The Ramadan that changed me: three comedians on a transformative moment

How an experience during the holy month shaped the lives of Ola Labib, Bilal Zafar and Shazia Mirza

Ola Labib — ‘Do you know how hard it is to be nice to a heckler?’

My first comedy gig during Ramadan was unforgettable — and the ultimate test of patience.

It was at the beginning of my career about seven years ago. A free entry, open mic gig in Liverpool town centre, with a stag do. That combination equals one of the rowdiest crowds I’ve ever performed to.

I knew it was going to be a long night. At the time, I was working as a clinical pharmacist in an oncology unit, so when I arrived I was physically and emotionally drained, running on an empty stomach. But, in those early days, I went into every gig thinking: “This one’s going to be my big break.” I trudged into the green room, clutching my pre-packed iftar, containing one courgette mahshi and two samosas, like a prized possession.

You’d think having pre-warned the promoter that it was Ramadan that they’d accommodate a five-minute do not disturb period where I could eat and pray. Nope. One of the comedians hovered over me like a possessed seagull the second my container lid came off. “Oh, that smells amazing! What is it?” he asked. But before I had a chance to answer: “You mind if I try a bit?” I nodded reluctantly and, to my horror, he picked up the courgette mahshi — the MAIN part of my meal — and shoved it in his gullet. And to make things worse, oblivious to the culture, he put his LEFT hand into my container. The words that were swimming around my head were enough to break my fast.

I thought that was the perfect time to pray, so I found a quiet spot — or so I thought. Halfway through my sujood (prostration) someone barged in. “Mate, did you drop something?” He sounded genuinely concerned. Just as I was doing the second sujood, I felt him going down on his hands and knees and he was scanning the floor for whatever he thought I was looking for. When I didn’t respond — because, you know, I was mid-prayer — he got even more confused and started staring at me. I finished, stood up. “Did you find it?” he asked. “Yeah,” I said, “I found my sanity.”

It was late by the time I was finally on stage. I was tired, grubby and feeling about as funny as yeast infection in spandex. I had to dig deep to find the energy. And then came the hecklers. Not any old hecklers, stag do hecklers. Urgh. Normally, I’d have been ready to verbally obliterate them, but it was Ramadan. Which meant I had to respond with kindness. Do you know how hard it is to be nice to a heckler? It’s like watching a comedian perform a joke they stole from you and being forced to laugh.

Somehow, I got through the set and, most importantly, I didn’t break my fast with rage. My first Ramadan as a comedian made me realise that being a Muslim comedian can be the ultimate test of patience and resilience — especially during the holy month. And next time? I’ll eat my food in my car.

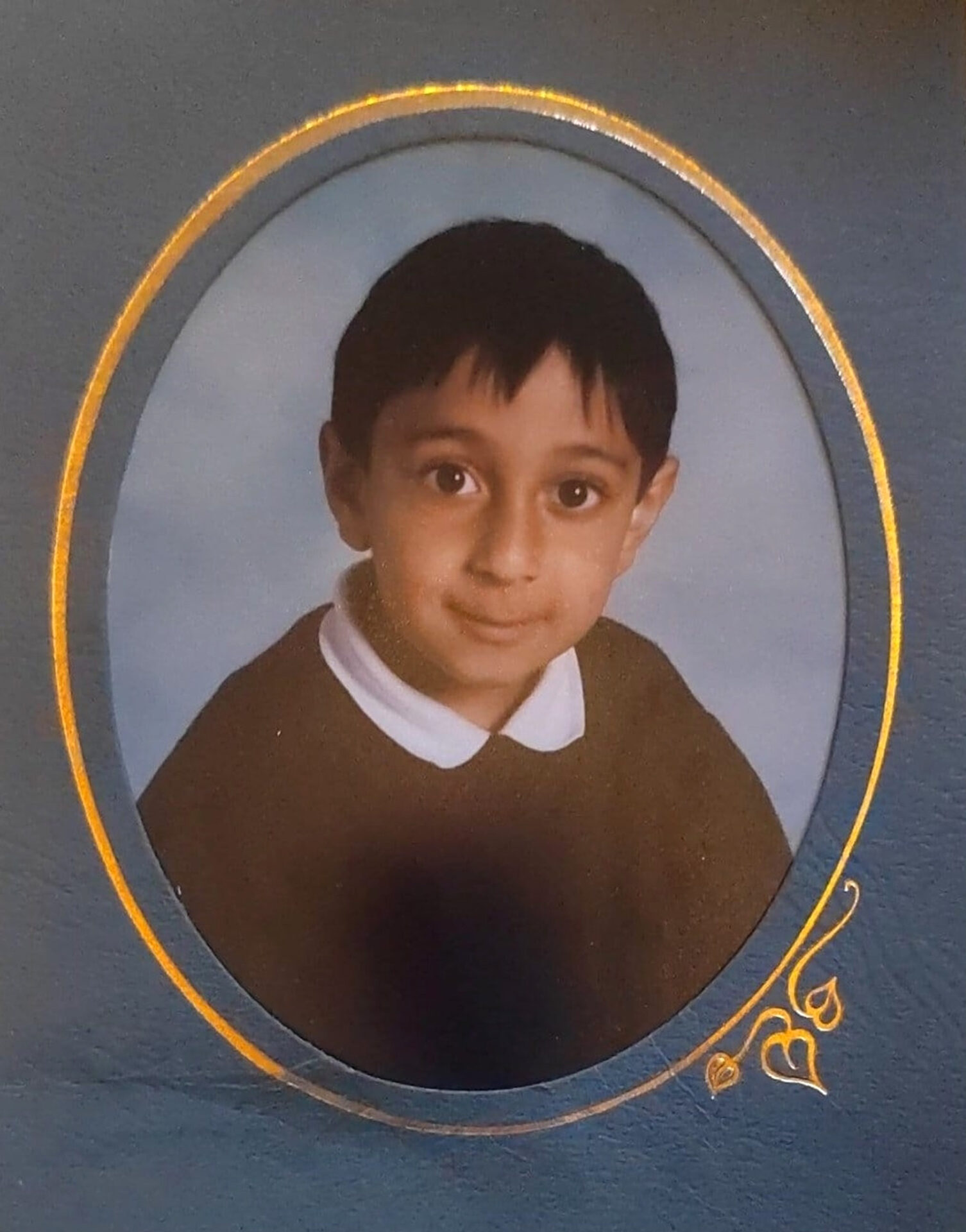

Bilal Zafar — ‘I swallowed a bite of cupcake and was hit with instant regret’

My brothers are nine and seven years older than me, so as a child, mashing the buttons on an unplugged video game controller as they played Mortal Kombat was the closest way I could feel included. When Ramadan came around, my family would fast and my mother would say that I could join in with a half-day fast if I wanted.

That would usually last for about an hour until I wanted a cheese string, but it felt amazing to be taking part — and I was excited about the deep-fried food and Rubicon mango juice we only ever had during Ramadan. Having family and friends over for iftar and breaking my fast with them always felt like a magical occasion, even if I had been snacking and drinking squash all day.

In 2000, I was eight years old and Ramadan fell in November, meaning that the days were very short. Sunrise was around the time I was leaving for school and sunset wasn’t long after classes ended, so I was confident I would be able to fast properly for the first time.

The first few days were pretty easy. It was great. I was basically just having to miss lunch and then break my fast shortly after getting home. There was a feeling of admiration and intrigue from my classmates and teacher, different from how I’ve often had looks of confusion over fasting from non-Muslim peers as an adult. I was delighted and proud to be taking part.

I was getting into the rhythm and routine of Ramadan, trying to make sure I could fast for the full month, be on my best behaviour and pray regularly.

I got so relaxed that one day, about halfway through the month, I somehow managed to forget that I was fasting. That’s when it happened. One of my best friend’s mum brought some cupcakes into school for his birthday. Unfortunately, eating cake is second nature to me and I gladly had a big bite.

I swallowed and was hit with an instant feeling of regret. A harrowing, panicky emotion like if you’ve dropped your phone in the bath. I kept quiet. It was as if I had committed a crime and had to keep my head down.

I got home not knowing what to do. Of course, my mum could tell that something was up, like she always can. I was almost in tears as I confessed the terrible thing that I had done. She looked at me, called my dad into the room so that I could tell him as well. My mum hugged me as they both tried to control their laughter. It was a good thing my brothers weren’t around because I would have had some seriously cruel sibling teasing.

My parents explained that eating a bit of a cupcake by accident was absolutely fine, because the only thing really mattered was my intention. I had heard about this before, but that was the first time I truly understood it.

That notion of intention has stayed with me throughout my life as it reminds me to have perspective when I make mistakes, to see the bigger picture and not stress too much about minor issues.

And when I’m not fasting, I will still gladly accept any cake on offer.

Shazia Mirza — ‘If I ever get the opportunity to go to Mecca again, I will make the most of it’

In Islam, Allah invites people to perform the Hajj and Umrah pilgrimages. It is said that you don’t just arrive in Mecca, you have to be invited. If your name’s not on the list, you’re not coming in.

I got my first invite when I was about 20. I was with my dad, had no idea what I was doing, so just followed his lead. At that time in my life, I wasn’t driven to Mecca by a forceful spiritual need. These first Umrahs were more of an experience I was witnessing, rather than something I was experiencing myself.

I didn’t end up going again for about 25 years. Not because I didn’t want to, but because I never had the chance — I wasn’t invited.

But last year, my dad wasn’t well. At 85, he was old and frail and both my sister and I felt that time was limited. We managed to get to Mecca in the last ashra of Ramadan, the final 10 days. These are special, as it says in the hadith: “Umrah in Ramadan, he attains the reward of doing a complete Hajj with the Prophet (peace be upon him)”.

Presented with my invite from Allah, my reason for being there had greater meaning. My deen had progressed and I felt closer to Allah. I was with my dad and we were praying for the same cause: the afterlife; that when he passes away, we will all meet again.

But it was hard. I got really ill, I was trodden on, pushed around, hit by a wheelchair in the back of my leg. It was boiling hot, crowded and I was fasting at the same time, so I couldn’t drink water. We did it, though. My dad in a wheelchair and my sister and I walking alongside him barefoot.

In Mecca, you see people’s commitment to their faith. You see people getting up in the early hours for tahajjud, suhoor, standing on the streets praying taraweeh for hours. Witnessing that selflessness had a profound effect. I remember my sister saying to me: “We need to do as many Umrahs as possible, because we don’t know if we will ever get invited here again.”

We did four Umrahs in total on that trip, two of them with my dad. And I’m so glad we did, as six months later he became so ill he was unable to travel again.

It’s hard to describe a spiritual experience because a lot of it is felt — often faith can’t be explained. Now I know if I ever get the opportunity to go to Mecca again, I will make the most of it. No matter how tired I am, I will spend every minute doing some kind of worship, as I never know when I’ll be invited back.

There are certain things in life that you wait for, wish for, but they never seem to happen when you want them to. But you have to trust the timing. Sometimes that invitation comes your way just when you need it to.

Newsletter

Newsletter