A Bulgarian artist’s journey to unearth her family’s forbidden Muslim name

Vera Hadzhiyska’s multimedia project recovers names that were erased in Bulgaria’s forced assimilation campaigns of the 20th century

In Whisper, a sound installation created by Bulgarian artist and photographer Vera Hadzhiyska, four speakers are positioned on a series of plinths, each covered by a traditional headscarf. The names of Bulgarian Muslims — erased after a series of forced assimilation campaigns in the 20th century, in which the community was made to adopt Slavic names — are whispered by members of Hadzhiyska’s family. The first two plinths stand tall. The others are low to the ground, the headscarves lying crumpled in a pile.

The concept is to evoke a simultaneous feeling of celebration and exclusion: how the headscarf was denied to Bulgarian Muslims, while included as part of Bulgarian folk dress. It is a reclamation “to bring back into public space the names that were forbidden”, Hadzhiyska says.

Whisper is part of With the Name of a Flower, a multimedia project now on display in a group exhibition at the National Gallery of Kosovo. Hadzhiyska, based in London, combines photography, video and sound, drawing on archival research and interviews. Her family was made to change their names in 1972, and Hadzhiyska’s goal has been to unearth this history of state repression.

“As a descendant, it was partly my responsibility to share the stories and lived experiences of my family and the countless people from the Muslim community who went through name changes and repression,” she says. “I don’t want their experiences to be forgotten.”

Hadzhiyska’s parents were not religious when she was growing up, yet the family gathered to celebrate national Bulgarian Orthodox holidays. They also congregated at the home of her maternal grandparents during Ramadan, which, as a child, she assumed was just another family gathering. It was only in 2017 when Hadzhiyska was beginning research for a master’s degree in photography at the University of Portsmouth that she began turning to her family history.

In one conversation with her grandparents about their past, they matter-of-factly referred to their old names. When Hadzhyska asked her parents why she and her brother were never told about this aspect of the family’s background, they said that they had never hidden it intentionally. But she sensed discomfort.

“This is very difficult for them, because of the way they were told to assimilate and erase that part of their identity,” she explains. “They wouldn’t have mentioned it at work. It makes sense, because of the circumstances.” For Pomaks — a term used to describe Muslims of ethnic Bulgarian origin — concealing Muslimness was a way to evade discrimination and ridicule.

Hadzhyska’s grandparents initially responded to her questions with silence, which has slowly dissipated in the years since she began the project. “The fear instilled in them at the time of the name-changing campaigns was still present,” she says.

State-enforced assimilation reached an apogee in the mid-1980s with the Todor Zhivkov regime’s “Revival Process”, forcing more than 350,000 Bulgarians of Turkish origin to leave the country. Under Zhivkov, who ruled Bulgaria for 35 years, these communities were forced to change their names and risked death and unlawful detention at the hands of the state.

Yet this subjugation predates the Revival Process, beginning in the early 20th century. Over eight decades, both Pomaks and Turks were the target of several campaigns. These involved the renaming of more than 200,000 Pomaks, the conversion of mosques into churches, a passport name-changing campaign in the 1950s, the migration of 130,000 ethnic Turks in 1969, and the banning of religious clothing in the early 1970s. The effects were far-reaching enough to encompass the change of ancestors’ names on fading tomb inscriptions.

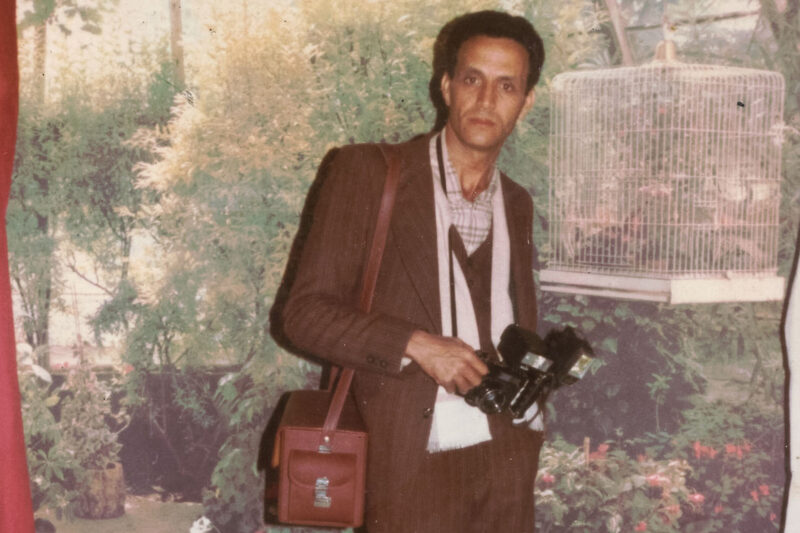

Hadzhiyska found documents related to her family’s own name change in the state archives of Smolyan, a region densely populated by Muslims where her grandparents’village was situated. She came across the form her maternal grandfather completed for his wife and children. “I was imagining him filling it out, holding that same piece of paper. It was surreal,” she says.

She began her artistic project through a series of self-portraits. “The self-portraiture was a way of working through that experience and navigating that shifting sense of identity and belonging,” Hadzhiyska says, referring to her shock upon finding out about her heritage.

Several images are taken among the interiors of her paternal grandparents’ Soviet-style apartment, on a couch covered in an orange mohair throw. In some, Hadzhiyska wears a yellow dress that belonged to her namesake — her paternal grandmother Vera, who was once known as Ferde.

With the fall of the Communist regime in 1989, Bulgarian Muslims were allowed to use their Muslim names once again. Some returned to their old names, while others, like Hadzhiyska’s family, retained those they had taken on. In 2012, the Bulgarian parliament adopted a resolution condemning the Revival Process, describing it as an ethnic cleansing campaign.

Though the history of this repression is more widely known now, when Hadzhiyska was at school, she says the curriculum often omitted mention of the atrocities committed during the Soviet era towards Bulgarian Muslims as well as other marginalised communities, while vilifying Turks — and Pomak Muslims by extension — as part of discussions about the 500-year-long Ottoman rule over Bulgaria.

“The influence of these tales was widespread, despite not being entirely historically accurate, and they became ingrained in people’s consciousness,” she says. “In all of them, the Ottomans, Turks, and Muslims were presented as the villains. I never associated my family with these representations, but I realised other people must have.”

Her own research has also reframed her relationship with the nature of national history itself. “What is in the official books — is that the truth, or is there something that has been erased for this to be the prevailing narrative?” she asks.

In one of Hadzhiyska’s short films, shot at a mosque in Devin in 2021, she turns her camera towards the recollections of older members of the community. These men and women remain faceless, denoted only with the initial of a first name in the translated subtitles. They, like her grandparents, experienced the violence of forced assimilation firsthand. “We went through so much anguish,” an elderly man named R tells Hadzhiyska. “We survived everything.”

Vera Hadzhiyska’s publication With the Name of a Flower is out now, and the multimedia project is on display at the National Gallery of Kosovo. She has also co-curated an exhibition Rethinking Eastern Europe which is showing at Copeland Park, London until Sunday 16 March.

Newsletter

Newsletter