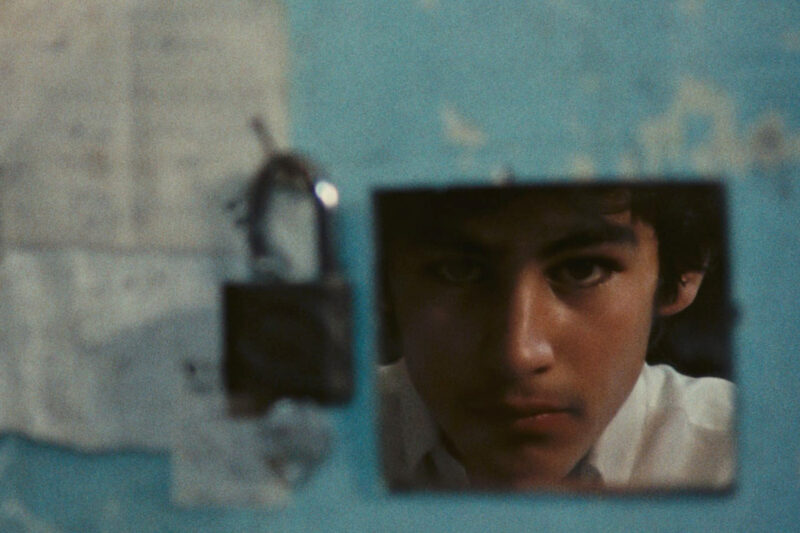

Usman Riaz’s The Glassworker is a meticulous work that marks not just a milestone for Pakistani cinema, but a reminder of the possibility of filmmaking magic when true ambition and fresh perspectives are present in the craft.

As the country’s first fully hand-drawn animated feature, The Glassworker is burdened with an enormous weight to prove the mettle of a potential new well of creativity. But to view it solely through the lens of its historical firsts and future potential would diminish its achievements as a piece of cinema.

This is a story about a legacy passed down from father to son, the bond between young artists, and the push and pull between maker and craft, all set against the steady erosion of a world sliding into authoritarianism. Riaz, as director, cinematographer, co-writer and co-composer, pours himself into every square millimetre of this piece, rooted in the tradition of the great animators while creating a narrative that is unmistakably his own.

Set in the fictional port town of Waterfront, we follow young Vincent, apprentice to his widowed father Tomas, in their glassblowing studio. Life shifts when Alliz, the daughter of an army colonel, arrives in town. As their bond deepens, both Vincent and Alliz must navigate a world shaped by the looming militarisation on its borders, where their artistic dreams and personal freedoms come under quiet threat.

Tomas resists the forces changing their town, clinging fiercely to the integrity of his work, while Alliz struggles to reconcile loyalty to her authoritarian father with her growing desire for a life defined by the wider possibilities of love.

Confident enough not to rely upon bombastic plot twists or shrill melodrama, The Glassworker has a gentle magical realism, rooted in the mythology of djinn fire spirits, but finds its true power when art, romance and politics intersect.

Where much contemporary mainstream animation hides behind the bland polish of digital production, Riaz’s film reclaims imperfection. He draws clear inspiration from the work of animator and Studio Ghibli founder Hayao Miyazaki, with every hand-painted detail an exquisite piece of art — the light sparkling across the shimmering sea, Vincent’s tears and Alliz’s violin. The craftsmanship extends to Riaz’s own rich musical score, performed by the City of Prague Philharmonic Orchestra. The music doesn’t merely accompany the story: they dance together.

In charting this path, Riaz joins a small but essential lineage of Muslim animation that refuses to flatten itself for the western lens. It’s impossible not to think of Persepolis, Marjane Satrapi’s masterpiece of Iranian girlhood and revolution. The Glassworker, while very much its own creation, carries that same vitality by telling a story that resonates across borders. It is a searing reminder that animation can be a medium for adult storytelling, not just childish escapism.

The emotional honesty of The Glassworker is all the more affecting for how gently it arrives, introducing us to the seaside town of Waterfront where the community lives a slow-paced but vibrant existence. We don’t commence with grand pronouncements about war or authoritarianism, instead, Riaz allows a slow, chilling realisation of how even the smallest dreams are under threat. The tension between creation and destruction plays out in quieter battles: a father’s resistance to change, a young girl’s struggle against a pre-written fate, an artist’s desperate attempt to keep beauty alive in a world that rewards obedience.

Yet for all its anti-war messaging and delicate melancholy, The Glassworker is an optimistic work. Even as brutal political ambition seeks to destroy them, Vincent and Alliz’s connection endures, fragile but as exquisite as the finest blown glass. Riaz walks a tightrope between the ignobility of war and the strength of the human spirit, showing that it is possible to confront tragedy without succumbing to despair.

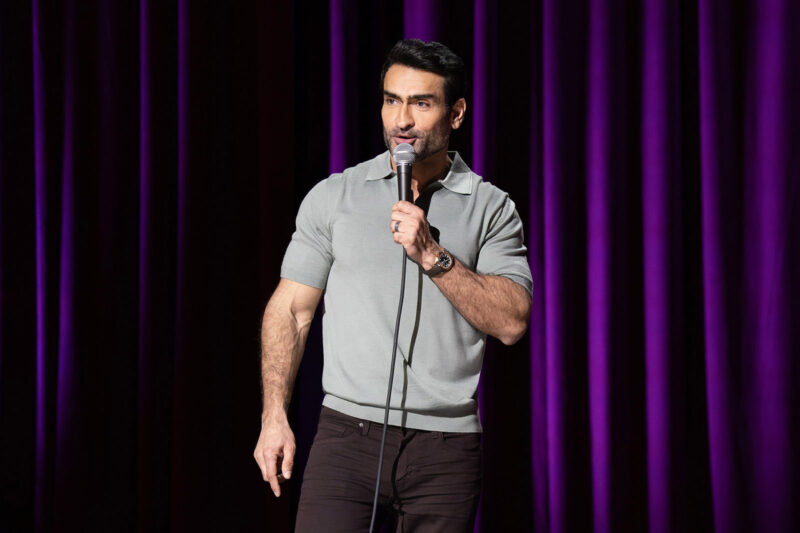

The voice cast, led by Art Malik, Sacha Dhawan and Anjli Mohindra, ground the story with subtle performances in a script where so many conversations are about what is being left unsaid. Their naturalism lends a complexity to a medium that too often leans on celebrities hamming it up to create soulless spectacle.

The film premiered at the Annecy international animation festival in 2024, the most prestigious event of its kind, and was met with rapturous acclaim as a breakthrough for South Asian animation. Now, it arrives in the UK as a centrepiece of the UK Asian film festival, offering British audiences the chance to experience Riaz’s hand-drawn world. Its global release speaks to a significant moment, not just for the film, but as proof of a wider interest in Pakistani animation.

Watching The Glassworker feels like being entrusted with Vincent’s exquisite creations — something precious, intricate and made with profound love. In a world often bent on destruction, Riaz reminds us of the radical act of making something beautiful.

The Glassworker is showing at the UK Asian film festival’s closing night on 10 May.

Newsletter

Newsletter