Artist Mahtab Hussain on turning the gaze back on the surveillance state

What Did You Want To See? celebrates British-Muslim identity while exploring the tension between being visible and being monitored

Mahtab Hussain always felt different when going to the mosque as a teenager. The artist’s bleached blond hair and piercings made him stand out and he didn’t feel he belonged. Those experiences growing up in Birmingham were uncomfortable at the time but, looking back, they shaped how he views community and representation today.

“It’s interesting to reflect on how those early feelings of alienation later influenced my work as an artist,” says Hussain, who is now based between Birmingham and West Sussex. “They pushed me to explore themes of visibility, identity and the complexities of belonging — both for myself and for the communities I connect with.”

Hussain’s practice investigates the relationship between displacement, representation and resilience. He explores those themes through in-depth research and has built a portfolio that challenges the prevailing concepts of multiculturalism. His solo exhibition What Did You Want To See? was commissioned by Photoworks and is now showing at the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham’s leading contemporary art space.

It’s a clear departure from Hussain’s usual portrait photography, employing multimedia such as film, painting and installation, each element offering a distinct way of engaging with the viewer. The result is both a galvanising call to action and a quiet invitation to experience Muslim identity in a “more reflective way”.

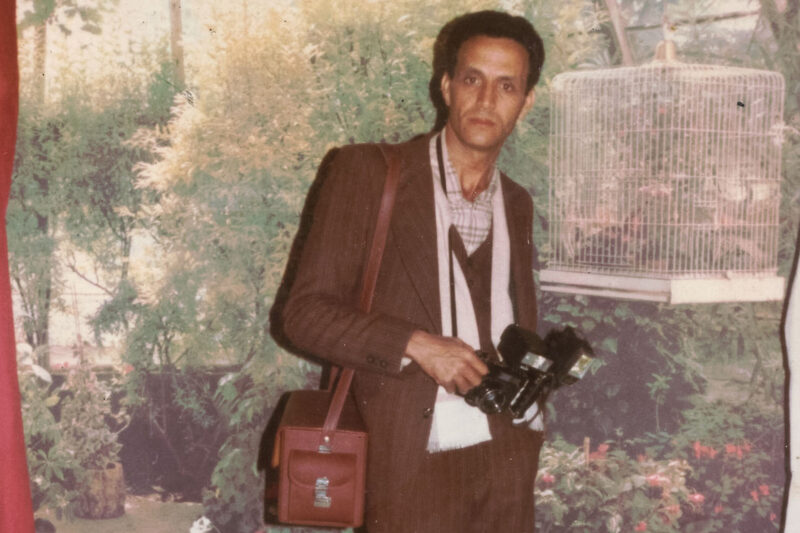

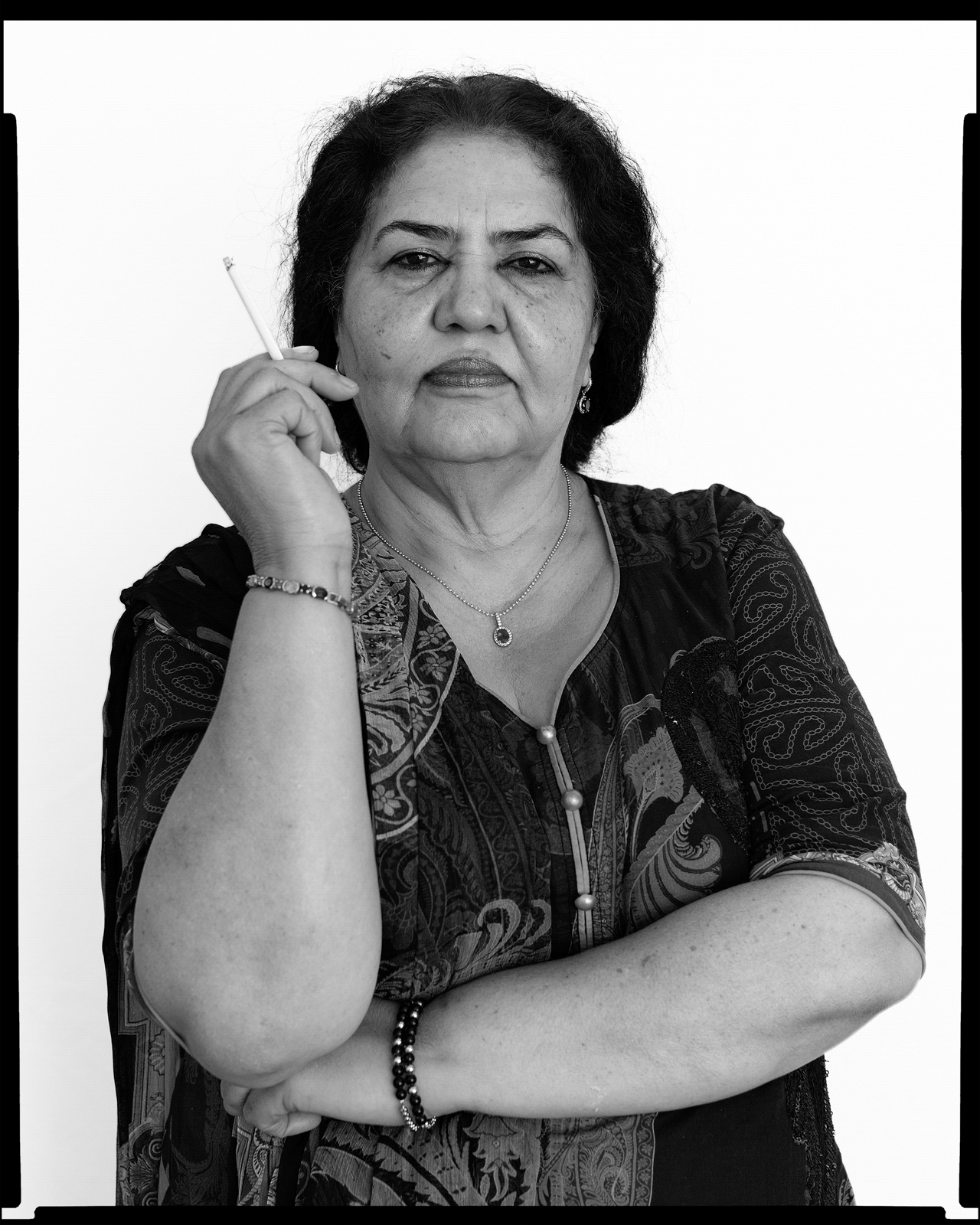

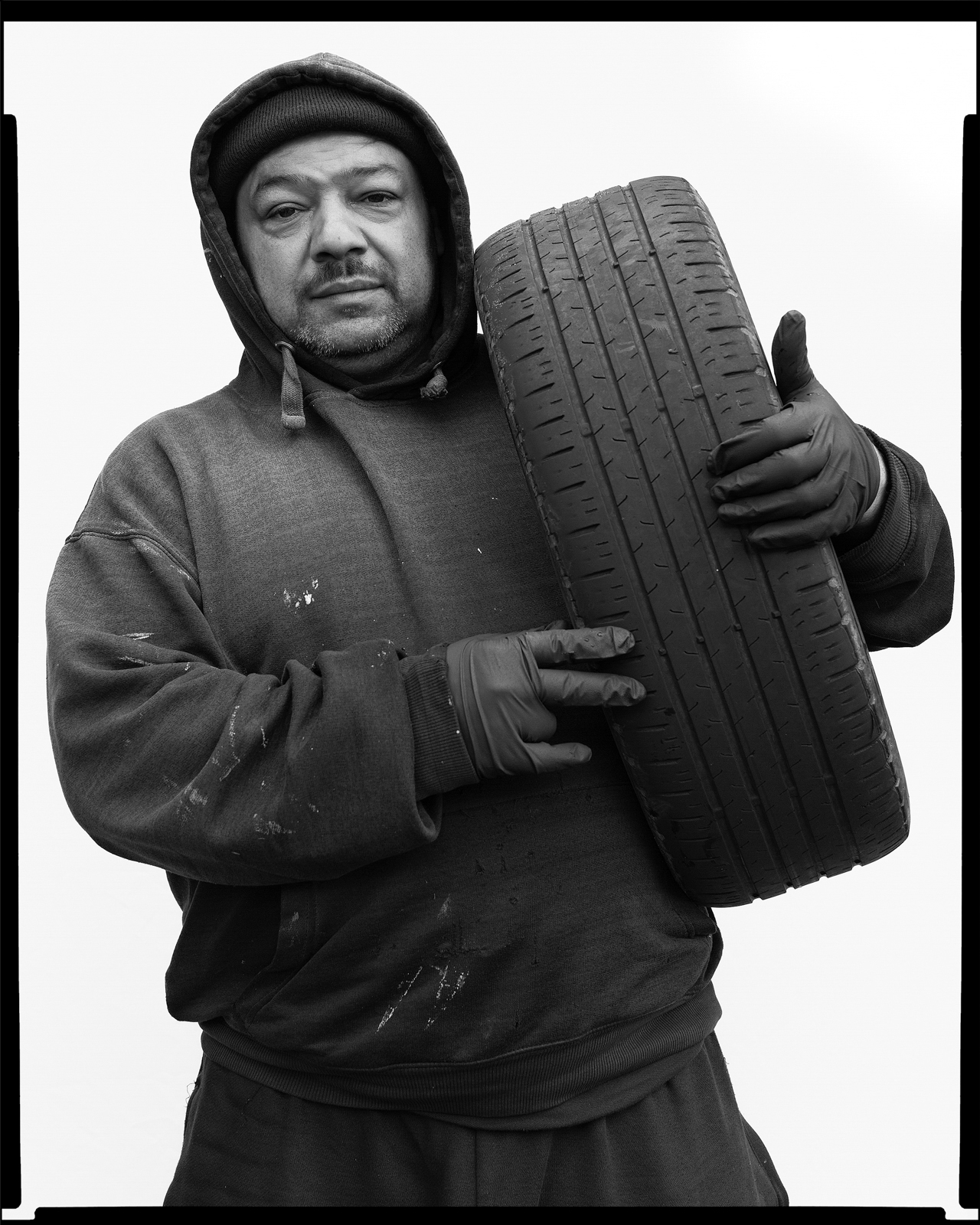

One portrait series in the show offers a personal and singular study of Hussain’s community in Birmingham. His subjects range from close family members — his mother is the “badass woman” smoking a cigarette in one arresting image — to community members such as Shaf, who has a tyre shop that Hussain used to drop into regularly.

“I did my usual thing, stopping people in the street and going into community centres,” says Hussain. “But I also went back to people that I’ve met over the years and who I’ve photographed before but perhaps not shown before, whose story I want to share.”

The photographs are influenced by Richard Avedon’s American West series, in which the renowned portrait and fashion photographer travelled the country between 1979 to 1985, conducting more than 700 sittings with an 8×10 Deardorff large-format film camera. “I wanted to go back to the simplicity and the range of black and white portraits,” says Hussain.

“I don’t think there’s been a series created like that relating to the Muslim South Asian experience. I wanted to have that conversation in my work and celebrate the individual,” he says. Although Hussain wants to keep the camera he used a secret, the effect is as cinematic and atmospheric as the Deardorff. By portraying South Asian Muslims in this way, Hussain gives the same gravitas to his subjects as Avedon did in his seminal work.

While the black and white portraits are a celebration of identity, the exhibition also interrogates a darker side of British Muslim experience — the UK’s surveillance culture, which disproportionately targets Muslims through programmes such as the government’s Prevent strategy. “Muslims are often framed and observed through a lens of suspicion and misrepresentation,” says Hussain.

That is something he says has experienced first-hand, recalling the time he was stopped under Section 44 at London’s Charing Cross train station, which allows for officers to search for identity and nationality documents without a warrant, and the many hours he has been detained at UK border control. “It becomes normal, like breathing air. This is the reality for many people within my community, where discrimination is woven into everyday experiences. It’s our lived realities,” he says.

This idea is particularly potent in one installation created in response to Birmingham Council’s Project Champion, which installed more than 200 surveillance cameras in the city’s majority-Muslim areas in 2010. They were removed a year later, leaving patches of discoloured asphalt on the pavements, which Hussain has repurposed throughout the gallery. By inserting them into the show, he critiques the council’s intentions: “What was it that you wanted to see when you looked at us as a community? What did you think of us, and why did you feel entitled to exert such power over us?”

Hussain explores those questions further in his documentation of 160 Birmingham mosques, which he captured during the summers of 2023 and 2024. The series reveals the diversity of mosque architecture — from gleaming golden domes to nondescript buildings hidden behind metal gates — but also speaks to the pervasive nature of data collection and classification, photographed in a way to imitate the cold distance of a CCTV camera.

“Through my practice, I attempt to turn the gaze back on to the observer,” says Hussain. “Questioning what it means to be watched, to be surveilled and how this shapes the narratives of a community.”

Hussain’s early life in Birmingham — one of the UK’s “super-diverse” cities — was affected by experiences of racism, particularly while living in the majority-white area of Druids Heath following his parents’ divorce.

“For 10 years, I was cut off from the Muslim community, disconnected from my culture and heritage,” he says. “The only connection was food shopping at the weekends and eating samosa and kutlumas wrapped in brown paper bags with my brother.”

His practice has allowed him to reconcile those years, as we see in the film Here is the Brick, created for the exhibition in collaboration with the playwright and novelist Guy Gunaratne.

Hussain challenges viewers to witness both the pain and joy of growing up Muslim in Britain through a kaleidoscope of clips from across television, films, newscasts, sporting events and internet videos. “We spent hours online, sifting through various pieces of media, desperately searching for fragments that would trigger the raw emotions and memories we needed to process,” he says. “We had to go through a purging process, extracting moments that had deeply scarred and shaped us. I vividly remember the intense, physical experience of working on this film.”

Despite Hussain’s ability to reclaim difficult parts of British history through his art, he feels the wider conversation around multiculturalism here is increasingly fractured: “While there are still pockets of solidarity and community, there’s a growing sense of division, heightened by political rhetoric and policies that seem intent on creating an ‘us versus them’ narrative.”

But Hussain hopes that his work and other art forms can at least create space for reflection and questioning. “Art allows us to address complex issues in ways that words alone often can’t,” he adds. “Through visual language, art can bypass cognitive defences, allowing people to engage with difficult or uncomfortable topics on a more visceral level.”

Mahtab Hussain’s What Did You Want To See?, commissioned by Photoworks, is showing at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham until 1 June.

Newsletter

Newsletter